Ohio Amish face unfamiliar life in prison

CLEVELAND Sixteen Amish men and women who have lived rural, self-sufficient lives surrounded by extended family and with little outside contact are facing regimented routines in a federal prison system where almost half of inmates are behind bars for drug offenses and modern conveniences such as television will be a constant temptation.

Prison rules will allow the 10 men convicted in beard- and hair-cutting attacks on fellow Amish in eastern Ohio to keep their religiously important beards, but they must wear standard prison uniforms instead of the dark outfits they favor. Jumper dresses will be an option for the six Amish women, who will be barred from wearing their typical long, dark dresses and bonnets.

It's unclear where the Amish will serve their sentences, but some of the nearest options include men's prisons in Elkton, a 90-minute drive southeast of Cleveland, and in Loretto, Pa., and women's prisons in Lexington, Ky., and Alderson, W.Va. The dates they have to report could come any day.

Visits from family members might be difficult since they don't drive modern vehicles. During the trial, relatives hired van drivers to take them more than 100 miles to the trial in Cleveland, where they often filled most courtroom seats.

"Amish people grow up with very strong communal connections and large extended families and participating in community activities, so being suddenly severed from that and isolated would certainly be a major change," said Donald Kraybill, a longtime Amish researcher and professor at Elizabethtown College in the heart of Pennsylvania's Amish country.

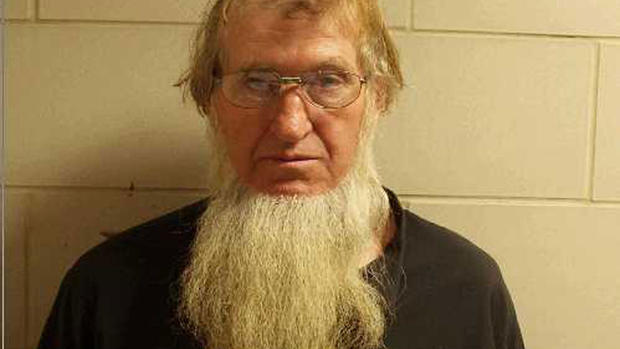

The defendants, all members of the same Amish sect, were convicted in September of hate crimes in 2011 attacks meant to shame fellow Amish they believed were straying from the strict religious interpretations espoused by the sect's leader. Fifteen of them received sentences ranging from one to seven years; the ringleader, Samuel Mullet Sr., got 15 years.

They all rejected plea deals that offered leniency, with some young mothers turning down possible chances for probation.

- Ringleader of Amish beard-cutting attacks sentenced to 15 years

- First witness details Amish beard-cutting attack

- 16 Amish in Ohio beard attack case reject plea

- FBI arrests 7 Amish on hate crimes charges

- Son attacks father in latest Amish beard-cutting

Amish communities have a highly insular, modest lifestyle, are deeply religious and believe in following the Bible, which they believe instructs women to let their hair grow long and men to grow beards and stop shaving once they marry.

Prosecutors say the 16 defendants targeted hair because it carries spiritual significance, hence the hate crime prosecution. The defendants had argued that the Amish are bound by different rules guided by their religion and that the government had no place getting involved in what amounted to a family or church dispute.

Most of the men were locked up, often in less strict local jails, after their arrests and will have some idea of what to expect in prison. The women remained free during the trial, and several have asked to stay out of prison during their appeals. The judge has rejected at least one such request, and more are pending.

The timing for moving those locked up to federal prisons and for those still at home to report to begin serving terms will be up to the prison system. When they report, they will be in the custody of the U.S. Bureau of Prisons.

The beard-cutting defendants aren't likely to see many fellow Amish in prison. In the Amish region east of Cleveland where one of the attacks took place, Trumbull County Sheriff Thomas Altiere has seen only one Amish inmate in his 20 years as sheriff, and Kraybill, the researcher, knows of just one current Amish inmate.

Attorney John Pyfer, who has represented hundreds of Amish in Pennsylvania in the past 40 years, said: "I just don't think there's a lot of Amish that go to prison, and certainly not federal prison."

The federal prisons bureau doesn't keep figures of how many Amish inmates it has held over the years.

The federal system doesn't prohibit locking up relatives in the same facility, so the defendants could wind up at some of the same locations. The defendants include Mullet Sr., four of his children, his son-in-law, three nephews and the spouses of a niece and nephews.

The response to the jailing of one beard-cutting defendant highlighted the closeness of Amish families, said Altiere, the sheriff. While two relatives visited the defendant, more than a dozen more prayed behind a glass partition.

Andy Hyde, a defense attorney for two decades in the Amish area around Holmes County south of Cleveland, has represented about 40 Amish defendants over the years and said how they handle lockup varies, much like non-Amish prisoners.

"They don't all think alike," he said. "They are as individual as we are, so it's easy to lump them all together. There are bold, there are aggressive Amish. They are quiet; they are shy."

Some low-key Amish won't stand up when threatened in prison, Hyde said, but Mullet Sr. has encouraged a tough outlook.

"Grow up," he said in a recorded phone call to a jailed son who was among the first arrested in the case. "You can take more than that. I know it's rough."

Mullet Sr. wasn't as confident about his own ability to handle prison.

"You're in there like that — I can understand that real good," he told his son. "I don't know if I could handle it."

The prison system allows an array of religion-dictated head coverings for inmates, including scarves for Jewish women and hijabs for Muslim women and, for men, turbans for Sikhs, headbands for Native Americans and yarmulkes for Jews. Baggy pants and full-length robes mandated by some faiths are prohibited.

Inmates can buy clothing items from a small selection, mostly white T-shirts and gray sweat suits, federal prison system spokesman Chris Burke said.

As for the beards, "That's not an issue, as long as it doesn't present some sort of security risk or security hazard, and I'm not aware of any case where that's happened," he said.

There's also the danger of Amish being offended, or even damaged, by access to technology, though some Amish don't eschew modern conveniences altogether, Kraybill noted. He wrote in his book "The Riddle of Amish Culture" that some Amish have selectively adopted technology, including generators to power farm equipment and refrigerated milk holding tanks.

Kraybill knows one Amish man whose prison job taught him to work with audio equipment.

In 1999, four Amish serving time in Iowa for vandalizing a neighbor's farm were released from jail early in part because officials worried they were being spoiled by television, electric lights and telephones.

Amish may have seen television at a neighbor's home or in a public area like a restaurant, Kraybill said, "but to have it available constantly would create a whole new temptation for them."