Money, dinners and strip clubs: How pharmaceutical executives bribed doctors to prescribe dangerous fentanyl drugs

Nearly 70,000 Americans die each year from drug overdoses, mostly from opioids. As 60 Minutes has reported, the explosion in both the demand and supply of pharmaceutical opioids began with the aggressive marketing of narcotics to treat chronic pain. Now, we reveal the story of the powerfully addictive, fast-acting opioid, fentanyl. Our year-long investigation, which concluded just as the coronavirus was spreading, uncovered the playbook of sales practices that triggered an explosion of prescriptions. We will introduce you to two insiders on different sides of the law: a top opioid salesman whose rise and fall spanned the epidemic, but first federal agent Greg Tremaglio, who in 2003 saw the crisis coming and tried to stop it.

- The opioid epidemic: Who is to blame?

- Alec Burlakoff: The rise and fall of a pharmaceutical opioid sales executive

Greg Tremaglio: If you're gonna intentionally, knowingly break the law your profits have to be so significant that when the FDA comes knocking and they hit you with the $425 million penalty, you're still smiling. You're sad in front of them, but when you walk out the door, you're smiling. You're smiling because you just made a billion dollars worth of profit. And it's worth it to them. It's worth it.

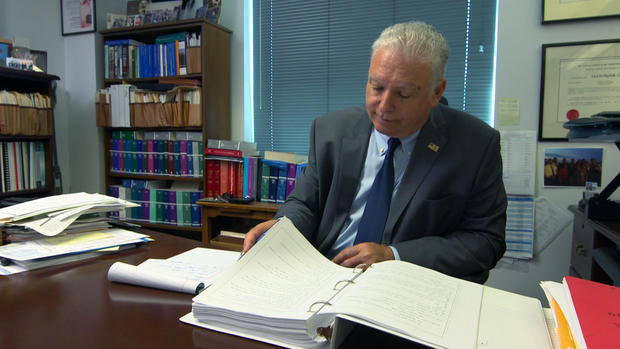

When Greg Tremaglio looks back at the carnage caused by the rise in the use and abuse of opioids, one early case sticks in his mind. In 2003, he was the senior special agent assigned to the undercover arm of the Food and Drug Administration's D.C. Office of Criminal Investigations. His target: Cephalon, one of several drug companies doing business in ways that brazenly flouted FDA regulations.

Bill Whitaker: They weren't afraid of the FDA.

Greg Tremaglio: Why would they be? Back then, you only received a misdemeanor. Nobody was prosecuted.

Bill Whitaker: So they're willing to take that slap on the wrist because the benefits are so great.

Greg Tremaglio: Yes.

Bill Whitaker: Profits are too big.

Greg Tremaglio: Way too big.

At the time, when a drug company was caught violating FDA regulations, federal prosecutors, typically, would negotiate corporate settlement agreements without holding individual pharmaceutical executives accountable. But agent Greg Tremaglio hoped this time would be different. His investigation revealed Cephalon was violating strict FDA laws on drug promotion with three drugs, including a synthetic opioid, Actiq – a dangerous, fast acting fentanyl sold in lollipop form, for easy absorption through the mouth. The drug is 100 times more powerful than morphine, intended for severe cancer pain only…

Greg Tremaglio: These drugs are so powerful that they received approval by FDA for their indicated use, which was strictly for cancer patients with severe pain that have a tolerance level to other opioids. So morphine's not working for them anymore, and they're in-- still in severe pain. And they need something that's gonna give 'em a recovery immediately. That's what this lollipop is.

Bill Whitaker: For people in end stage cancer.

Greg Tremaglio: Yes.

Bill Whitaker: A doctor can prescribe things off-label. So what was wrong with what they were doing?

Greg Tremaglio: Yeah, in the-- in the FDA we call that the "practice of medicine." We give medical doctors the ability to prescribe whatever they think's gonna help treat their patients. But that's with the understanding that the medical doctor is getting presented with accurate, factual information from the drug sales rep. They are not being groomed to promote drugs off-label.

