New cooperation with Russia in anti-ISIS fight looks unlikely

President Donald Trump has often talked about working closer with Russia in the fight against ISIS. But with his administration increasingly embroiled in questions about his advisors’ closeness with Moscow, an anti-ISIS alliance looks increasingly unlikely.

“I say it’s better to get along with Russia then not. And if Russia helps us in the fight against ISIS, which is a major fight, and Islamic terrorism all over the world, major fight, that’s a good thing,” Mr. Trump said in an interview with Fox News in early February.

He also hinted at common cause with Russia in his inaugural address, saying that the U.S. should “reinforce old alliances and form new ones” in the same line that he called for uniting the world against radical Islamic terrorism.

Secretary of State Rex Tillerson struck a similar chord after he met with Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov in Germany during the G-20 meetings last month.

“As I made clear in my Senate confirmation hearing, the United States will consider working with Russia where we can find areas of practical cooperation that will benefit the American people,” Tillerson said at the time.

Yet these comments have not yet morphed into a plan that would merge the former Cold War enemies in any kind of joint anti-terror policy -- and insiders say that a closer relationship is not the direction that policy is moving. In fact, the possibility of a U.S.-Russian alliance in Syria is drifting further and further away.

The preliminary plan for combating ISIS, which White House officials reviewed last week, did not include a directive to collaborate with Russia. Rather, it laid out a plan to provide more for the U.S.’s unilateral engagement in Iraq and Syria. The general idea is to speed up the fight and to prevent future terror groups from strengthening.

Attorney General Jeff Sessions’ recusal from the Russian investigations, due to a meeting with the Russian Ambassador to the U.S. that he did not disclose in his confirmation hearings, means that Moscow’s efforts to influence the election are back in the spotlight. Though Mr. Trump says the issue is little more than “saving face for Democrats losing an election that everyone thought they were supposed to win,” it would be extremely difficult politically for the White House to push for closer cooperation with Russia right now.

Beyond political concerns, some experts say increased cooperation with Russia in Syria would backfire. Christine Wormuth, a former under secretary of defense for policy at the Department of Defense, sees no advantages to a joint U.S.-Russian mission in Syria. She and other military experts say there is no benefit militarily to working with the Russians in Syria, as U.S, intelligence and military capabilities are far superior to that of the Russians’.

But Wermouth also points to a lack of shared objectives in Syria. Russia is there prop up its ally, Syrian strongman Bashar al-Assad; the U.S., meanwhile, supports forces that fight both Assad’s army and ISIS.

“Russia’s activities in Syria are fundamentally in conflict with ours,” Wormuth says. “They have been bombing the opposition forces, which we have been supporting.”

During the Obama administration, Department of Defense officials repeatedly met with Russians about joint efforts in Syria, but Moscow refused to meet U.S. conditions. These fruitless meetings are the reason that many Obama-era officials at the Department of Defense and the State Department believe that all options to fuse U.S. anti-ISIS efforts Russia have been exhausted.

Others believe in the necessity of a new U.S. approach in Syria and disagree with keeping Russia at a distance. Michael O’Hanlon, a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution, favors considering U.S.-Russia collaboration on he ground in Syria.

O’Hanlon believes that rethinking the US intervention in Syria is needed on the political side, not just on the military side. This means admitting that Assad has won the war and working with Russia to take on ISIS.

“Working with the Russians is a means to an end. It is not a strategy. And I am glad that Trump is willing to do it. On this one I just hope he is not naive,” explained O’Hanlon. “But I do think that the core Russian and American interest in Syria are potentially compatible. Therefore, we should attempt to work with Russia and if we don’t we are guaranteed to fail.”

Still, U.S.-Russian cooperation in Syria, even at a limited level, remains rather dysfunctional, which is damaging to U.S. ambitions on the ground. Last week a Russian aircraft bombed a Syrian village held by US-backed forces because, it appears, they thought it was ISIS-held territory.

“It became apparent that these strikes were falling on some of the Syrian Arab Coalition positions and some quick calls were made through our de-confliction channels and the Russian acknowledged and stopped bombing there,” said Lt. Gen. Stephen Townsend, the Commander of US Forces in Iraq and Syria.

