He has four murder convictions. His victims' families don't want him to die on death row.

Tony Eden says he narrowly escaped being taken hostage during the 1985 riots at the Tennessee State Prison in Nashville. The former corrections officer, now 61, was cornered by inmates as buildings were set ablaze and burned.

Eden credits an inmate, named Nicholas Todd Sutton, with saving his life that day. Thirty-five years later, Eden found himself advocating for Sutton to be spared from a similar fate.

Seven former and current officials, including Eden, requested Lee to commute Sutton's death sentence. The petition cited three separate occasions where Sutton stepped in to protect corrections staff from violence.

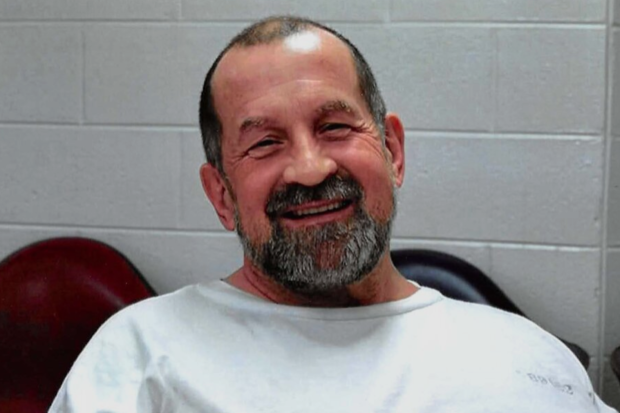

Tennessee Governor Bill Lee denied Sutton's clemency petition on Wednesday, saying after "careful" consideration of the request, he would not be intervening. Sutton, 58, is scheduled to be executed by the electric chair Thursday.

"I have four boys and a girl now who probably wouldn't be here if that day turned out differently," Eden told CBS News. "I wouldn't have the life I have today if it weren't for Nick."

Kevin Sharp, one of Sutton's attorneys, told CBS News this type of support is "unusual."

"You need people like Nick who make the place safer," Sharp added. "He's not getting out, all we're asking for is the governor commute his execution. He would still die in prison, just not by the electric chair."

Sutton has four murder convictions. The first three were committed in 1979 when he was 18 years old. He was handed down three life sentences, including one for killing his own grandmother.

Six years later, Sutton was sentenced to death for fatally stabbing a fellow inmate. His lawyers claim it was a "kill or be killed situation" after another inmate allegedly attacked him.

A neuropsychologist evaluation found trauma from childhood abuse caused severe developmental impairments for Sutton, something his lawyers say was never considered during his capital case.

Advocates now argue that Sutton has undergone a "profound transformation" during his 34 years on death row. Prison records show no serious disciplinary actions since 1990 and lawyers claim he makes the prison safer through counseling and caring for other inmates.

"The death penalty takes so long to administer, you're commonly executing people who are very different than the youthful offender who committed the crime," Evan Mandery, a professor at the John Jay College of Criminal Justice, told CBS News. "Mr. Sutton's case seems like a very extreme example of this."

Sutton was moved to the Riverbend Maximum Security Institution shortly after his capital trial in 1985. When the Tennessee State Prison closed a few years later, Eden was moved there, too.

Eden said despite the fact that Sutton saved his life, he never asked for a favor in return.

Although, there was one thing.

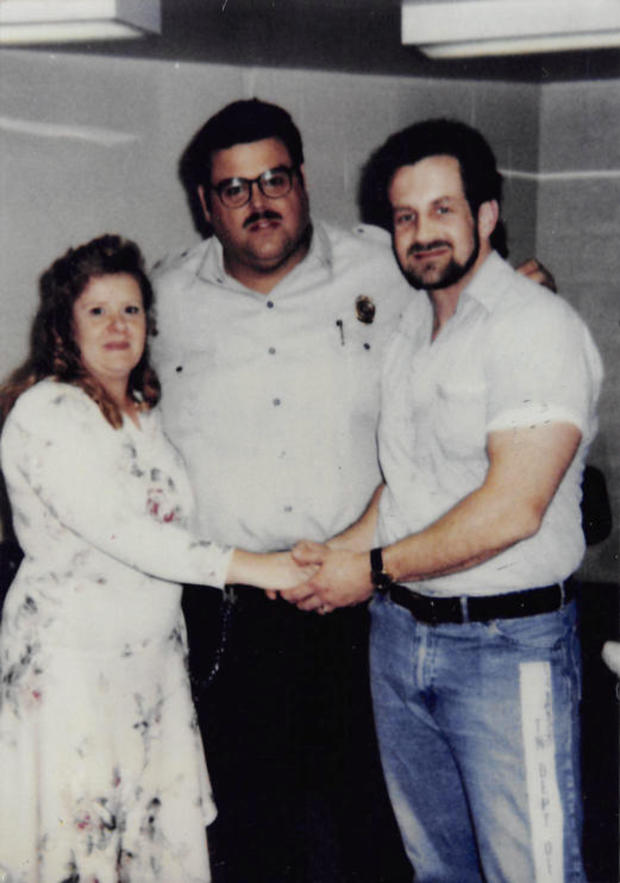

"He asked me to be the best man in his wedding," Eden recalled. "That's the only thing he ever asked for that I know of. And all he wanted was just for me to stand there."

Sutton is about to celebrate his 26th wedding anniversary to his wife, Reba, a woman he fell in love with through a pen-pal program. Eden said the ceremony happened inside the visitation gallery in the back of the death row unit, where Sutton has fielded visitors for decades.

The eldest daughter of the inmate Sutton killed has joined the effort to spare his life. In a clemency petition filed on January 14, she advocates against the execution, saying "the pain and suffering her family has endured would only be made worse" if Sutton was killed.

"You don't even have surviving victims who are clamoring for revenge," Mandery, an expert on the death penalty, added. "On the pro and con leger, I can't come up with anything on the pro side for why execution would be important to do."

This week, Sutton was moved to separate housing for what's known as death watch. He handed in his white death row uniform for what Sharp described as yellow operating room scrubs. Security has been tightened, and he's only allowed to speak to visitors through a glass pane.

Data shows capital punishment in the U.S. is steadily declining. There were 825 fewer death sentences between 2010 and 2019 compared to the 10 years prior. Last decade's death sentencing rate was 89 percent lower than a peak in the mid-1990s.

If he's not granted clemency, Sutton will become the 1,156th person to be executed in the United States since 1976. He will be the 13th from the state of Tennessee.

"He's hopeful but understands there's decisions that need to be made," Sharp said after a recent visit. "He feels badly for his family, he knows how painful this is going to be for them."