The FDA approved labeling for Cephalon's fentanyl drug Actiq, also called the package insert, tells doctors and patients who should take Actiq and how it should be used.

The document carries the weight of a legally binding agreement between the FDA and drug companies, limiting how sales reps can promote a drug. Pushing a drug for patient groups not listed on the label, spreading misleading information, or publicizing a potentially deadly drug as less dangerous than FDA evaluations indicate, is called off-label promotion. And it's against the law.

Greg Tremaglio: Profit over patient health, we call it. Doesn't matter what the drug's indicated use is. If I'm a sales rep I'm hustlin' it. I'm slingin' it as fast as I can.

Bill Whitaker: If not for cancer, what else would they be pushing this drug to be used for?

Greg Tremaglio: Pain is pain. That's their motto. So whether you have a migraine, pop a fentanyl lollipop. Whether you have a back injury, take a fentanyl lollipop. It didn't matter.

Alec Burlakoff was a star sales representative at Cephalon. He told us he would say almost anything to convince doctors to prescribe Actiq, on or off-label. Before joining Cephalon, he was a stand-out sales rep at Eli Lilly and Johnson & Johnson. Wherever he worked, he says, the sales tactics were the same: ignore the FDA's "off-label promotion" laws.

Alec Burlakoff: I was taught to forget the patient. To not think about the patient. Take the human aspect out of it. It's like selling widgets.

Bill Whitaker: Were you not aware of what these opioids were doing to communities around the country?

Alec Burlakoff: What is your job? What is your title? Sales. Sell. Do you understand?" Either understand or-- or pack your bags.

Bill Whitaker: What's the key to being a successful salesman in the pharmaceutical, especially the opioid end of the business?

Alec Burlakoff: The key to success? The less of a conscience you had, the better.

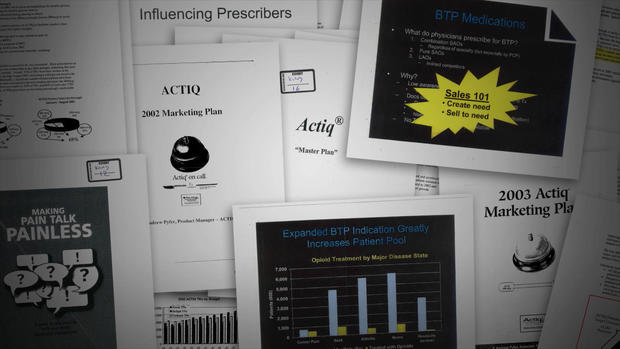

60 Minutes went to court in Oklahoma to get Cephalon's internal documents unsealed: the drug maker's "master plan" for promoting its powerful drug, Actiq. A virtual "how-to" for breaking federal law. The documents reveal Cephalon's strategy was to broaden the use of the opioid beyond cancer patients with severe pain to the general pain market. Including "but not limited to osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, chronic back pain, migraine headaches..." Getting doctors to prescribe the drug off label was, "the most critical component of the actiq tactical plan…"

Alec Burlakoff: They push you right to the line, and if you go to that line every single day, what happens? Eventually you start to cross the line. And they want you to cross that line.

Bill Whitaker: I guess you would have to run through the risks of abuse when you're talking to the doctors about the drugs. But with a wink and a nod?

Alec Burlakoff: Not even. If you go through training like me as a young man, you drink the Kool-Aid. You drink it like a fire hose. And I'll never forget. You can go as high as you want, as long as they're still in pain.

The federal investigation of Cephalon began in January 2003, when a sales rep with a troubled conscience got in touch with Greg Tremaglio, telling him Cephalon was pushing its sales team to break the law. To gather hard evidence, agent Tremaglio got approval from federal prosecutors to wire up the sales rep and conduct a surveillance operation of company employees at this Nevada hotel, site of the drug maker's annual sales conference and training sessions.

Greg Tremaglio: We set it up right outta the hotel room where we managed the source as we wired him up and we sent him in, and we listened to the group conversations.

