One way to help struggling workers: A guaranteed job

U.S. unemployment is at its lowest rate in half a century. But a large swath of working Americans still struggle to make ends meet. That's stirring interest in one idea to improve people's economic security: guaranteeing their access to jobs.

In recent months, several proposals have emerged for the federal government to guarantee people have access to jobs that pay a living wage for those laboring -- but not getting ahead -- in industries from retail to health care. New Jersey Democratic Senator Cory Booker filed legislation to test guaranteed jobs in 15 rural and urban areas cross the U.S. A report from the Center on Budget Priorities suggested job guarantees might give some regions facing an economic abyss a path back to better times. And a recent paper from the Aspen Institute proposes that "higher-wage" tax credits might encourage businesses to pay workers more.

Turns out the tens of millions of Americans who have jobs but live on the financial edge might be the most attracted to a job guarantee -- a phenomenon that has the potential to radically shift labor markets, according to a study from the Hamilton Project at Brookings Institution.

While the proposals vary, this sort of federal jobs program could include a subsidy in the form of tax breaks to local retailers to ensure that jobs exist, or it could be a government-paid job cleaning up a park or in construction, building roads and bridges.

Booker's proposal, for instance, "would guarantee that adults in participating communities who want to work can do so, in a job that pays a living wage and provides benefits like health insurance, paid sick leave, and paid family leave – all while helping to advance critical local and national priorities that are currently under-provided, like child and elder care, infrastructure, and community revitalization."

"Yes, the job market is booming in some ways, but it's not really booming for everybody," Jay C. Shambaugh, one of the Hamilton Project report's three authors and the Hamilton Project's director, told CBS MoneyWatch. "There is this question people have of what's the right way to approach that? Is there something more we can do -- or not -- that might make things work better?"

The authors avoided recommendations or calculating costs, which some studies peg at in the tens of billions, and instead concentrated on how such a policy might change the labor market. Here's what they found:

The underemployed may be most drawn

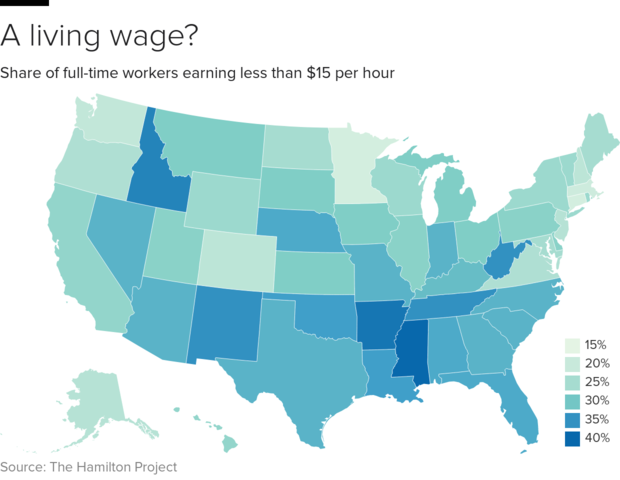

About 28 million people of what economists consider prime working age are employed full-time for less than $15 an hour, a level frequently cited by labor campaigns, state governments and even companies as a new minimum wage threshold. Another 5 million earn less than $10 an hour. All are potentially attracted to guaranteed employment.

And at least some of the 15.9 million part-time workers earning less than $15 per hour might switch to a guaranteed full-time job, the report said. That number is growing: part-time employees who want a full-time job rose to 4.8 million, up 423,000 since August, the Washington Post's Heather Long pointed out when the most recent federal figures were released Dec. 8.

At the same time, of the roughly 5.9 million currently unemployed, about one-third have been out of work for less than five weeks, the report noted, citing the Bureau of Labor Statistics. That raises the possibility they could be holding out for a job in their profession that pays more than $15 an hour.

Still others might stay away: More than half of people not in the workforce at all are caregivers, disabled or sick, and are unlikely to return.

Disenfranchised populations may benefit

Groups including African Americans, those in some depressed geographic areas, people with lower levels of education and women, including caretakers and working mothers, aren't getting the same bump as those lifted by a booming job market and may benefit most.

"At almost any moment in time, twice as many black Americans who wanted to work have been unable to find a job compared to whites," the researchers wrote. "Policies that encourage hiring might most benefit those groups that have been locked out of the labor market, and this is likely even more true of government hiring or guarantees."

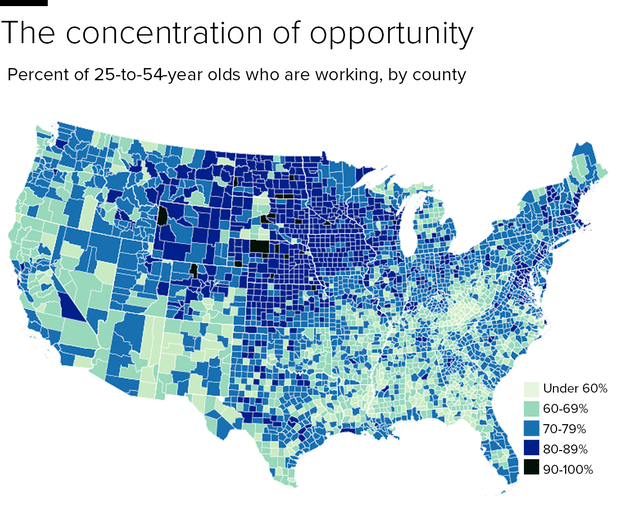

Some regions would see a bigger boost

One of the biggest issues in implementing a guaranteed job policy may be geography, Shambaugh said.

Take Massachusetts vs. Mississippi. About 19 percent of Massachusetts workers are paid less than $15 an hour. By contrast, 40 percent in Mississippi fall below that threshold. So a guaranteed job presents a potential economic shift broader than just putting unemployed people back to work.

"What would happen if you put a $15 job guarantee there? Would 40 percent of the currently employed people decide 'Yes. I'll take the job guarantee'? What would you do with them?" Shambaugh said. Those are the "sizable shifts" that would occur, and "that, I think, is an important thing to think through."

The private sector might lose workers

Some industries, like food service and retail, could face massive changes, the report said. If the federally guaranteed jobs include child care, for instance, workers may switch to those jobs, giving private employers new competition. If a federally subsidized job raised wages, private employers like grocers and construction firms could risk losing their workforce or be forced to raised wages to match.

Top 10 industries with large numbers making less than $15 that might be hit include restaurants, grocery and department stores, travel services, home health care, gambling and recreation, nursing care and hospitals, according to the report.

A $10 guarantee, by contrast, wouldn't hit most industries as hard because fewer workers would be likely to move to the guaranteed job, the study said.

Pilot program may be good test

Targeting downtrodden areas might be one way to test the idea, to see who is affected and who is drawn to the jobs, Shambaugh said. "There's a very good argument for doing some pilots in particular in places that are quite depressed."