Nature up close: Grizzlies and black bears

By "Sunday Morning" contributing videographer Judy Lehmberg.

Both grizzly and black bears were historically found in much of what is now the U.S. and Canada. As humans advanced across North America, grizzly bears have been pushed out of almost all of their former range, but black bears haven't. They can still be found in most of Canada, the Rocky Mountains, the Ozarks, the Northwest, the Appalachians and the Northeast, as well as the mountainous areas of California, Arizona, New Mexico and Texas. They are still in a few pockets in Louisiana, Florida, North Carolina and the Great Lakes as well. Their population is considered stable in most of their range and even increasing in some parts. There are at least 450,000 black bears in Canada, and around that many in the U.S.

No one knows how many there are in Yellowstone National Park. It is known that their population is healthy, and they are much more numerous than grizzly bears, as they reproduce more quickly and don't require large territories. Yellowstone visitors sometimes confuse the two species especially, because some black bears are cinnamon to brown colors. The genetics of black bear fur coloration is not completely understood but is thought to be determined by various combinations of at least several pairs of genes. Their color can range from light cinnamon through various shades of brown to truly black, and some have been known to change color over their lifetime. There is also a population of white black bears in British Columbia, sometimes referred to as spirit or ghost bears.

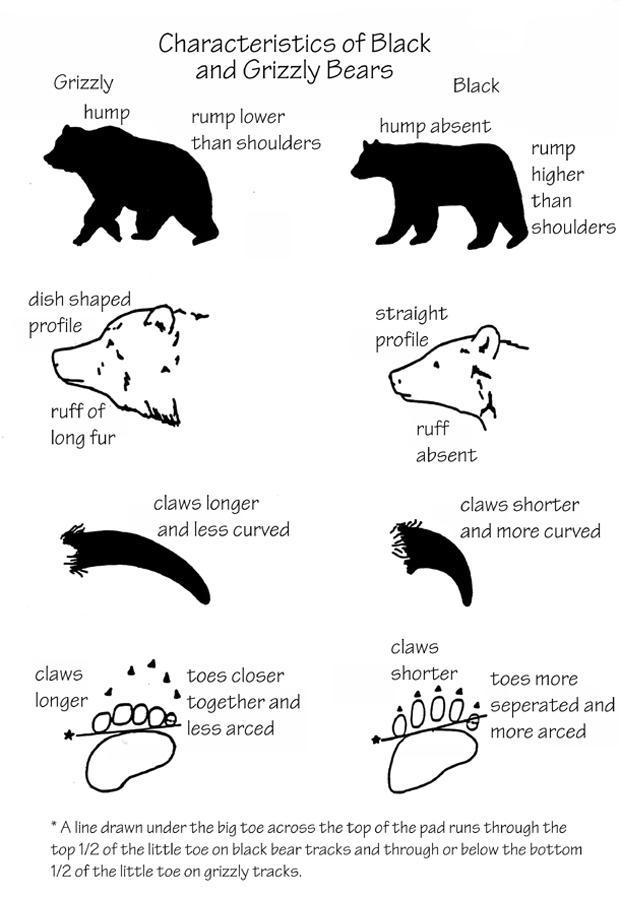

The easiest way to tell a black bear from a grizzly is to look at the shape of its face, whether it has a shoulder hump, and if there is a ruff of fur on the underside of its neck. If you happen to find bear tracks, the species can be differentiated by the angle and shape of their toes (and the generally larger size of a grizzly track).

The above tracks are only the left front foot of each species. The back footprint of both is larger as more of the back foot is in contact with the ground.

One of the more interesting traits of Yellowstone female black bears with cubs is they will purposefully stay near roads and therefore crowds of people. It is believed they do that, especially during May and June (which is bear mating season) to avoid "back country" males who will normally not come near a road with people on it. They need to avoid those males who will try to kill their cubs so they will come into estrus and be willing to mate. Even so, new cubs are lost every year to males wanting to mate.

Like grizzlies, black bears are omnivorous, although both of their digestive systems are more similar to a carnivore's, as they are both in the Order Carnivora. The one difference between them and other carnivores is their digestive system is longer, giving them more time to digest and absorb plant nutrients, which make up a large percentage of their diet. Most of the black bears we see are eating grass, dandelions and clover, as well as berries when they ripen.

In the fall bears go into hyperphagia in an attempt to add as much fat as possible so they can survive the long months of hibernation. In Yellowstone one of their main fall foods is white-bark pine seeds. As climate change continues to affect Yellowstone, more white-bark pine trees are dying from white pine blister rust, pine beetle outbreaks and wildfires. The former two have become more numerous due to higher winter temperatures (cold temperatures are necessary to kill back both blister rust fungi and pine beetles), and wildfires have increased with warmer, drier conditions. In fact, one half of all the white-bark pine trees in the Rocky Mountains have died due to a combination of the above three factors, and are dying at a much faster rate than young trees can replace them. Because of their decline there are not always enough seeds to sustain the black bears, as well as the other species dependent upon them.

Black bears do have one advantage: they are willing to eat a wide variety of foods. When they are ready to begin hibernation, usually in November, they move up on a north-facing slope to between 5,800 and 8,600 feet. They either find an old den or dig a new one. Since black bear females keep their cubs for a year they all hibernate together, while single females and males den alone.

It is especially important that pregnant females gain a significant amount of weight in the fall prior to hibernation, usually around 150 pounds. Their reproductive strategy involves delayed implantation. They mate in June. If an egg is fertilized it divides for a short period of time until it is an undifferentiated blob of cells and then stays in a state of suspended animation for five to six months. If the female bear has gained enough weight that blob of cells, the blastocyst, implants in the uterine wall and begins to grow. Actual embryological development only takes two months from the time of implantation in late November to early December to birth in late January to early February.

The tiny cubs are born blind and hairless. During hibernation the female's fat cells are chemically changed into milk so the cubs can nurse, in-between sleeping, for two to three months, during which time their mom obviously eats nothing. She and her new cubs emerge from their den in March or April, usually later than the single bears.

Judy Lehmberg is a former college biology teacher who now shoots nature videos.

For more:

- Judy Lehmberg (Official site)

- Judy Lehmberg's YouTube Channel

To watch extended "Sunday Morning" Nature videos click here!