Bill Whitaker: You were listening in...

Greg Tremaglio: We were listening to the techniques of how to train somebody to sell drugs. And they're being encouraged by senior drug reps, "I like the way you steered the doctor away from the label, and you talked about severe migraine sufferers."

Bill Whitaker: How to groom a doctor...

Greg Tremaglio: Yes.

Bill Whitaker: What is your reaction to what you're hearing?

Greg Tremaglio: I was disgusted. It was just so open, the conversations, about disregarding the label and breaking the law. It's almost like a game to a lot of the sales reps. How many doctors do I have under my control, and how many prescriptions, or what we call scripts, how many are they issuing every single week?

Agent Tramaglio recorded days of damning conversations between sales reps providing accounts of their strategies. It sounded to him more like the corrupt tactics of an organized criminal operation.

Greg Tremaglio: They targeted what we call pill mill doctors first.

Bill Whitaker: Do they go visit the doctor, to see if he has a glint in his eye and see if he seems willing to play?

Greg Tremaglio: Starts there. It's-- it's a long process. You've got those that are established pill mills, what we call them, pain clinics that-- the doctors that just had no conscience. And then you had the ones that you're slowly grooming and developing in where they feel comfortable prescribing the drug off-label.

The internal Cephalon documents 60 Minutes obtained show just how Cephalon roped in willing or vulnerable physicians. It funded advocacy groups to promote opioids; spread deceptive information about addiction and offered incentives for doctors to prescribe opioids, including medical education programs, conference junkets, free dining and drinking and lucrative peer to peer speaking engagements. The "master plan" noted that quote "these programs generate immediate script impact," in other words, they got doctors to write more prescriptions.

Greg Tremaglio: And if they can't convince you, they have other doctors that they've already paid that they can reach out to

Bill Whitaker: "If you don't believe me, hey..."

Greg Tremaglio: "Talk to your peer." Except, they don't tell the doctor, "Oh, your peer has been to four vacation spots over the last year and we paid him approximately $200,000," or some astronomical consulting fee. It's garbage. It's no different than a bribe.

Bill Whitaker: No different from a bribe.

Greg Tremaglio: We're just calling it what it is. Instead of bribing doctors, we're calling it educational consulting, medical education program, fancy words. On the street they just call it something different.

Bill Whitaker: What do they call it on the street?

Greg Tremaglio: It's just a straight hustle. The only difference is they're in suit and ties when they do their hustle. That's the only difference.

When agent Tremaglio approached other sales reps at the 2003 Cephalon conference to cooperate as informants, word of the surveillance operation leaked out.

Bill Whitaker: After word got out that you were there--

Greg Tremaglio: All week--

Bill Whitaker: --listening in.

Greg Tremaglio: To their training.

Bill Whitaker: They scrambled.

Greg Tremaglio: Like cockroaches. Literally within 30 minutes there was probably 100 taxicabs out front. And we were sitting out our window watching the drug reps running out to get into the cabs to leave.

Bill Whitaker: So what happens?

Greg Tremaglio: Before I even got back to Washington D.C. My phone was already ringing...

It was a senior official in his FDA division, who was unaware of the extent of the operation, which was authorized by federal prosecutors. Greg Tremaglio told us the official objected to the aggressive investigative procedures. Agent Tremaglio was immediately pulled off the case.

Greg Tremaglio: My boss did not appreciate that. FDA did not appreciate that. That was a tactic that they were not comfortable with...

Bill Whitaker: Why was that?

Greg Tremaglio: Because, it's a white collar case. You can't treat 'em like a drug cartel.

Bill Whitaker: You should treat them differently?

Greg Tremaglio: With respect, because they're a legitimate pharmaceutical company.

Bill Whitaker: They're breaking the law. People are becoming addicted, dying from their practices. Why would the FDA, the government, wanna sort of tiptoe around them?

Greg Tremaglio: The FDA was afraid of the Big Pharmas.

Bill Whitaker: But you were providing them with the proof.

Greg Tremaglio: I had the proof.

