Opioid overdoses spike 30 percent, hospitals report

A new report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention brings more bad news for the nation's continued fight against the opioid epidemic. Data from hospital emergency departments show a big increase in drug overdoses across the country.

In a press briefing on Tuesday, CDC Acting Director Anne Schuchat, M.D., said the U.S. is seeing the highest drug overdose death rate ever recorded in the country.

According to the study, which examined data from 16 states, emergency department visits for suspected opioid overdoses jumped 30 percent from July 2016 through September 2017.

Opioid overdoses increased for both men and women, across all age groups, and in all regions, though there was some variation by state, with rural and urban differences.

"Long before we receive data from death certificates, emergency department data can point to alarming increases in opioid overdoses," Schuchat said in a statement. "This fast-moving epidemic affects both men and women, and people of every age. It does not respect state or county lines and is still increasing in every region in the United States."

The Midwest saw the biggest jump in opioid overdoses, with a 70 percent increase from July 2016 through September 2017.

Certain areas in the Northeast were also hit particularly hard, with Delaware experiencing a 105 percent increase and Pennsylvania an 81 percent increase in opioid overdoses during that time.

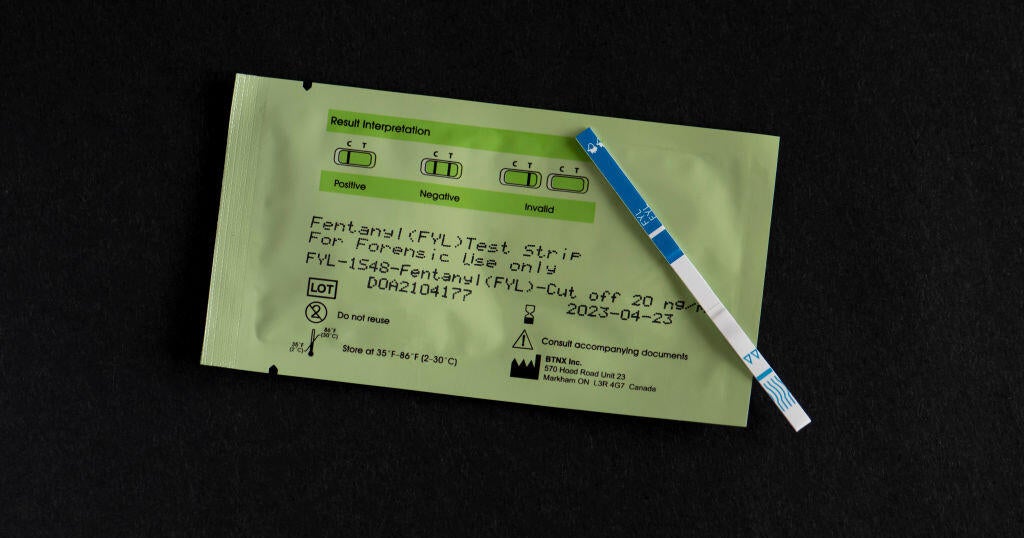

The reasons for these increases are unclear, but officials say it may have to do with changes in the drug supply, including the availability of newer, highly toxic illegal opioids such as fentanyl, which has been spreading rapidly in recent years. Fentanyl, a synthetic drug that's 50 to 100 times stronger than morphine, is often mixed in to make heroin more potent, contributing to many ODs.

"It may not be that more people are using, but in fact that a single use of a more deadly drug is what we're seeing," CBS News medical contributor Dr. Tara Narula said on "CBS This Morning."

Though the report was overall a somber reminder of the devastating effects of opioid addiction, there were a few hopeful findings.

In Kentucky, a state hit hard by the opioid epidemic, emergency department visits for opioid overdoses actually decreased by 15 percent over the study period. In Massachusetts, New Hampshire, and Rhode Island, there were also small decreases of less than 10 percent.

Schuchat said she is cautiously optimistic that strategies implemented in these states to combat opioid addiction may be working.

Officials say looking at emergency room data can help responders gather important information before an overdose turns deadly, including where the person was coming from and what day of the week and time of day the overdose occurred. This can make it easier to identify where there are gaps in local resources and how they can best be allocated, since having one overdose makes it likely a person will have another.

The report also calls for state and local health departments, as well as emergency departments, community organizations and individuals to come together to lessen the impact of the opioid epidemic.

These steps include:

- Increasing distribution of naloxone, an overdose-reversing drug also known as Narcan, to first responders, family and friends, and other community members in affected areas, as policies permit.

- Increasing availability of and access to treatment services for opioid users, including mental health services and medication-assisted treatment like methadone clinics.

- Supporting programs that reduce harms that can occur when injecting opioids, including programs that offer screening for HIV and hepatitis B and C, in combination with referral to treatment.

- Promoting opioid prevention and treatment education.

- Storing prescription opioids in a secure place, out of reach of others, including children, family, friends, and visitors, and properly disposing of them when no longer needed