North Korea and the art of surviving sanctions

Stream the new CBSN Originals documentary, "North Korea: The Art of Surviving Sanctions," in the video player above.

There's a North Korean art scene flourishing beyond propaganda posters and far from the country's rigid borders — a scene that can be found in Florence, Italy, the cradle of the Renaissance.

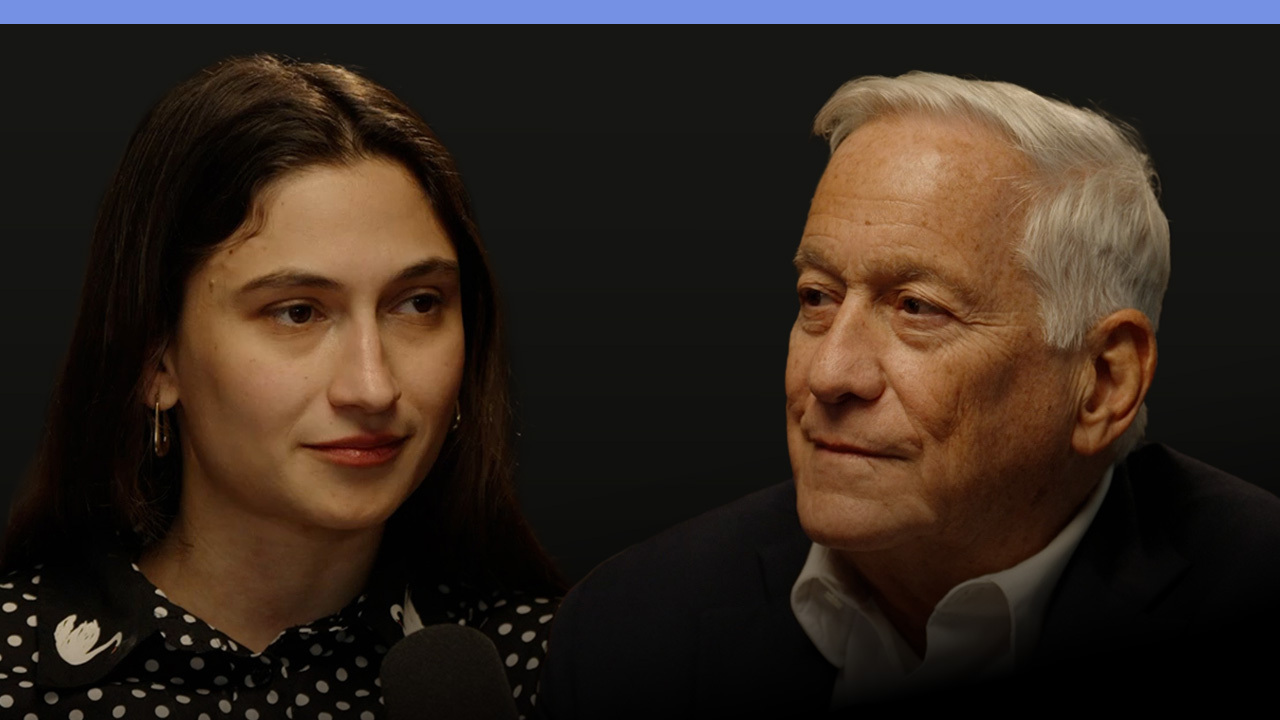

Here, in the city that nurtured Michelangelo and Leonardo da Vinci, Italian art dealer Pier Luigi Cecioni shows off the hundreds of paintings that he's imported from North Korea.

"We buy these as a company, and then we organize exhibitions and then we try to sell the works," he said. Cecioni and his brother Eugenio Cecioni have one of the biggest collections of North Korean art in Europe. They say they acquired the collection before U.N. sanctions were imposed in 2006, stalling North Korea's exports.