Bill Whitaker: Were they duped? Or were they complicit?

Greg Tremaglio: I just think they stuck their head in the sand.

Bill Whitaker: What were you going for?

Greg Tremaglio: The Kingpin. The head of the snake.

Bill Whitaker: The executives at the top of Cephalon.

Greg Tremaglio: We never got that far.

The case ended in 2008, when Cephalon pleaded guilty to a misdemeanor for illegal promotion and paid $425 million in fines and settlements, less than a quarter of what Cephalon made in one year. The company was eventually sold for $6.8 billion. Alec Burlakoff found a new job at a company called Insys.

When Alec Burlakoff and former Cephalon sales reps found a new home in 2012 working for a pharmaceutical mogul named John Kapoor, they would rack up huge profits selling Subsys, a new formulation of fentanyl. Like Actiq, it was FDA-approved for cancer pain only. And on the strength of Subsys sales, Kapoor's company became a Wall Street sensation, one fueled by unbelievable greed and depravity. In the midst of the deadly epidemic, Insys sales reps got doctors to prescribe opioids for unapproved uses, enticing them with all-expenses-paid visits to strip clubs, fancy dinners and with money, which federal prosecutors say corrupted the practice of medicine. This time there would be no settlement. Insys was targeted as an organized criminal enterprise and its top executives were prosecuted.

In January, John Kapoor, billionaire entrepreneur and former CEO of Insys Therapeutics, arrived at a federal courthouse in Boston for sentencing.

A jury had found him, along with several of his top executives, guilty of racketeering, mail and wire fraud - conspiring to recklessly and illegally boost profits from the opioid painkiller Subsys, a fentanyl spray designed to be absorbed under the tongue.

Kapoor received five and a half years. His lieutenants received from 12 to 33 months, in part because of the testimony of the government's star witness: Alec Burlakoff, the senior vice president of sales at Insys, who had pled guilty and cooperated with prosecutors.

We talked with Alec Burlakoff, with the consent of federal prosecutors, before he was sentenced in January, but after he had testified about illegal sales tactics at Insys, including bribing physicians.

Bill Whitaker: The doctors, are they an easy mark?

Alec Burlakoff: No.

Bill Whitaker: Most doctors would throw you out?

Alec Burlakoff: Absolutely. And the faster you get thrown out, the better. Get thrown out and move onto the next guy. Keep going, keep going and eventually somebody is gonna stop and talk to you. And you start to wonder why. I'm a sales representative, I'm not a doctor. The doctor is looking at you, and he's saying to himself, what's in it for me? W-I-F-M. We call it the "WIFM."

Bill Whitaker: The WIFM.

Alec Burlakoff: WIFM. If they're saying, "What's in it for me."

Bill Whitaker: Then you know you've got one on the hook.

Alec Burlakoff: You got one on the hook. It doesn't mean you're gonna be successful. But you're gonna figure out real quick that the more you pay that doctor, the more he's gonna prescribe.

John Kapoor was a pharmaceutical industry success story. He immigrated to the United States from India and, as an executive and investor, made a fortune with a series of drug companies.

John Kapoor hired Alec Burlakoff after the salesman regaled him with stories from his days at Cephalon, bribing doctors, he said, paying them for speaking engagements.

Alec Burlakoff: He pounded the table, and he said, "That's our next VP of sales."

Kapoor asked him to start a similar speaker program at Insys.

Alec Burlakoff: I felt like I finally made it to the big leagues.

Bill Whitaker: And John Kapoor was asking you to do this?

Alec Burlakoff: Yes.

Alec Burlakoff: He wanted me to pay doctors to prescribe Subsys. I could do that. I've done it before, I can do it again.

Bill Whitaker: And you had talked about bribery?

Alec Burlakoff: Oh yeah.

Bill Whitaker: Used that word.

Alec Burlakoff: If I think that he's gonna be intimidated by the word bribery or that he hasn't been involved in that before on numerous occasions, I'm a fool.

