Restored and declassified videos reveal power of Cold War nuclear tests

In the thick of Cold War tensions from 1945 to 1962, the United States carried out a whopping 210 atmospheric nuclear tests, with multiple cameras filming each test from different angles. Some 10,000 of these old films were stashed away and virtually forgotten, slowly decomposing in high security vaults across the country — the images contained inside at increasing risk of being lost with every year that passed.

Now, a self-described “crack team” of film experts, archivists and software developers at the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory has brought some of these films to light for the first time in decades on the most public platform there is: YouTube. Working from a pool of 6,500 films, the laboratory team painstakingly scanned, reanalyzed, and released an initial set of 63 nuclear test films this month.

“We know that these films are on the brink of decomposing to the point where they’ll become useless,” LLNL weapon physicist Greg Spriggs, who led the team, said in a statement. “The data that we’re collecting now must be preserved in a digital form because no matter how well you treat the films, no matter how well you preserve or store them, they will decompose. They’re made out of organic material, and organic material decomposes. So this is it. We got to this project just in time to save the data.”

The films, like this one of Operation Plumbbob, are mesmerizing to watch:

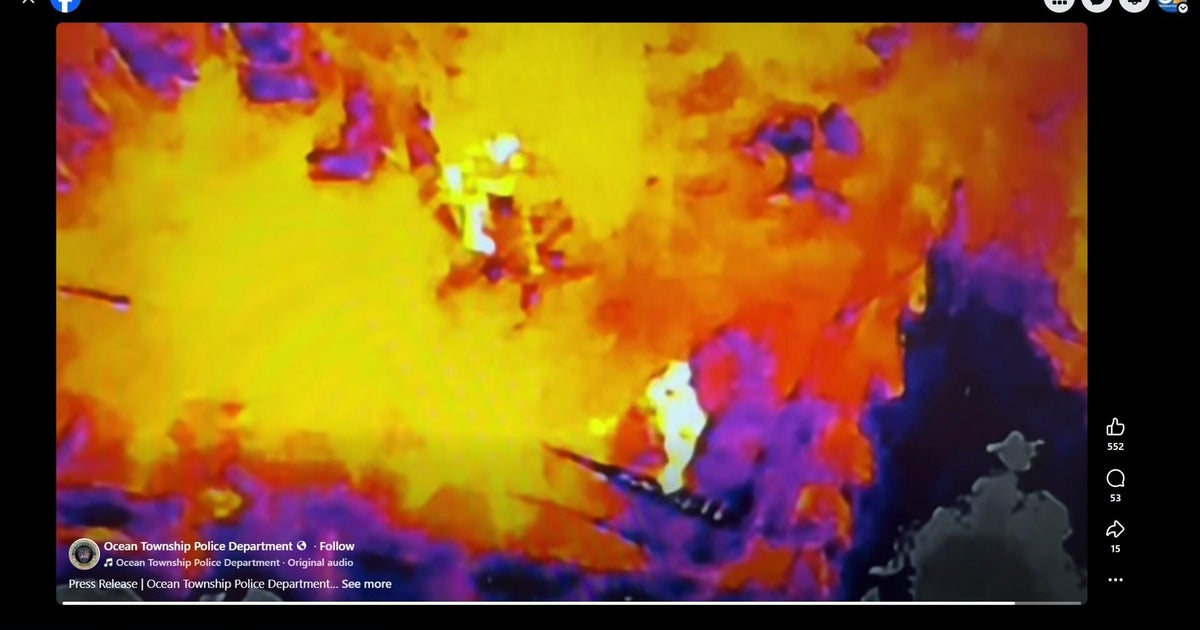

This one, showing what was called Operation Hardtack, is in vivid color:

Tracking down and reanalyzing the films has already led to new insights, thanks in part to using new, automated techniques that weren’t available to the scientists who carried out the nuclear tests last century.

“One of the payoffs of this project is that we’re now getting very consistent answers. We’ve also discovered new things about these detonations that have never been seen before. New correlations are now being used by the nuclear forensics community, for example,” Spriggs said.

The team included collaborators from Los Alamos National Laboratory and film preservation expert Jim Moye, who was also trusted by the Smithsonian to handle a rare copy of the Zapruder film showing President Kennedy’s assassination, the lab said.

In addition to strengthening benchmark data for understanding nuclear blasts, the researchers are motivated by another hope: continued nuclear deterrence.

Every president since Ronald Reagan has tried to reduce the world’s atomic stockpile. Most recently, in 2010, President Obama signed a reductions treaty with Russia.

But in December, President Trump signaled a starkly different path, at least rhetorically, when he tweeted: “The United States must greatly strengthen and expand its nuclear capability until such time as the world comes to its senses regarding nukes.” Aides at the time insisted the president’s statements did not indicate a shift in U.S. policy.

Looking at the breathtaking footage on the film clips, Spriggs said the energy released from the nuclear tests remains “unbelievable” to him.

“We hope that we would never have to use a nuclear weapon ever again,” Spriggs said. “I think that if we capture the history of this and show what the force of these weapons are and how much devastation they can wreak, then maybe people will be reluctant to use them.”