Appeal in Palin's defamation case unlikely to erode press protections, legal experts say

Washington — Former Alaska Governor Sarah Palin's as-yet unsuccessful legal battle against the New York Times has breathed new life into the debate over whether courts should reconsider First Amendment protections for the press that have been in place for more than half a century.

And while a pair of conservative justices on the Supreme Court has indicated a willingness to revisit the landmark 1964 decision that set the bar for public figures to prove defamation by news outlets, legal experts believe Palin's case won't be the one that satisfies their charge.

"The broader significance of the Palin case has really been overrated generally. I think this is more of a one-off," said David Snyder, executive director of the First Amendment Coalition who represented Mother Jones in a defamation suit. "I don't think this is the beginning of the death knell for Times v. Sullivan, but because it's in New York City, because it's Sarah Palin, because it's the New York Times, it's gotten enormous attention."

Palin brought her 2017 case against the Times in federal court in response to an editorial the paper ran that incorrectly tied her campaign rhetoric to a 2011 mass shooting in Arizona that left Congresswoman Gabby Giffords severely wounded and six dead.

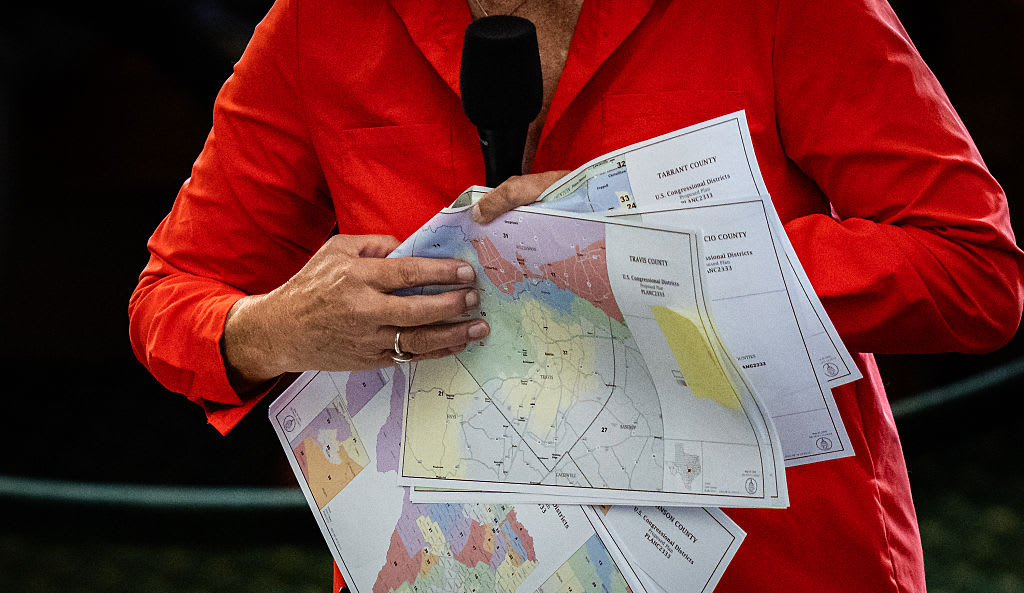

The paper issued a correction after the editorial was published, stating it had "incorrectly stated that a link existed between political rhetoric and the 2011 shooting" and "incorrectly described" a map of electoral districts circulated by Palin's political action committee that superimposed the image of crosshairs over several Democratic districts, including Giffords'.

Palin alleged in her suit that the Times libeled her with the editorial about gun control.

Following a trial in federal court, a jury on Tuesday rejected Palin's claim against the New York Times, one day after the judge presiding over the lawsuit said he would dismiss the case if the jury ruled in her favor because the former Alaska governor failed to show the paper acted with actual malice, the legal standard she was required to meet to prove defamation.

U.S. District Judge Jed Rakoff revealed Wednesday that jurors knew before rendering their verdict that he would rule in favor of the Times, as several received news alerts to their phones about the Monday announcement of his decision. But he wrote in a brief order that the jurors "repeatedly assured" his law clerk the notifications did not play any role in their deliberations.