Insys would pay some doctors – sales reps called them "whales" – as much as $125,000 a year in bribes, camouflaged as Insys "speaker program" fees.

All that money caught the attention of federal prosecutors in Boston, Nathaniel Yeager and David Lazarus.

Nathaniel Yeager: These doctors, these whales, were getting paid to speak 40, 50 times a year.

Bill Whitaker: So when you think about a speaker, you think of him going to, say, a ballroom. And you have other doctors there. And the speaker gets up and makes a speech about the benefits of this drug.

Nathaniel Yeager: Right.

Bill Whitaker: That's not what was going on--

Nathaniel Yeager: No, no.

What was going on, they say, was illegal, and the two prosecutors launched what would become the first criminal case to bring pharmaceutical executives to trial for fueling the opioid epidemic. They indicted seven Insys executives, including CEO John Kapoor and sales vice president Alec Burlakoff.

Nathaniel Yeager: It's just not something people that think about. But the reality is that doctors are licensed drug dealers. And the pharmaceutical companies know that.

At the heart of the indictment was the Insys speakers' program. And this is what it looked like, posted by one New York doctor on Instagram. "It isn't easy being me #friends."

Sales reps hired to recruit doctors for the speakers program didn't need to be experienced pharmaceutical salesmen, like Alec Burlakoff. But it did help if they had charm and sex appeal.

Nathaniel Yeager: They had people whose previous jobs were being a waitress at Hooters, people who worked at strip clubs… camp counselors…

Yeager and Lazarus called the speaker's program a sham.

Nathaniel Yeager: The doctor would just repeatedly invite her friends or his friends.

Bill Whitaker: Just, a night out paid by Insys.

Nathaniel Yeager: Right.

David Lazarus: Rack up a big bar bill. And then get a check in the mail for it.

Bill Whitaker: Was it-- was it that blatant?

Nathaniel Yeager: It was that blatant.

David Lazarus: The sales staff was taught to look for doctors who might be-- going through a rough time.

Nathaniel Yeager: And they would literally list what their strengths and weaknesses were.

And one of the things they would say is, "Divorced… needs money..."

Former senior vice president of sales Alec Burlakoff says the terms of the bribe were clearly spelled out to the doctor: increase the number and dose of prescriptions or the speaker spigot would be turned off.

Alec Burlakoff: "If you don't produce a return on investment of at least two to one via prescriptions of Subsys, not only will you disappear from the speaker's bureau, but your representative, will be gone as well."

Bill Whitaker: And you flat-out tell the doctor this?

Alec Burlakoff: Yes. One, the more you write, the more you're gonna earn. The more you increase the strength, the more you're gonna earn. And, doctor, if you don't like it, we walk away as friends. No big deal.

But in the case against John Kapoor, the R.O.I. - return on investment - was a big deal. Kapoor used real time data from an FDA patient safety program to track the doctors they were bribing, poring over patient dosages and prescriptions at the sales meeting held every morning, calling out his executives when they missed their targets.

Bill Whitaker: He's looking at the chart, and then he sees perhaps a doctor is not prescribing as much as he thinks he should be. How would he react?

Alec Burlakoff: Well, He would be irate. Within 24 hours that rep was demanded to be in that doctor's office and basically enforcing that they increase the dose.

Bill Whitaker: He was requiring you to push doses higher than the patient actually needed?

Alec Burlakoff: He made it mandatory that we launch what-- what he called an effective dose campaign.

Bill Whitaker: And what is that?

Alec Burlakoff: That's a fancy way of basically saying, let's make sure that the patient will come back and want more. Others might say, let's make sure we get the patients addicted.

Bill Whitaker: You're preying on these people--

Alec Burlakoff: Yeah, because they're desperate. They'll try anything. And they may get relief from Subsys initially, But we all know what's gonna happen. We know. We've been doin' this long enough. We know how it ends.

Bill Whitaker: And that is?

Alec Burlakoff: It ends in addiction, withdrawal, pain, suffering, and even death.

Bill Whitaker: And you didn't care about that?

Alec Burlakoff: Back then, I was numb to that.

