How IEDs may be physically causing PTSD

Editor's Note: Since this story aired, we have received many inquiries about how to contact Dr. Daniel Perl and The Center for Neuroscience and Regenerative Medicine. Here is that information: http://www.researchbraininjury.org or 1-855-366-8824.

A new medical discovery has profound implications for wounded warriors. It's a previously unknown type of brain injury uncovered in veterans who are exposed to the invisible wave of energy that erupts from high explosives. The evidence was found in the brains of veterans who died. And tonight, we have a rare opportunity to introduce you to one of the vets who made the discovery possible. Retired Army Sergeant First Class Brian Mancini killed himself in 2017 after descending into psychosis. But we met Mancini years before, in 2011, after he made a nearly miraculous recovery from the impact of a roadside bomb in Iraq. There's no one better to begin this story, than the late Brian Mancini himself.

Brian Mancini: I got hit in the face. I knew pretty early that I had lost my eye. I didn't know how severe my injuries were, but I knew I was hurt very bad.

We met Brian Mancini six years before his suicide. We had followed a group of wounded vets back to Iraq on a therapy program, endorsed by the Pentagon, designed to help them come to terms with the day they were wounded and leave that day behind.

Brian Mancini: You know, we often hear about guys that carry these heartaches their whole lives. And it slowly erodes them. I don't want to be that guy, you know? I want to be able to have a successful life and not burdened with the demons that I see here.

Brian Mancini: I'm glad I'm alive.

On that return trip to Iraq, Mancini visited the field hospital that saved him.

Brian Mancini: My whole face has been rebuilt. I used to look like Brad Pitt but this is what I got stuck with.

Brian Mancini: I have a titanium mesh plate in my forehead. They rebuilt my whole orbital socket. My sinuses were replaced or rebuilt.

Scott Pelley: How many surgeries did that come to?

Brian Mancini: I have no idea. I have no idea.

"Brian would often say, 'I don't know if this is real... or if I dreamt it.'"

Years of surgeries, pain and struggle were witnessed by Brian Mancini's brother and sister, Michael and Nichole.

Michael Mancini: Oh, he was a patriot. He loved this country. He loved this country.

Nichole Mancini: He was a natural leader, and I think that the military was a natural fit for him. And he was good at his job, and he loved it.

After his recovery, he created a new job for himself. At home in Phoenix, he founded "Honor House" to provide wounded vets with therapies that helped him—including yoga, acupuncture, and especially fly-fishing.

Brian Mancini: He came leaps and bounds. And Brian two years ago was the best Brian I've ever known in my life.

But as he reached his peak in 2015, Mancini suddenly began to suffer delusions. He imagined the government was spying on him, that members of the Honor House board were with the CIA. And he thought he was being tracked with cell phones.

Michael Mancini: It was delusional, it was irrational, it was like, a progression.

Nichole Mancini: He wouldn't let us have our cell phones around him.

Michael Mancini: Very paranoid.

Nichole Mancini: His mind had started to almost turn against him. And people that—

Scott Pelley: His mind had turned against him?

Nichole Mancini: Yeah. Brian would often say, "I don't know if this is real or if I had if I dreamt it."

The Honor House board took control of the charity from Mancini. He had been depressed before, but not insane. Last year, Mancini donated his life savings to his church, drove to this remote canal, and shot himself in the head. The betrayal of his mind had been so sudden, so shocking, that his family was certain there must be a cause that no one understood.

Michael Mancini: And the first initial thought to me was, "I need to find someone who would take my brother's brain tissue for further study and further research."

The Mancini's found neuropathologist Dr. Daniel Perl.

Perl oversees the brain tissue repository at the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, the military medical school in Bethesda, Maryland. Perl also wondered whether some torments of war might be rooted in an undiscovered kind of brain injury caused by the supersonic pressure wave of high explosives.

Dr. Daniel Perl: That started in World War I and we had the whole issue of shell shock. And then in World War II, we had battle fatigue. Then in Korea, we had PTSD. I mean, these were all expressions of responses to being in warfare, much of it being exposed to blast. And we knew nothing about what was going on in the brain.

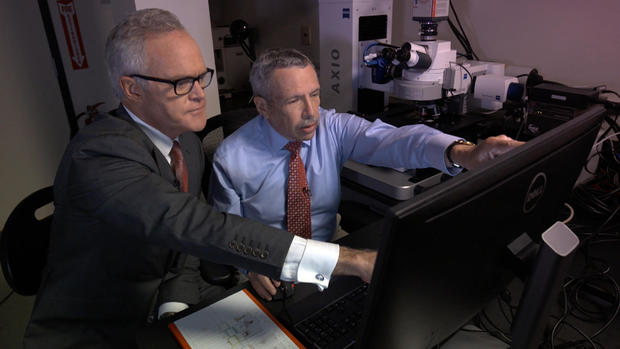

Perl's team sliced brain tissue from eight veterans and examined the tissue under a microscope. Rare for its power.

Scott Pelley: That doesn't look like the one I had in high school.

Dr. Daniel Perl: No, it's not.

Perl says his microscope is thousands of times more powerful than the best MRI. And it helped them discover this previously unknown form of brain injury when Perl compared the brains of the vets to civilians who had injured their brains in car wrecks.

Dr. Daniel Perl: The difference is just so dramatic.

