Navigating our reliance on maps

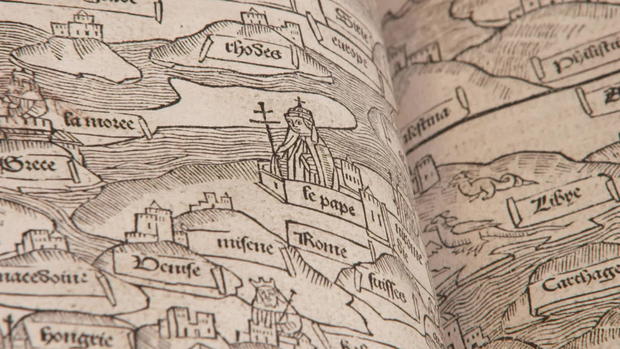

Once upon a time, before maps told us how to get from Point A to Point B, they told us a story. Ian Fowler, who oversees the collection of nearly 800,000 historic maps at the New York Public Library, showed correspondent Martha Teichner an ancient map of the Christian known world: "So, at the top we have these two saintly figures, in this area represented by the Garden of Eden." Also featured on the map: The Pope.

"This isn't north and south?" asked Teichner.

"No. The north and south really does not come for a couple centuries."

As time passes, actual geography begins to show up.

Sixteenth-century maps of North and South America still look peculiar. "We're still getting information from explorers as they come back," said Fowler.

A lot of it wrong, such as California depicted as an island.

And look at poor, squished Michigan:

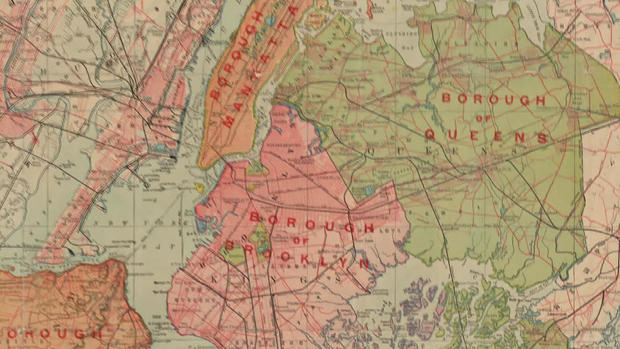

Fast-forward to the 20th century, when Michigan got its revenge. The cars it produced revolutionized maps. "You really didn't get road maps until the advent of the car," said John McAvoy, a vice president of 165-year old Chicago-based Rand McNally. "The very first automobile map they published was of New York City and the vicinity. And they were also the first ones to start numbering roads. The system was later adopted as the model to use across the United States."

Rand McNally published its first road atlas in 1924. By 1999, 75 years later, it had reportedly sold 150 million of them.

That was just about the time the GPOS – the navigational version of the asteroid that killed the dinosaurs – hit us.

Teichner asked science journalist Maura O'Connor, who has written about how we navigate, "In the era of GPS, who needs maps?"

"I think we need maps," she replied. "We don't need maps for everything anymore, but I think if we give them up completely, we'll lose a way of experiencing the world that can give us great pleasure, great satisfaction, can perhaps exercise our hippocampus."

The hippocampus – that use it-or-lose it part of the brain that shapes our spatial perception, our imagination, our memory. Not to scare you, but as O'Connor explained, "When we don't use it, it's being shown to result in a decrease in hippocampal volume, and potentially has some implications for mental health, neurodegenerative disease, and other age-related memory impairments."

Christopher Smith, of Hillsboro, Missouri, is a second-generation trucker and map fan. "My dad handed me his map, and just the way it smelled and the way the pages felt … Now that I got one, it feels exactly the same. It's just really special to me."

He's trying to pass that love on to his own kids. But nostalgia isn't why Smith takes the atlas Rand McNally puts out just for truckers when he goes on the road; it's safety. "I use it to double-check my route on my GPS," he said. "Because a GPS, it's still a machine, it's still fallible."

Or as seen on internet trucker forums, catastrophes captioned by those famous last words: "I was just following the GPS."

So, paper maps not obsolete? Rand McNally maps and atlases are bestsellers still, with more than 400,000 sold so far this year.

For more info:

- Ian Fowler, Curator and Geospatial Librarian, Lionel Pincus and Princess Firyal Map Division, New York Public Library

- Rand McNally

- Rand McNally Road Atlases

- Science journalist Maura [M.R.] O'Connor

- "Wayfinding: The Science and Mystery of How Humans Navigate the World" by M.R. O'Connor (St. Martin's Press), in Hardcover and eBook formats, available via Amazon and Indiebound

Story produced by Robbyn McFadden. Editor: Carol Ross.