The Paper Brigade: Rescuing cultural artifacts during and after WWII

The horrors of the Holocaust were met with various forms of resistance. Some insurgents fought back by smuggling food and weapons into Jewish ghettos. Tonight, we'll tell you about a very different kind of resistance group nicknamed the Paper Brigade. Made up mostly of writers and intellectuals living in what is now Vilnius, Lithuania's capital, the members risked death, smuggling artwork, books and rare manuscripts - hiding them in underground bunkers. Today, 80 years after the Paper Brigade fought back against cultural genocide —their heroics are still unfolding. There's an active search-and-rescue mission underway in Vilnius, where troves of hidden material continue to be uncovered, discovered and recovered.

Jonathan Brent: My intention is not to seize it and take it and bring it someplace. It's to open it up so the public can see it

Jon Wertheim: Put it out there.

Jonathan Brent: And put it out there in the world.

Jonathan Brent is the executive director of YIVO, an institute based in New York which houses 24 million Jewish cultural artifacts.

This past spring, we met him in Vilnius, where the YIVO Institute originated in 1925 and where some of its collection has been unaccounted for since World War II. We looked on as Brent examined documents in a storage closet at Lithuania's national library.

Jon Wertheim: This is very much an active investigation.

Jonathan Brent: Yes, this history is not over.

Beneath the hill of three crosses, Vilnius wears its history with grace. But its beauty masks a dark chapter. Today the city is mostly Catholic, but before the second world war Vilnius was almost half Jewish – and a magnet for artists, musicians, poets and dramatists from all over Eastern Europe. They wrote, mostly in Yiddish, the German-Hebrew dialect of Eastern European Jews.

Jonathan Brent: Most people in America know nothing of the great flourishing of Jewish culture that took place in this city.

Then in the summer of 1941, the Germans invaded the Soviet Union and occupied Lithuania. Many of the local citizens collaborated with the Nazis and within six months, 50,000 of the 70,000 Vilnius Jews were killed.

Jonathan Brent: One of the worst slaughters during the Holocaust. Some 90% to 95% of the Jewish population of Lithuania was murdered brutally, cruelly, sadistically.

Jon Wertheim: Not often in [the] camps I gather?

Jonathan Brent: Shot burned. Hideous.

The Nazis were also determined to extinguish the Jewish culture. And, in Vilnius, there was no place more central to Jewish culture than YIVO, the Yiddish Scientific Institute, a Smithsonian of sorts, part museum, part library, part university. Its archive was as varied as it was massive. Sigmund Freud and Albert Einstein sat on YIVO's original board; Marc Chagall, who painted Vilnius' synagogues, opened its art wing.

Jon Wertheim: It strikes me someone had an unhappily prescient sense of all this, that you're creating this collection and capturing this history right before other people are

Jonathan Brent: Wipe it out, yes.

Jon Wertheim: Trying to erase it--

Jonathan Brent: Well, the Jews have had-- quite a bit of history that prepared them for that eventuality.

After the Germans' invaded Vilnius, a special squad of Nazis commandeered YIVO's headquarters with designs of looting the art and rare books and burning everything else. But the Nazis needed help assessing what was valuable, so they rounded up 40 Jewish writers and artists mockingly nicknamed the Paper Brigade to sort through rooms upon rooms housing YIVO's collection. But the Paper Brigade had other ideas. They set aside the most significant manuscripts and art, including a sketch by Picasso, and organized a smuggling operation back to the ghetto. Homemade diapers sewn into their pants concealed the contraband from the Nazi guards. They had ten hiding places, the largest was underneath a house, 60 feet down and accessible only through a sewage tunnel.

Jon Wertheim: you've said that some people resisted by taking up arms, or by smuggling food or medical supplies. And this was a form of resistance also?

Hadas Kalderon: Yes, because they knew that if they are not going to survive the Jewish people would have their culture again to remember.

Hadas Kalderon is the granddaughter of Avrom Sutzkever, an avant garde poet in Vilnius in the 1930s. During the war, he became one of the leaders of the Paper Brigade.

Hadas Kalderon: It was a nickname, the Paper Brigade. people in the ghetto laughed at them. "Oh, you're smuggling papers? Smuggle food. We need food."

Jon Wertheim: What was the response to that?

Hadas Kalderon: You have to understand that poetry, literature, and culture was part of their soul.

Kalderon grew up listening to her grandfather's war stories, so we invited her to meet us in Vilnius from her home in Israel. We retraced Suztkever's smuggling route and she told us about the night her grandfather barely escaped the Nazi guard at the gate of the Jewish ghetto.

Hadas Kalderon: He was knocked down. And the papers came out of him. And he took the gun, the guard, and said, "what you're not allowed to take anything in-- anything."

He says he told the guard that the papers were needed for kindling.

Hadas Kalderon: And he let him in.

Among the items Sutzkever concealed, the original writings of Sholem Alecheim, known as the Mark Twain of Eastern Europe, whose stories inspired "Fiddler on the Roof."

In 1944, the Soviets liberated Lithuania and reclaimed the country as part of the Soviet Union. Only eight of the 40 members of the Paper Brigade had survived the war.

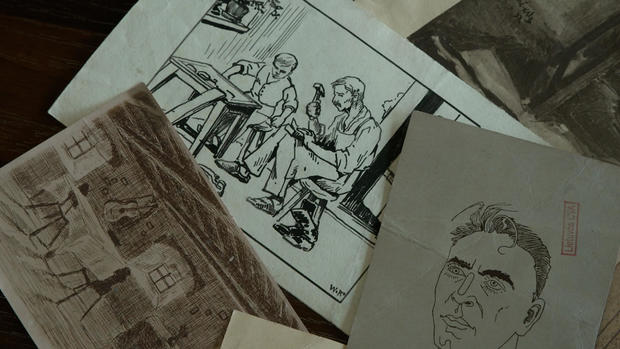

Hadas Kalderon: This is an unbelievable picture of them coming back to see what can be saved.

