North Carolina court upholds GOP-drawn maps

In a unanimous decision, North Carolina judges upheld maps drawn by Republican legislators and rejected claims of "extreme partisan gerrymandering" made by Democratic-leaning voting rights groups.

While challengers to the maps plan to appeal the decision to the state supreme court, where Democrats hold four out of the seven seats, the ruling by the lower court is a win for Republicans in one the first major legal decisions on redistricting before the midterm elections this year.

The initial congressional map passed by North Carolina Republicans is likely to add two more Republican-leaning seats, raising the number from eight to 10, at the expense of multiple Democratic incumbents.

Democrat G.K. Butterfield's 2nd District went from a seat President Biden won by 54%, to the only pure "toss-up" seat. Butterfield, as well as Democrat David Price, have announced they will not run in 2022.

Although Democrats won approximately 50% of the votes in U.S. House races in 2020, they currently hold five Congressional seats compared to eight for Republicans. North Carolina's population growth this past decade, due largely to minorities in a mix of Democratic and Republican counties, earned the state a new 14th Congressional District.

In the ruling, the panel of three superior court judges say redistricting "is an inherently political process," and that challengers did not present enough about the maps to show "extreme partisan gerrymandering."

"This Court neither condones the enacted maps nor their anticipated potential results. Despite our disdain for having to deal with issues that potentially lead to results incompatible with democratic principles and subject our State to ridicule, this Court must remind itself that these maps are the result of a democratic process," they write in their ruling.

"There is no requirement that each party must be influential in proportion to its number of supporters," they add.

The judges suggested that a claim of racial gerrymandering might have held more sway with the court, noting that challengers could have made a claim that the partisan gerrymandering diluted the minority vote under the Voting Rights Act, but "either for strategic reasons or a lack of evidence," plaintiffs chose not to.

"It potentially would be easier to prove a violation of the Voting Rights Act, as one only need prove effect and need not prove intent," the judges wrote.

The state's League of Conservation Voters and other challengers called the decision "disappointing" and are now turning to the state supreme court. A U.S. Supreme Court decision in 2019 established federal courts do not handle partisan gerrymandering cases.

"We remain confident that our conclusive evidence of partisan bias, obfuscation, and attacks on Black representation, from expert testimony to the mapmakers' own admissions, will convince the state's highest court to protect voters from nefarious efforts to entrench partisan power at the expense of free elections and fair representation," said Hilary Harris Klein, a senior counsel for voting rights at the Southern Coalition for Social Justice.

During a trial earlier this month, Jowei Chen, a University of Michigan political scientist professor brought in to testify by the case's plaintiffs, compared the map to other computer simulated maps he generated. He said that 97% of the thousand maps were less biased for Republicans.

"It's a statistical outlier," Chen said. "It creates a level of Republican bias that cannot be explained by North Carolina's political geography or by the General Assembly's August adopted criteria."

Defendants of the map questioned the credibility of the algorithms, and said it doesn't reveal an obvious partisan gerrymander.

Republicans argued their process of redistricting has been the most transparent, though at one point "concept maps" were shown to Republican legislators during the redrawing period. They also argued that while racial gerrymandering violates the state's constitution, partisan gerrymandering does not.

"What is the line between permissible and impermissible partisan considerations when drawing a map? The fact is that is an unanswerable question, unless the courts try to answer it with brute force alone," Phil Strach, an attorney for the Republican lawmakers, said in his closing argument.

Republican lawmakers made a similar argument when their maps were challenged in 2019. A panel of judges ruled a redraw, the second time their Congressional lines changed last decade, due to "extreme partisan gerrymanders."

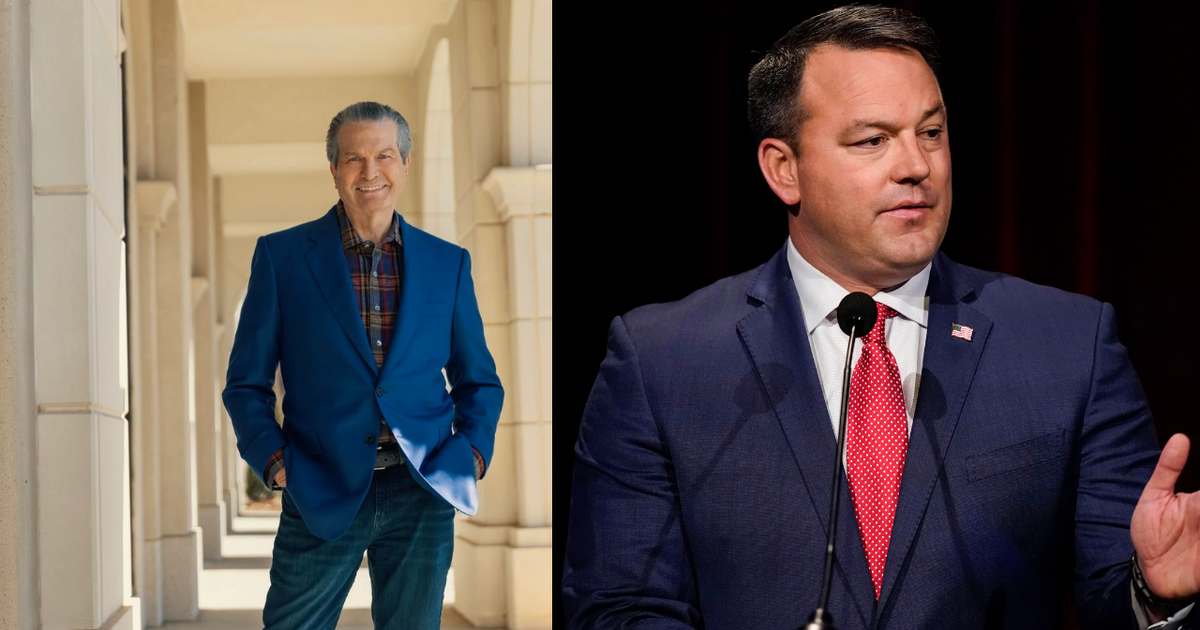

The North Carolina judges also issued a halt in candidate challenges, in response to an attempt to disqualify Republican Madison Cawthorn from the ballot, until a final court decision on congressional lines is reached.

There are partisan gerrymandering cases in Alaska, Nevada, Maryland and New Jersey, and racial gerrymandering cases in Texas, Arkansas, Alabama, Georgia, Illinois and South Carolina, according to the Brennan Center. There's also a slate of redistricting cases in front of Ohio's Supreme Court, which heard oral arguments in December 2020.

Thirty-three states have completed congressional redistricting, including the six states that have just one representative in the House. Some of the notable states left are Louisiana, Tennessee, Florida and New York, where a redistricting commission was sent back to the drawing board after legislators rejected their first set of proposals.