The lost story of Nearest Green, the slave who taught Jack Daniel how to make whiskey

This piece originally aired Nov. 28, 2017.

There's no mystery about what goes into Jack Daniel's whiskey. The popular drink has been around for 151 years and its recipe is on the company's website. But a story about how Jack Daniel began his distillery is only now gaining attention.

Some of the first clues about the role of Nearest Green were in Daniel's official biography, published in 1967, more than half a century after his death. Green was mentioned about 50 times. Then his name seemed to disappear, until author Fawn Weaver helped uncover the truth at the heart of how Daniel came to make whiskey, reports CBS News correspondent Michelle Miller.

"It's important to set the record straight because anyone who accomplished something like Nearest did should be honored," Weaver said.

What Nearest Green, a slave, did was teach Jack Daniel how to make whiskey.

"It was on the cover of The New York Times international edition. It was possible that an African-American was behind Jack Daniel's. And it's never been spoken about until now?" Weaver said.

For Weaver, finding proof of Green's legacy has become a passion bordering on obsession. Over the past year, Weaver has collected a library of documents, letters and pictures hoping to parse the truth from folklore.

"Finally, one of the elders in the community says, 'Well, you know his name wasn't really Nearest.' Well, his name was Nathan and he's from Maryland," she said.

After digging for over 2,500 hours and speaking to more than 100 relatives, it started to come together.

Debbie Staples – a great-granddaughter of Green's – had heard the tales of whiskey from her grandmother.

"I knew she had no reason to make up a story like that," Staples said.

In the late 1850s, Jack Daniel, an orphan, started working for a wealthy landowner and whiskey distiller named Dan Call. Call teamed Daniel with Green, one of his slaves and his main whiskey man.

"And then after slavery he started his own company and the person he went to first was his mentor, and he did not see race as a barrier," Weaver said.

Weaver soon found evidence in black and white. A1972 article in the Tennessee Historical Quarterly listed Nearest Green as Jack Daniel's first head distiller.

"When we've known and understood the weight of this story, all I can offer is anything we can do to continue to honor the name of Nearest, we will do," said Mark McCallum, president of Jack Daniel's brands.

The company first acknowledged Green as Daniel's mentor last year.

"There was an enormous amount of blowback," McCallum said. "It ranged from some very positive commentary on the story to some very vitriolic. It was a very tense time in America, as well. Then we were into that month or two leading up to the U.S. presidential elections, but I thought the last thing that America needed at that time was for Jack Daniel to come out again after all this commentary and raise up this story again."

"People had been saying this for a very long time, but there was not one shred of proof. And so if you have a story that you know will be controversial because most people don't listen to the whole story," Weaver said.

She says people mistakenly assume, "Jack Daniel had slaves." By all accounts, he did not.

It is believed that Daniel opened his distillery in 1866, a year after the 13th Amendment abolished slavery. Working with Daniel helped to make Green and his children wealthier than many of their white neighbors.

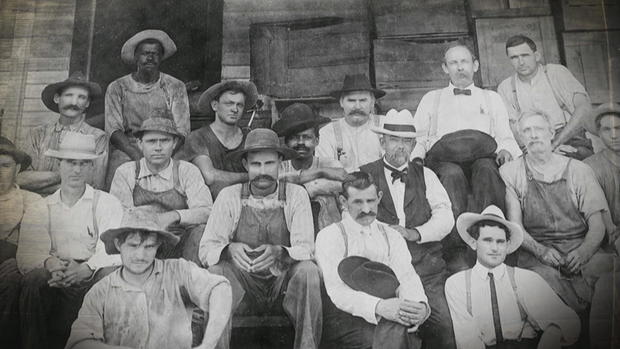

Today, Green is mentioned in tours of the distillery. There is no known photograph of Nearest Green, but there is a picture of Green's son, George, sitting right next to Daniel in a group at a time when black employees were often relegated to the back.

Three living Green descendants still work at the distillery, including his great-granddaughter Debbie Staples.

"It means a lot to me to know that, now the world will know. Our country is divided, I know there is a lot of hate going. But, you know, to be in the South and to have a relationship with someone that's – you would think that would never happen," Staples said.

Despite the deep racial divides of the American South in the 19th century, an improbable friendship brewed – one at the heart of a quintessentially American brand.

"For me, this project ends when I can go anywhere around the world and say 'Nearest Green' and people know who he is. I have never lived in this type of climate of race and when I look at this story, this is one story that's given me hope through everything else," Weaver said.

Weaver hopes to honor Green's legacy by building a memorial park, republishing Jack Daniel's biography, and creating a new whiskey called Uncle Nearest. Proceeds will go toward a scholarship fund for Green's living descendants and to support the Nearest Green Foundation's various efforts.