Armed with a homemade wheelbarrow and shovels, they dug up the treasures from their hiding places.

Jon Wertheim: Your grandfather put himself at huge risk doing this. Did he ever discuss with you whether it was worth it or not?

Hadas Kalderon: he felt that if he survived than he has a mission to be the deliverer for the dead, for the stories, for the cultural. So that is the point of living.

But with the Soviets now controlling Lithuania, Jewish life again came under assault. Everything the Paper Brigade risked their lives to protect was endangered for a second time.

Jonathan Brent: These treasures that connected you today with a past of 700 years ago gave you a sense of your own history and the value of it and importance of it. And the Soviets wanted desperately to destroy that and make you a Soviet citizen.

Jon Wertheim: Another form of erasure.

Jonathan Brent: Yes, absolutely

Avrom Sutzkever and others began a 2nd secret operation. They stuffed their suitcases with books and enlisted couriers, redirecting materials to YIVO in New York City, where the institute had relocated during the war. The rest of the material was assumed destroyed. But Antanas Ulpis, a brave Catholic librarian, took up the cause in Vilnius. Risking his own life, Ulpis hid whatever was left behind in this empty Catholic church.

But for almost 50 years, remnants of vilnius' Jewish life vanished. And the city's Jewish past was not discussed.

Vilnius University Professor Mindaugas Kvietkauskas grew up Catholic and would become Lithuanian's minister of culture.

Mindaugas Kvietkauskas: My knowledge about Jewish history and culture and the Holocaust was very vague when I was a teenager.

Jon Wertheim: you weren't taught about the Holocaust in school.

Mindaugas Kvietkauskas: No. No. I had to discover this legacy by myself.

He was 17 when he finally chanced upon faded Yiddish inscriptions in the old section of town. As his curiosity grew, he studied Yiddish and says he became intoxicated by the culture that it encompassed.

Mindaugas Kvietkauskas: Yiddish literature for me is this nexus of poetry, of beauty, and human destinies. It is full of voices of survivors, of victims, and also of heroes who tried to rescue this culture, this community against the evil of totalitarianism.

Kvietkauskas heard whispers in Vilnius about a hidden literary bounty, but it wasn't until the breakup of the Soviet Union in the early 90s that Jewish culture could emerge from hiding. Kvietkauskas was invited inside the 18th century Catholic Church, where Ulpis, the brave librarian, had hidden the books. Through the years, Ulpis had created a book sanctuary, with literary works rescued and concealed from the Red Army, floor to ceiling under the dusty baroque arches. The church is now empty and awaiting renovation. But we asked Kvietkauskas to take us there.

And show us where the books were hidden - underground, in the confessional. Even in the bellows of the 18th-century organ.

Jon Wertheim: I'm just trying to picture you walking into this unexplored Book Palace.

Mindaugas Kvietkauskas: Some of those books had blood stains, some of them had inscriptions made by the readers who most probably were killed.

Today, these books are slowly bringing legacy back to life so says Jonathan Brent, who became YIVO's director in 2009.

Jonathan Brent: The materials that YIVO had collected represented a body of materials which if it were wiped out would leave an absence that could never be filled in. And it would lead to total cultural deprivation for those Jews who might survive.

The literary equivalent of Easter eggs, the rescued artifacts keep popping up in Lithuania. It's all triggered a familiar custody battle. The Lithuanians argued for the trove to stay in Lithuania, YIVO's executives insisted the material be reunited with its collection in New York, fearing the documents would continue to deteriorate, Brent brokered a deal, YIVO would fund the preservation now and iron out ownership details later.

Stefanie Halpern: These are fragments of books that were scooped out of the burnt rubble of the YIVO building brought here to New York preserved in these boxes.

YIVO's director of archives in New York, Stefanie Halpern, just completed a seven-year, $7 million project overseeing the cataloging and digitizing of the Paper Brigade's entire collection.

Jon Wertheim: Do we know if the Paper Brigade preserved this?

Stefanie Halpern: They did.

Stefanie Halpern: And these are the surviving pages. It's not the full manuscript that we have. Only about a dozen or so pages.

As new works are discovered voices from a century ago are amplified. Consider the works of Avrom Sutzkever, who now, years after his death, is coming to be appreciated as a towering 20th century poet. His 1946 memoir was published in English just last year.

Hadas Kalderon: They are learning Sutzkever in many, many universities, not just in Lithuania, also in the United States, and in Canada, and in China, and in Japan.

Lithuania is now home to only 4,000 Jews. But it's on account of the Paper Brigade and continuing discoveries, that the country is starting to reckon with the Nazi atrocities and its uncomfortable history. Even schools are now starting to teach about how Lithuania's Jews died—and how they lived.

Jon Wertheim: Do you know the phrase CPR? Strikes me you're really bringing it back to life.

Mindaugas Kvietkauskas: I hope so. But we still-- lack wider recognition in our-- in-- in our society. In the course of last 20 years. [The] mentality of our society became more open towards different versions of its own past.

And in the process, Lithuanians have started learning about how, an unlikely group of resistance fighters both Jewish and Catholic took the ultimate risk to assure arts and letters would survive.

Produced by Julie Holstein. Broadcast associate, Elizabeth Germino. Edited by Stephanie Palewski Brumbach.