Scott Pelley: These on the left are people who suffered--

Dr. Daniel Perl: A single individual's brain who suffered an automobile accident. A single individual who was exposed to blast. Stained identically for scarring.

Scott Pelley: The brown--area is the stain that reveals the scarring and you don't see it in the person who hit their head in the automobile accident.

Dr. Daniel Perl: That's right.

Dr. Daniel Perl: When an IED goes off there's a tremendous explosion. And with the explosion comes the formation of something called the blast wave. And it is sufficiently powerful to pass through the skull and through the brain. And when it does that-- it does damage the brain tissue.

Scott Pelley: Do you have a slide of Brian Mancini's brain?

Dr. Daniel Perl: Yes, we do.

The dark brown is scarring, running along lines where two types of brain tissue meet, the so-called gray matter and white matter.

Dr. Daniel Perl: The locations were areas of the brain that had differing densities. This was the interface between gray matter and white matter, between brain and fluid, such as spinal fluid, or brain and blood.

Scott Pelley: Why do you see the scarring where the white matter and the gray matter come together?

Dr. Daniel Perl: The white matter have a somewhat higher density than the gray matter. And that's where the energy of the blast wave is released.

Scott Pelley: They bang together.

Dr. Daniel Perl: In a sense, yeah.

Scott Pelley: Do you see the scarring at these interfaces throughout the entire brain?

Dr. Daniel Perl: We're looking at that now, okay? By and large, yes.

Evidence of this scarring was found in all of the veterans - none of the civilians.

Scott Pelley: Do you believe that you're going to find a connection between this and post-traumatic stress disorder?

Dr. Daniel Perl: In a sense, we already have. Every case that we've looked at has been diagnosed with PTSD And what that connection is, the nature of that connection, whether the scarring in the brain leads one to be more apt to develop PTSD, or whether there's so much overlap between the symptoms that one gets with the damage in the brain that it looks like PTSD, we don't know yet.

Earlier this season we reported on research by another laboratory into vets who showed evidence of "CTE" the kind of brain injury found in football players. Dr. Perl says his team has discovered something distinct from CTE.

Dr. Daniel Perl: Very different, okay? One is a huge blast wave that almost destroys his face, passes through his brain. It's a one-time thing. OK? It's not the sorta daily and weekly impact injury that an NFL player has. The other thing is that our service members are coming home from deployment symptomatic. By and large, CTE in the football player, for instance, occurs in their retirement, after they've played.

Scott Pelley: Years later?

Dr. Daniel Perl: Years later, right. They become symptomatic. So the timing of it seemed to be a very different proposition.

Scott Pelley: But it's absolutely clear to you that Brian Mancini did not have CTE?

Dr. Daniel Perl: That's right. We looked very carefully for CTE in Brian's brain. And he just did not have it.

Scott Pelley: So what you and your colleagues have discovered is something new?

Dr. Daniel Perl: Yes. Yes. This is new. This, this has changed thinking about blast exposure and its consequences.

We were able to add something to Dr. Perl's research that he rarely sees, a description of the blast that wounded one of his deceased subjects.

Brian Mancini: Most of my forehead was blasted out, I had a basal skull fracture along with some fractured vertebrae in my back and some burns and shrapnel. When I was doing the assessment of my injuries, I remember laying down and opening my mouth as wide as possible and reaching in and scraping the debris that had been knocked loose, and the blood, from my airway so I could breathe. And shortly after that, I lost consciousness.

Dr. Daniel Perl: It's just stunning to see this it's not something I normally get to experience. I mean that he survived this injury is just remarkable, much less what happened afterwards.

Now that the discovery is known, Perl hopes research can begin into improving the lives of those who suffer with this hidden wound of war.

Scott Pelley: What's your theory today on how this damage manifests itself in a living human being?

Dr. Daniel Perl: Well, obviously wherever there is damage, there must be some loss of function. Persistent headaches. They have problems with sleep. They have problems concentrating, memory problems swings of mood, anger management problems.

The discovery is a lone fact that raises many questions; can the scarring ever be seen in a living patient? How do the scars affect the mind? And what can be done?

Scott Pelley: If Brian Mancini had come to you in the last year of his life, would you have been able to do anything for him?

Dr. Daniel Perl: No, I don't think so. I don't think so. We're not there yet. We have a lotta people now beginning to take it seriously and begin work on it. It's not just us in our lab. It's really been a game changer in terms of our approach to this problem.

Dr. Perl is now searching for preserved brains of World War I veterans to see if the scarring dates to the beginning of widespread use of high explosives in war. Brian Mancini's life was devoted to wounded warriors—first as an Army medic, then in rehabilitation. And now, even in death, his work to heal continues.

Scott Pelley: And this is what Brian would've wanted?

Michael Mancini: Oh, absolutely.

Nichole Mancini: Without a doubt.

Scott Pelley: Brian is still serving his country.

Michael Mancini: Amen.

Brian Mancini: I wouldn't trade any of these horrendous and horrific experiences for anything there's a lesson in everything that we endure in life, And if we can clear all the chaos away and all the heartache away, we can receive that lesson "Why was I here? What was this for? Why did this happen?" And kind of get some of those answers. And I think that helps in healing long-term.

Produced by Henry Schuster. Associate Producer, Rachael Morehouse.