Regardless, the former governor and Republican nominee for vice president is likely to appeal the decision to the 2nd U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals and possibly ask the Supreme Court to wade in if she is unsuccessful at the appellate level.

Palin's case has reinvigorated discussions over the legal protections for news organizations that have been in place since the Supreme Court's 1964 decision in New York Times Co. v. Sullivan. But for those pushing for the court to revisit the nearly 60-year-old precedent, Palin's case may not the ideal vehicle for doing so.

For one, courts are generally reluctant to wade in when there has been a decision by a jury, and the case involves a New York state law, Snyder said. Palin also is hardly an obscure figure, having served as governor of Alaska and the Republican candidate for vice president in 2008.

"If there is a plaintiff who has a real longshot in a case like this, Sarah Palin is it," Snyder said. "Everyone knows who she is. She's not only a household name like Tom Cruise and LeBron James, but she was an elected official and in some ways, that's an even higher bar for a plaintiff. She's the front of the line for folks who have a difficult time meeting the actual malice standard as a plaintiff in a defamation case."

Under the legal standard established for libel cases set by the Sullivan decision, a public figure must prove the offending statement was made with actual malice, meaning the publisher knew it was false or acted with reckless disregard of whether it was false.

Lyrissa Lidsky, dean of the University of Missouri Law School and an expert on defamation law, said in their decision in the Sullivan case, the justices recognized errors are "inevitable" in the news business, and while proving actual malice is difficult, it's not impossible.

"If you want to use defamation law to send a message about the irresponsibility of media actors and the bias of media actors, Sarah Palin got a lot of traction in that regard," she said. "If you want to use a defamation law case to win a judgment as a public figure against the media, it is hard to say we've proved actual malice, especially against an organization with processes in place to get it right."

For the Times, Lidsky said the case dealt a "reputational blow" to the paper and signaled to other news outlets that "you've got to set high standards and hold yourselves to that high standard."

Palin's legal battle with the Times is rare in that it went to trial. Many defamation cases are settled or dismissed in early stages, given the high bar a plaintiff must meet to succeed.

But two Supreme Court justices have in recent years suggested the standard set by Sullivan has left many people without a remedy for defamation and called for the court to reconsider the landmark ruling, shaking what legal experts believed was the firm foundation on which the decision rested.

"New York Times and the court's decisions extending it were policy-driven decisions masquerading as constitutional law," Justice Clarence Thomas wrote in a 2019 opinion, adding: "If the Constitution does not require public figures to satisfy an actual-malice standard in state-law defamation suits, then neither should we."

Justice Neil Gorsuch, meanwhile, wrote last year that the media landscape has changed dramatically since 1964 with the growth of the internet, and questioned "how well these modern developments serve Sullivan's original purposes."

"Rules intended to ensure a robust debate over actions taken by high public officials carrying out the public's business increasingly seem to leave even ordinary Americans without recourse for grievous defamation," he wrote. "At least as they are applied today, it's far from obvious whether Sullivan's rules do more to encourage people of dissenting goodwill to engage in democratic self-governance or discourage them from risking even the slightest step toward public life."

It takes four votes for the Supreme Court to agree to hear a case, and Lidsky said she doesn't believe there is a "straight line from criticisms [of Sullivan] to it's gone tomorrow." Still, she said it's "a really shocking thing to say the foundational case of modern First Amendment law should be overturned."

"Are they going to carve away at the edges? Maybe," she said of how far the court could go in a future defamation case.

The justices, Lidsky continued, could reconsider the definition of a public figure under current law, which has been broadened by lower courts over time.

"One half-step correction is to take another case and say, 'No, we meant it when we defined the public figure category narrowly,'" Lidsky said. "That would be a way to really change the playing field a little bit without being accused of judicial activism and without doing anything really shocking."

Snyder suggested that with their scrutiny of the Sullivan decision, Thomas and Gorsuch are attempting to establish skepticism of the actual malice standard to lay the foundation for modifications at the margins of the case law that has developed.

When it comes to Palin's suit against the Times, though, he said, "if there is an impetus at the court to address the actual malice standard in some way, whether to modify it or what have you, would this case be the best way to do that? I don't think so."