Fred Wyshak: I was flabbergasted.

As the trial approached, Fred Wyshak joined the prosecution team to prepare the racketeering case. He pressured Alec Burlakoff to flip and testify against Kapoor. Best known for bringing down the Boston Mafia, and crime boss Whitey Bulger, Wyshak thought he had seen it all, until this: his first pharmaceutical case.

Bill Whitaker: And this is coming from a man who's gone after the mob.

Fred Wyshak: Yeah. (LAUGH) Yeah, I mean-- (SIGH) the mob does have, to some extent-- a code of conduct. And usually, they're only physically harming other bad guys. These people, they didn't care. Wasn't just bad guys who were getting hurt.

Bill Whitaker: And what was the impact this criminal activity was having on the consumers, the patients?

Fred Wyshak: Most of the patients who received this drug were noncancer patients taking Subsys-- essentially overmedicated them. It ruined their lives. Many of them lost their jobs, their families fell apart. Some were hallucinating. They all became addicted.

David Lazarus: Teeth falling out-- becoming zombie-like-- as a result of being given a medication this powerful, that you don't need.

Nathaniel Yeager: It was very compelling testimony. Some of them were shown insurance records that claimed that they had diagnoses that they've never had. And reacted to the fact that-- "I didn't have cancer. I didn't have that diagnosis."

Prosecutors called that insurance fraud. Insys CEO John Kapoor set up a scam to get insurance companies to pay for the drugs that were prescribed: he had Insys employees pose as doctor's office staff, to dupe the insurers.

Prosecutors obtained recordings of the calls and played them for the jury.

Recorded Phone Call:

-What medication are we speaking of today?

-This is for Subsys.

David Lazarus: So they're sitting in-- in a windowless room in Arizona, saying, "Oh, the weather's beautiful here, in Houston, today," or, "Oh, it's cold up here, in New York." They would outright lie. They would say the patient had cancer, when they didn't have cancer. And they knew. They kept track, at Insys, of what answers would work with individual insurance companies.

Insys executives prepared a script for call center workers that almost assured the insurance companies would pay.

Recorded Phone Call:

-And the patient's diagnosis?

-It's for the breakthrough pain. Yes.

-Malignant cancer pain?

-Yes ma'am.

David Lazarus: Nine times outta ten, that drug's getting approved.

Bill Whitaker: Wow. And-- and-- and this worked.

David Lazarus: It worked for years.

It helped make Insys so lucrative that when the company went public in 2013, it became the number one IPO in the country, worth more than a billion dollars. In court, prosecutors exposed a culture of greed. To make their case, they played for the jury an in-house company video, about titration, a medical technique used to increase a patient's dosage.

Fred Wyshak: I think the jury was disgusted when they saw that. I know I was disgusted.

Insys sales reps, rapping, boasting about doctors under their control, upping patients' dosage of subsys. In costume: the biggest dose -- 1600 micrograms. This was shown to a packed annual sales convention in Arizona in 2015. Ending with a cameo by Alec Burlakoff.

Bill Whitaker: Everybody laughed?

Alec Burlakoff: I'm sorry to say, everybody laughed, yes.

Bill Whitaker: The opioid crisis is raging outside the doors. And you're inside joking about it.

Alec Burlakoff: Yes. We were all, desensitized to what was going on.

On January 23, a federal judge sentenced Alec Burlakoff to 26 months and ordered him to turn over the $4.3 million he had made at the company. A dozen doctors were also convicted of crimes in connection with Insys. The company went bankrupt, and CEO John Kapoor is to report to federal prison in July to begin serving his sentence of five and half-years.

As for Wyshak and the federal prosecution team, this case launched a new tougher approach to corporate crime.

Fred Wyshak: I think sometimes white-collar criminals are more dangerous than violent criminals. And, more often than not, they get a kid glove treatment. And, I think that needs to stop.

Produced by Sam Hornblower. Associate producer, Emilio Almonte. Broadcast associate, Mabel Kabani. Edited by Matthew Danowski.