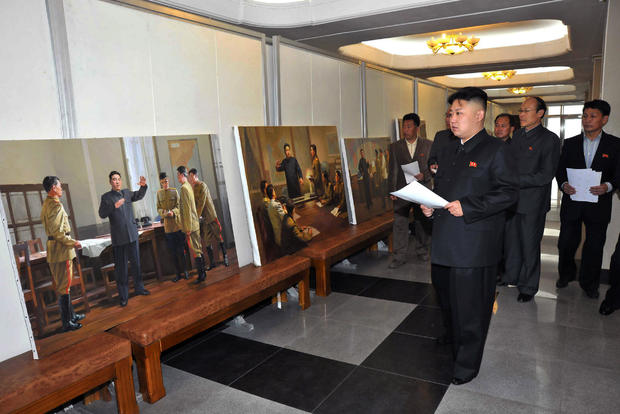

All of these works originated from Mansudae Art Studio, North Korea's massive state-run arts enterprise, based in Pyongyang. Founded in 1959, Mansudae turns out oil paintings, sculptures, portraits, embroideries and landscapes. With 4,000 employees, it is the largest art studio in North Korea, and perhaps even the largest of its kind in the world.

Mansudae ensures that North Korean culture and an idealized view of North Korean life is disseminated far and wide, and Cecioni's gallery is an example. Hanging on Cecioni's gallery walls is not just propaganda, but also lighter scenes: paintings illustrating workers with beaming smiles, and soccer players from the 1966 World Cup match where North Korea beat Italy, considered one of the greatest upsets in World Cup history. In another painting, which Cecioni refers to as a "little strange," a herd of goats surrounds a happy family.

An expert on North Korean art, Georgetown Professor B.G. Muhn, said that the socialist realism of North Korean art has a "naive, melodramatic quality. That we can't see in contemporary art."

"When you look at North Korean art, especially at first, you are struck by the difference it has with other art and the propaganda," Cecioni said. "Even though it's not all propaganda, of course. In large part it's just landscapes, portraits."

Cecioni, who said he's visited North Korea at least 10 times, began cultivating his relationship with North Korea's art studio back in 2005. The asking price for his pieces range from a couple of hundred dollars for posters to thousands for more valuable pieces, and he said the propaganda pieces are his best sellers. Pyongyang-based artists have also visited Cecioni in Italy, he said.

Cecioni said the Mansudae facility reminds him of an American campus. "There is a soccer field, there is a place for the children, but people do not live there, people go there to work," he said.

Over the years, according to Cecoini, the situation in North Korea has visibility improved, noting that now there are far more cars on the roads. He emphasizes that things don't appear to be so bad. "I do not have the feeling that the people around me are starving or that they are afraid or that they are doing things because if they don't do them they go to jail," he said, though it should be noted that the North Korean regime tightly controls what foreign visitors can do and see in the country.

In Beijing, Ji Zhengtai, a Chinese-North Korean businessman, maintains a gallery which he refers to as Mansudae's official studio abroad.

"These are art pieces; they are not military weapons," he said. Ji insists that North Korea has no control over his gallery, Mansudae Art Gallery, and that he owns more than a thousand works.

He is happy to show off the collection — like a painting of a tiger whose eyes seem to follow you across the room. But when asked about finances, and whether money is filtered back to North Korea, Ji mostly dodges the question. He also refrains from discussing artwork as a commodity. "It is vulgar to talk about it this way," he said. "When I started out I did have making money in mind. But after time, I liked the art more and more; my collection became bigger and bigger."

North Korea's repressive authoritarian regime has been under international sanctions since 2006, when it carried out its first nuclear and ballistic missile tests. A growing list of sanctions restricted trade and choked off access to foreign currency. But through the Mansudae Overseas Project, a part of Mansudae Art Studio continued to help rake in cash for the regime.

In August 2017, sanctions specifically targeted Mansudae. According to the U.N. report, Mansudae Overseas Project "engaged in, facilitated, or was responsible for the exportation of workers from the DPRK [North Korea] to other nations for construction-related activities including for statues and monuments to generate revenue for the Government of the DPRK or the Workers' Party of Korea." Due to sanctions, a travel ban was set on Mansudae, and their global assets were frozen.

But years of work by Mansudae not only succeeded in bringing many millions of dollars back to North Korea, it also helped build relationships with other countries around the world.

Mansudae has projects in at least 15 countries, but its most lucrative relationship has been with Africa. Enormous bronze monuments throughout the continent brought in an estimated $260 million as of 2016. A North Korean construction firm built the African Renaissance Monument in Dakar, Senegal, which cost Senegal $27 million — a huge sum for the impoverished nation. At a 160 feet tall, it is the largest monument in Africa.

The project seems to have brought North Korea more than just much-needed currency. As the monument's director, Georges Diatta, told us, it also brought goodwill.

"If the Senegalese government accept North Korean society to build this monument, it was because they have got a good relationship," Diatta said.