Neil Armstrong honored by crewmates and co-workers

Neil Armstrong's crewmates and co-workers honored the first man to walk on the moon during a memorial service at the Johnson Space Center Thursday, recalling the extraordinary competence and quiet dignity that have come to represent the "human face and the human spirit of the Apollo program."

Armstrong died last August at the age of 82 due to complications following surgery. While his life was honored at the time in services at the National Cathedral in Washington and elsewhere, the gathering at the Johnson Space Center was more of a NASA family affair, attended by scores of current and former astronauts, flight directors, flight controllers and engineers.

Also in attendance were his sons Rick and Mark and their mother Janet, Armstrong's wife during the NASA years.

Apollo 11 crewmate Buzz Aldrin, the second man to walk on the moon, told the crowd, "I will be eternally grateful to be so fortunate that my opportunity to fly to the moon and land was under the command of Neil Armstrong, perhaps the best test pilot America's ever seen. And the epitome of a space man."

Crewmate Michael Collins, who remained behind in lunar orbit while Armstrong and Aldrin descended to the moon's surface on July 20, 1969, remembered his commander as "a consummate decision maker" who "took all accolades in his stride and never showed a touch of arrogance, although I think he had plenty of things to be arrogant about."

"He deserved all the good things that came his way," Collins said. "He did this agency proud, he did the whole country proud. For a short time, he did everyone on the globe proud. The whole world applauded our space program and his prominent part in it.

"He was definitely the right choice to be the commander of the first lunar landing," Collins said. "He was the best."

Born in Wapakoneta, Ohio, on August 5, 1930, Armstrong was a naval aviator from 1949 to 1952 and later a test pilot, flying the fabled X-15 rocket plane and other high performance aircraft at Edwards Air Force Base, Calif.

He joined NASA's astronaut corp in 1962 and served as commander of the two-man Gemini 8 mission in 1966, calmly working with crewmate David Scott to stop a stuck thruster that threw the spacecraft into a potentially catastrophic tumble.

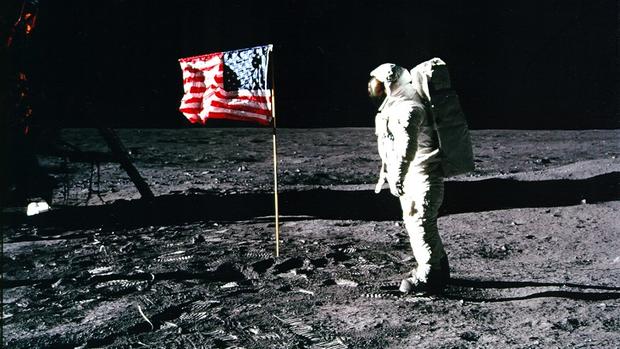

He blasted off a second and final time on July 16, 1969, as commander of Apollo 11, walking into history as the first man on the moon.

Glynn Lunney, a legendary Apollo flight director who went on to serve as NASA's space shuttle program manager, said Armstrong would long be remembered as "the human face and the human spirit of the Apollo program."

"People are going to look back on it in years to come and they're going to be kind of in awe about what got done in those times, and Neil is probably going to be the human focus of that interest," he said.

Lunney said the image many people have of Armstrong today accurately reflects the inner man -- "private, quiet, self disciplined, humble, competent. All those things come to mind. Neil was all that, and he was more."

"Fate just managed to get Neil into position where he was the representative for all of us and for all the space program going forward in time," he said. "We are very lucky, we are very well served that that was the case. God bless you, Neil."

For Gerry Griffin, an Apollo flight director who went on to serve as director of the Johnson Space Center, Armstrong had a unique, hard-to-define ability to capture the essence of an issue, prompting everyone in the room to pay attention.

Griffin said he noticed something different about Armstrong when he first met him in the mid 1960s. Long after the Apollo program ended, Armstrong and Griffin attended a conference at the California Institute of Technology to review the moon program and discuss lessons learned.

"Neil, in his own way, sat there and listened. and finally somebody called on him and he stood up and in about five minutes described how it was we were able to pull off Apollo," Griffin said. "And I noticed when he talked, everyone listened.

"And then it dawned on me, that's what I had seen in 1964, well before he was even assigned to a flight, he had that quality, people listened to him and he had that unique capability to take tough subjects and make them easily understood. That is a quality Neil is very, very unique in, and you can bet every night on a clear moon, I'm going to look at it and wink at him."

Collins briefly addressed Armstrong's post-Apollo life, including his reputation as a recluse and criticism "for being too quiet and not going out and selling the program."

"But by holding to his lifelong yardsticks of honesty, humility and grace, I think he accomplished a lot more than any professional PR man or huckster could have done," Collins said.

Far from being a recluse, Armstrong supported a wide variety of organizations and made numerous public appearances.

"When other Apollo flights were honored, he usually showed up and made very clear that the success of Apollo 11 was due to its predecessors and those that followed," Collins said.

"He went on tours sponsored by the USO to Iraq and Afghanistan. And once he even led cheers at his alma mater, Purdue's, football game. If that's a recluse, I think the nation needs more of them, people who don't seek the limelight but can live competently in its glare, who are the very antithesis of some of today's empty-headed celebrities we seem to admire."

Following the memorial service, a tree was planted in Armstrong's honor at the Johnson Space Center's Memorial Tree Grove, where 48 other deceased astronauts, including the crews of Challenger and Columbia, are remembered.