The United Nations has accused the Assad regime of war crimes, and outside groups say Russia has abetted or contributed to them. Earlier this month, the Atlantic Council’s report “Breaking Aleppo” used building security footage and satellite images to show the destruction of hospitals in the city by Russian bombs. And just last week, Russia and China vetoed a UN resolution that would impose sanctions on Damascus for its use of chemical weapons.

The U.S. was sharp in its condemnation. “Russia and China made an outrageous and indefensible choice today,” said UN Secretary Nikki Haley, speaking in the Security Council chamber after the vote. “It is a sad day on the Security Council when members start making excuses for other member states killing their own people.”

According to Wormuth, Russia’s willingness to kill civilians on behalf on the Assad regime poses ethical concerns to a closer partnership. “[The Russians] are not concerned with civilian casualties, which we view as something fundamentally important. They do not operate and conduct themselves in line with international law and military codes of conduct. To partner with them would sully the hands of our military forces. We would potentially be complicit in their actions.”

If Mr. Trump’s language is any indication, his rosy-eyed view of the U.S.-Russia friendship is dimming. In January, Trump tweeted “Having a good relationship with Russia is a good thing, not a bad thing. Only ‘stupid’ people, or fools, would think that it is bad!”

But in his address to a joint session of Congress last week, Mr. Trump did not mention Russia once, even when he spoke of plans to “demolish and destroy” ISIS.

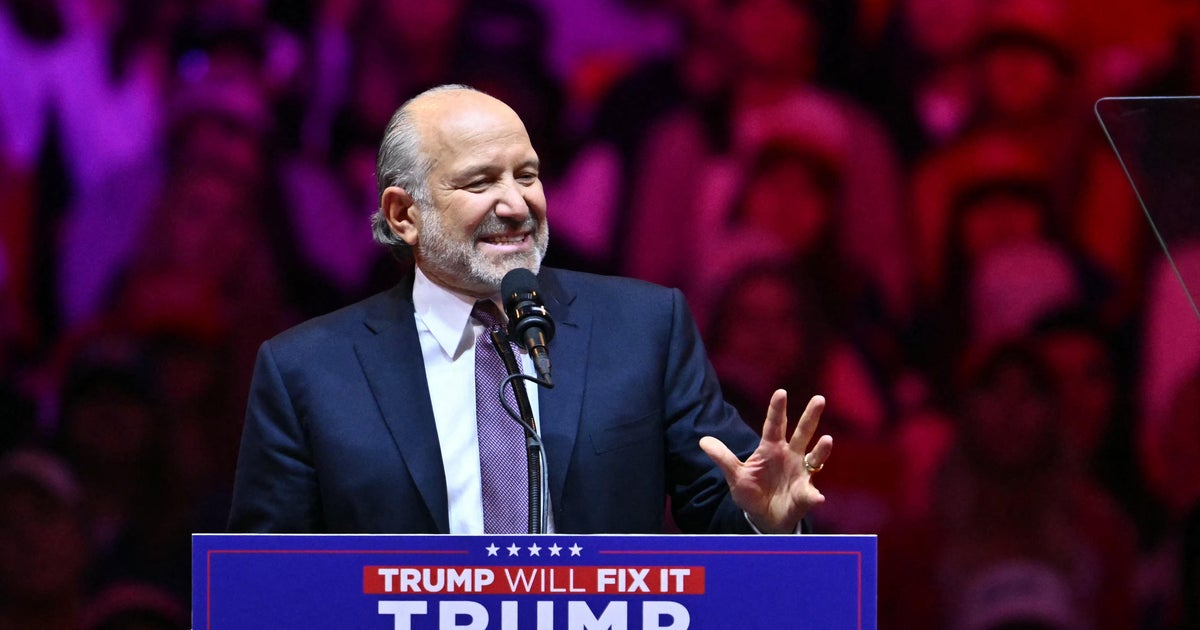

Notably, despite department-wide shakeups, the State Department team in place to counter ISIS has remained untouched. That team did not push Obama to work with Russia in the past. And while the Department of Defense has been the primary drafter of this ISIS plan, Mr. Trump’s new National Security Advisor, Henry McMaster, is widely seen as skeptical of a closer relationship with Russia.

With mounting U.S, frustration towards Russia, the U.S. instead might take on a military greater role in fighting ISIS, explained Gen. Joseph Votel, the commander of American forces in the Middle East, in an interview with CBS News last week.

Votel said that that could “perhaps” mean more American ground troops to fight ISIS, in addition to the hundreds of advisors already there.