North Korea: Stories of escape

SEOUL South Korea is home to an estimated 25,000 North Koreans. They are the primary source of our knowledge about life under what the United Nations calls the worst human rights conditions on earth. We spoke with three defectors who defied the odds:

- S. Korea to pull all workers from Kaesong complex

- Translating N. Korea's rhetorical rage

- Complete coverage: North Korea Tensions

The rude awakening:

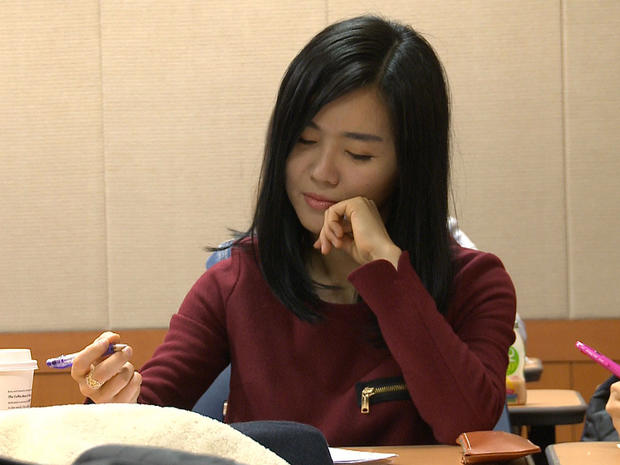

Perfectly coiffed in her chic dress and heels, Hyeonseo Lee, 33, is indistinguishable from the crowd at Seoul's Hankuk University of Foreign Studies -- a prestigious institution where President Obama delivered an address during a 2012 visit.

But Hyeonseo's outgoing demeanor belies her terrifying journey from North Korea.

Born in the border province of Hyesan, Hyeonseo was the daughter of an air force officer and a company executive. Her childhood was happy, steeped in an abiding hatred for Americans who were blamed for everything from the divided peninsula to a house fire down the street.

Juxtaposed against this arch-enemy was the saintly Kim dynasty. "When I was young, I thought Kim il-Sung or Kim Jong-il is hero," she said, referring to the first two dictators of North Korea.

Hyeonseo's illusions were shattered, however, when she was just 15 years old.

Her mother came home with a letter her co-worker had received from her (the co-worker's) sister. The sister and all her family members were starving to death during the famine of the late 1990s.

"When you read this, all five family members will not exist in this world, because we haven't eaten for the past week. We have no energy. Our bodies are so weak. We are lying on the floor together and we're waiting to die," read the letter.

The family did die from hunger.

When Hyeonseo heard her mother read the letter, it was a "huge shock" -- the first time she realized she wasn't actually living in paradise (although she had seen her first public execution at age seven), and it would eventually set her on a course for defection.

Meanwhile, the bright lights of China across the border beckoned.

"I thought, my country is better than China. In the world, my country is the best. Why they have lights? Why we don't have?"

Hyeonseo finally crossed the border, became fluent in Chinese, and made her way to South Korea, but knew that her escape would mean retaliation against her family. She returned to the border, to guide them to safety.

The fugitives transferred from bus to bus, slowly making their way southwest across China towards the Laotian border on fake Chinese IDs, when a suspicious Chinese policeman nearly blew their cover.

"They started asking questions. 'Where's your hometown? Where are you going?' They were looking for North Korean refugees."

Discovery of their real identities would have meant forcible repatriation, prison camp, and almost certain execution for Hyeonseo, who carried a South Korean passport. She had to think fast.

"The policeman kept calling my mom's name. I just had thousands of thoughts through my head." In fluent Chinese, she said, "'these are deaf and dumb people. They can't understand, they can't speak, and I'm just leading them.'"

Miraculously, the family was allowed to continue on, only to be arrested in Laos. Only the chance intervention of a Good Samaritan tourist, who paid their fines and helped them travel to South Korea, saved their lives.

When her mother finally laid eyes on Seoul, her first words were "wow, it's true. There are a lot of cars on the street." The traffic jams she had seen in illicitly distributed South Korean movies, she had assumed, were fake -- all the cars in the country collected for visual effect.

Now an iconic face of North Koreans in exile, Hyeonseo says one of the best ways to help North Koreans is by providing aid and opportunities to refugees, who have developed their own secret networks and conduits for sending information and assistance back home.

Many defectors struggle to shed the intense indoctrination of the North Korean regime, but Hyeonseo seems to have weathered the transition with ease. The child who was taught to hate the U.S. is now engaged to a classmate from Wisconsin.

You can't live by the rules

By his own admission, Oh Song Il was an accomplished con-artist -- and proud of it.

"In the North, people say, 'oh, he's a smart guy. He doesn't get caught, and does well.'"

Oh now works at a radio station in Seoul, beaming news into North Korea. Survival, he said, depends on total mastery of the rules -- and then figuring out how to beat the system.

For the crime of viewing, making and selling illicit movies, he and his entire family were expelled from Pyongyang and sent to Hamgyong Province, on the Chinese border.

It was not just backward, but "a century" behind the showcase capital of Pyongyang, the only part of North Korea foreigners are ever allowed to see.

Famine was a constant.

"People constantly dream of being fed well, just once in their lives. This dominates everyday life."

After decades of harsh repression, North Koreans have evolved into the ultimate survivors, Oh said, describing how, in the absence of state rations, resourceful citizens created black markets to import food from China and distribute it on their own.

Oh's street smarts were put to the test as he helped his family escape. The trick, he said, was to erase any paper trail. "It means leaving no border-crossing records. Erasing criminal records for escape attempts."

When police arrived to check his family's whereabouts, he feigned ignorance. "I tell them, it was their fault for losing my family, and they should go look for them and bring them back to me."

In 2011, he was finally able flee the North and join them.

North Koreans are "tired":

Seo Jae-Pyoung, who defected in 2001 after he was caught listening to South Korean radio, works as a political activist in Seoul.

"North Korean civilians and soldiers are tired" of the near-constant preparations for war, Seo says. The regime's warnings of an imminent threat fall on deaf ears, he argues.

Combat readiness, he said, means North Korean soldiers must sleep with their boots on and do more watch duty shifts. Hospital patients are moved to underground tunnels.

An estimated 10,000 Chinese cell phones are in circulation in North Korea, he said. Many are used for cross-border trade, but some are distributed by pro-democracy activists. Either way, cell phones have become vital for citizens behind North Korea's Iron Curtain.

Seo dismisses the threats emanating from Pyongyang, recalling a North Korean proverb: "A barking dog doesn't bite."

He adds, however, that "once the sword is drawn, it's awkward to put it away without doing anything."

He still expects some kind of small-scale military action, or perhaps a cyber-attack.

"They must follow their talk with action."