New Orleans mayor Mitch Landrieu looks back on his eight years in office

In the last year Mitch Landrieu has built a national profile that many political observers think could lead to a presidential run. But as the New Orleans mayor approaches the end of his eight-year tenure in office, he told CBS News contributor Jamie Wax that he hopes to stay out of politics.

"People say, well, you know, you're a rising star. I said, yeah, it took me 30 years to become an overnight sensation," Landrieu told Wax.

It may have taken Landrieu 30 years to build a name for himself across the country, but he's always been a household name in New Orleans. His father, Moon Landrieu, led the city for eight years in the 1970s.

Politics, however, wasn't his first love – it was acting.

"I wanted to be a professional actor. That was my first dream," Landrieu said.

Luckily, he hedged his bets in college and double majored in theater and political science at Catholic University.

"People misunderstand what theater school is really about. It's not about adding on and adding characters. It's about stripping down so that you can be authentic," he said. "You go look at Shakespeare, Rogers and Hammerstein, or Stephen Sondheim, you go back and look at the script that was written for 'Hamilton' and there are essential truths and there's history. ... All of those skills wound up helping me when I eventually, after law school, decided to go into politics."

In between unsuccessful runs for mayor, Landrieu would serve as Louisiana's lieutenant governor. He was elected the city's mayor in 2010. Seven years later, Landrieu's speech on the removal of the four Confederate monuments caught the country -- and even him -- by surprise.

"It was the truth as I saw it," he said of the speech. "It was not meant to be a speech to a national audience, but it evidently spoke to something that touched people across the country."

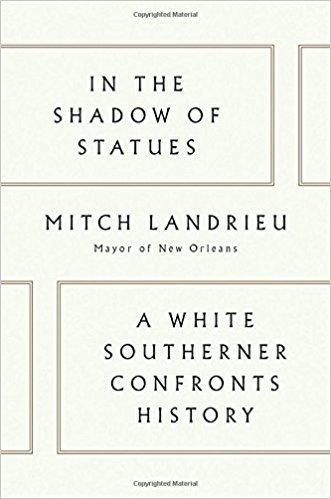

The speech became the impetus for his book, "In the Shadow of Statues: A White Southerner Confronts History," which was released in March. Landrieu writes about his inability to get contractors or equipment from in-state even after approval from the legislative, judicial, and executives branches of government.

"Even after that, these individuals engaged in what I would call domestic terrorism. By threatening the lives of people that worked for the government, are contracted with the government, and said that if you take that down, we will ruin your life or we will hurt you," Landrieu said.

Landrieu's father warned him about the risks of removing the monuments, even though it was a road Moon Landrieu, a pioneering civil rights advocate in the city, helped pave.

In the book, Landrieu recalls a moment when his father told him to go into every corner bar.

"Because 30 years earlier, he had gone to the corner bars. Well, of course, many of these at that time were white bars. ... My father was credited with work with the African-American community, and the white community really never forgave him for that. But he was remembering what they were back then. So he bothered me about it so much. He really aggravated me. I finally went into one of the bars. And I saddled up to a guy and said, 'Hey, you know, I'm Mitch Landrieu.' He looked at me, he goes, 'I know who you are. I hate your father and I'd never vote for you.'"

All the family's political experience hasn't shielded Landrieu from some issues that have traditionally plagued New Orleans. The murder and incarceration rates for young African-American men remain among the highest in the country under his tenure.

"The message that the statues is sending is a message that's been sent since slavery has been here," he said. "These monuments in a real way are death. ... They're not things that are enabling people to do better. They're actually destroying people's souls."

And just last year he seemed caught off guard when a number of the city's emergency drainage pumps stopped working after a storm, causing massive flooding and forcing the resignation of top city officials.

"When I took this city over, this city was completely broken. ... The infrastructure relating to pumping in this city is older than Calvin Coolidge," he said.

"Now, we've spent almost every waking moment in the eight years trying to fix the system," he said. "But you can't fix it overnight. The city's been wet more times than you can count. And it's going to get wet again. You can't fix what you don't have the money for and why a lot of mayors are really frustrated that infrastructure bill is stuck in Congress," he said. "It takes billions and billions and billions of dollars to do this. ... You see it in Flint, Michigan. You actually see it all over the place. You see it in New York right now with the subway. And so mayors have been really raising their voices."

Landrieu boasts about new business investment in New Orleans, including construction of a new $1 billion airline terminal, along with a record 11 million visitors last year and more than 50,000 new residents.

"We've created 20,000 jobs. We're actually helping built the rocket that's gonna go to Mars," he said. "And so the city of New Orleans, although people think about it Mardi Gras and fun this is – we have a knowledge-based economy now. ... As Washington continues to get stuck, cities are getting a lot smarter, a lot faster, a lot more entrepreneurial."

Last month, Landrieu helped celebrate the city's 300th anniversary. And the mayor says he's proud of the last eight years leading the city he loves.

"You know, there's an adage that you have to walk by faith, not by sight. That doesn't mean by ignorance but you get an intuition over time about what the right pathway is," he said. "Like everybody, we make lots of mistakes. If you're not making mistakes, you're not trying. ... I think we got it pretty right most of the time."

When Landrieu leaves office on Monday, history will again be made with the swearing in of his successor LaToya Cantrell, the first woman and first African-American woman ever to be elected mayor of New Orleans.