How Neanderthal DNA may affect our health

Before modern humans drove Neanderthals and other archaic humans to extinction, they interbred with them. These ancient flings, which took place around 50,000 years ago, left their mark on our DNA. Scientists say the genomes of modern-day Eurasians contain about 1.5 to 4 percent Neanderthal DNA. Now a new study seeks to explain what impact that DNA has on the health of modern humans, and whether certain traits may have been bequeathed to us from our prehistoric cousins.

Corinne Simonti, a Vanderbilt University doctoral student, and John Capra, an evolutionary geneticist and assistant professor of biological sciences at Vanderbilt University, and colleagues compared a genome-wide map of Neanderthal haplotypes, or gene groups, with health records and genetic data of 28,000 adults of European ancestry.

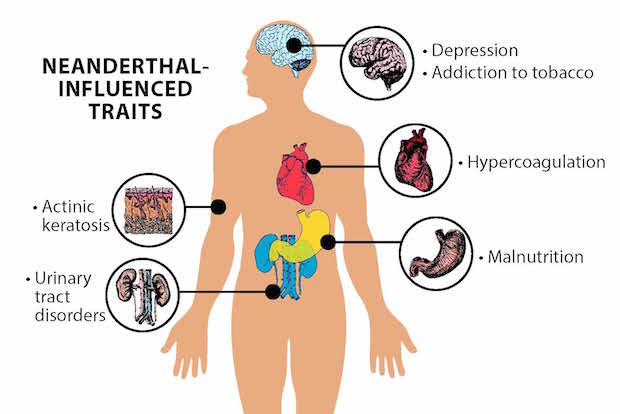

In a study published Thursday in the journal Science, researchers announced that Neanderthal DNA influences a broad range of traits relevant to disease risk in modern humans, including those that influence depression, obesity, mood disorders, skin disease and addiction.

Neanderthal DNA found in modern humans does not cause these conditions directly. But it does influence when and where nearby genes are turned on or off.

"Neanderthal DNA has a small but significant influence on the reported traits and associated disease risk," Capra told CBS News in an email. "Given the complex environmental and genetic causes of most of these diseases, having the associated Neanderthal DNA does not mean that a person is certain to get the disease." In fact, depending on the individual and where the Neanderthal DNA is found along the genome, risk factors could either be increased or decreased.

The Neanderthal DNA that exists in today's population most likely provided modern humans with adaptive advantages 40,000 years ago as they migrated from Africa into other parts of the world with different environmental conditions. However, many of these traits are no longer advantageous in humans.

Take the Neanderthal variant that increases blood coagulation, for example. Researchers suggested that this could have helped our ancestors deal with exposure to new pathogens by clotting wounds more quickly to prevent bacteria from entering the body. Today, however, hypercoagulation increases the risk for pulmonary embolism, stroke and pregnancy complications.

Another Neanderthal-derived genetic variant is associated with tobacco addiction, even though it is clear that Neanderthals did not smoke -- they were extinct thousands of years before tobacco was first introduced in Europe. Capra said that it is possible that this DNA variant had an influence on a related trait that exhibited itself 50,000 years ago.

"This is a great example of how the effects and interpretation of DNA variants are dependent on the environment," Capra said.

Likewise, the study found an association between Neanderthal DNA and depression in modern humans, though Capra said Neanderthals themselves were probably not depressed. "Depression is an incredibly complex disease and we don't fully understand the genetic and environmental drivers of depression today in modern populations. Thus, like nicotine addiction, depression might not even make sense as a 'disease' 50,000 years ago," he explained.

The research also confirmed a previous hypothesis that Neanderthal DNA affects cells called keratinocytes that help protect the skin from UV radiation from the sun. The Neanderthal DNA variant influenced the risk of developing sun-induced skin lesions called keratosis, which are caused by abnormal keratinocytes.

Why wasn't this potentially harmful DNA weeded out in natural selection? The researchers noted that the genetic variants may be beneficial in certain contexts and detrimental in others.

"Many of the diseases we found to be associated with Neanderthal DNA do not exhibit a strong detrimental effect early in life," Capra said. Because there is so little Neanderthal DNA in modern human genomes, researchers suggest that a lot of it was quickly discarded as our species continued to evolve. The bits of Neanderthal DNA that remain, however, can help us to learn about current diseases.

"This study has modern day clinical relevance, because it reveals how evolutionary history has lead to some differences in disease risk between populations," Capra told CBS News in an email. "In terms of treating these diseases, it will be important to understand how these bits of Neanderthal DNA exert their influence at the molecular level."