Nature up close: Masters of long-distance flight

By "Sunday Morning" contributing videographer Judy Lehmberg.

One of the advantages of being a photographer is getting to go to some great places. Another advantage is hearing from my photography friends when they go to great places. For the last two months my friend Sherri O'Brien has been in Alaska, one of the literal hot spots of climate change this summer, with abnormally high temperatures, drought, extensive fires and lots of melting ice.

But Sherri has managed to see some great animals in spite of the smoke and heat. One of the birds she was lucky enough to find was the world's longest-migrating animal, the Arctic tern.

Sherri found Arctic terns nesting in Valdez, Alaska, along a harbor. As she approached them she was immediately dive-bombed by several protective parents. It was only then she realized there were eggs and young chicks well-camouflaged in the gravel. She quickly retreated, not wanting to stress the birds, and took photos from her truck.

The terns still sitting on eggs took turns keeping the eggs warm while their mates fished, and then switched places. The females guarded the newly-hatched chicks while the males brought in fish which they regurgitated for them. But sometimes the females got tired of waiting and went and caught their own fish.

No one knows why, but terns nest in the Arctic, during the Arctic summer, and then they fly all the way to Antarctica to spend a second summer there. Because they summer in both the Arctic and the Antarctic, they spend a greater percentage of their life in sunlight than any other species on Earth.

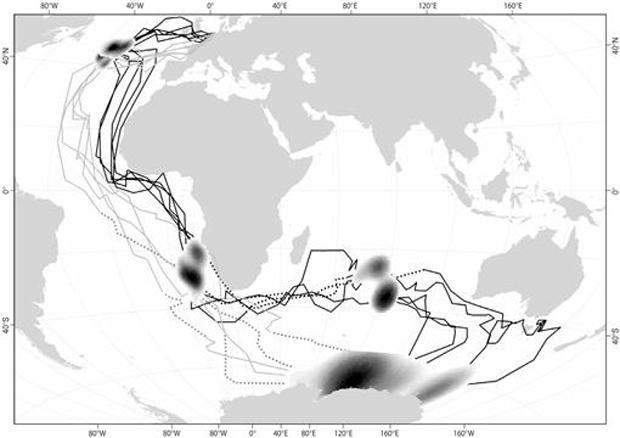

Scientists have known for a good while that Arctic terns fly further every year than any other animal, but it wasn't until fairly recently that they realized just how far they fly. Now, through the use of tracking devices, we know what we thought was a 24,000-mile round trip (the distance between the Arctic and the Antarctic) is actually more than 55,000 miles, because terns don't fly in a straight line.

One group of Arctic terns in the Netherlands was recently fitted with extremely lightweight tracking devices and followed for several years. On their way south they followed the European and African coastlines, but when they got to the southern tip of Africa they turned east, flew about halfway to Australia and then turned south again to the Antarctic. On their way back north they flew northeast, until they got to the coast of Namibia, where they turned to the northwest, crossed the Equator and continued northwest until they got close to the Caribbean. Then, they turned back to the northeast until they reached their breeding grounds in the Netherlands. Their migration pattern, in the shape of a large "S," is logical considering the prevailing winds are counter-clockwise in the South Atlantic and clockwise in the North Atlantic. This pattern also allows them to stop along the way at several high-nutrient hotspots in the central North Atlantic and along the polar front, where colder, more productive waters meet warmer, less productive waters in the southern hemisphere, for much-needed refueling.

Although Arctic terns, with a length of 12 inches and a weight of slightly under 4 ounces, are not large birds, they are superb fliers with a keen ability to glide for extended periods of time. They can even sleep as they glide. Long glides are possible because they have a high wing aspect ratio; that is, their wings are long and thin, like an albatross, rather than short and wide, like a hawk.

They also live a long time. Fifty percent of them live longer than 30 years. That means in an average lifetime they will fly more than 1,500,000 miles – that's the distance to the moon and back three times over.

Judy Lehmberg is a former college biology teacher who now shoots nature videos.

For more:

- Judy Lehmberg (Official site)

- Judy Lehmberg's YouTube Channel

To watch extended "Sunday Morning" Nature videos click here!