Nature up close: An unexpected gem of a museum

By "Sunday Morning" contributing videographer Judy Lehmberg.

My husband jokes that, as a biologist and general wildlife lover, I'm only interested in something if it has four legs and a tail. And he is pretty much right – it has to be really special to draw my interest away from anything living. One special place is the New Mexico Mineral Museum, a crystal palace of mineral specimens on the campus of New Mexico Tech in Socorro, N.M.

Biologists are interested in living things mostly on the surface of the Earth; geologists think of plants and animals as the obstructions that get in their way when they want to get to the "good stuff" – the rocks and minerals that make up our Earth.

We've been coming to the Socorro area for years because of nearby Bosque del Apache National Wildlife Refuge and its large populations of wintering sandhill cranes, snow geese and ducks. Our first trip to the area was in the early 1980s when a New Mexico Tech recruiter invited us to bring our students during a six-week summer field trip in environmental science and plant taxonomy. The trip took us through New Mexico, the Grand Canyon, Arches, the Tetons and finally Yellowstone. The students learned the same basic information as they would on campus, but the lab activities and examples we could show them were obviously more real-life.

One of the highlights of our New Mexico Tech tour was a visit to a real mine, where we even got to collect some samples. I still have mine on our fireplace.

We are currently camped right next to Bosque del Apache, with Socorro only a few minutes to the north. The bird activity is a little slow in the middle of the day, so we decided to visit the mineral museum. I hadn't been there in years and had forgotten just how exquisite their collection is. Luckily, I was able to see it with Bob Eveleth, Senior Mining Engineer Emeritus, who reintroduced me to the collection with his extensive knowledge and enthusiasm.

Minerals are inorganic compounds formed by geological processes with an ordered atomic structure. Professional mineralogists describe about 30 new minerals each year, adding to the more than 5,000 already classified. Their crystal structure and chemical composition are the basis of the classification.

Diamonds and graphite are good examples. Both are composed of pure carbon, but their crystal structures are dissimilar, leading to very different physical properties (and prices). Diamonds are the hardest abrasives known, while graphite is an excellent lubricant.

Most of the Earth's crust is crystals, except the molten parts. Mineral crystals form when elements or compounds in solution, either molten or dissolved in water, come out of solution and solidify. Salt and gypsum simply precipitate when water bearing these compounds evaporates, leaving the crystals behind. Some crystals, notably sulfur, can form from vapor as it condenses.

For example, silicon dioxide (SiO2), can be formed in several ways, either as molten igneous material cools or hardens, or as water-bearing silica percolates through other rock. Igneous quartz, like rose quartz, is one of the minerals found in granite, a mixture of minerals that cools underground and precipitates out its different minerals. The slower the molten material cools, the larger the crystals grow. Sedimentary quartz is often formed when superheated silica-bearing water passes through rock. If the minerals precipitate in a rock cavity, beautiful crystals can grow slowly, over literally thousands, even hundreds of thousands of years.

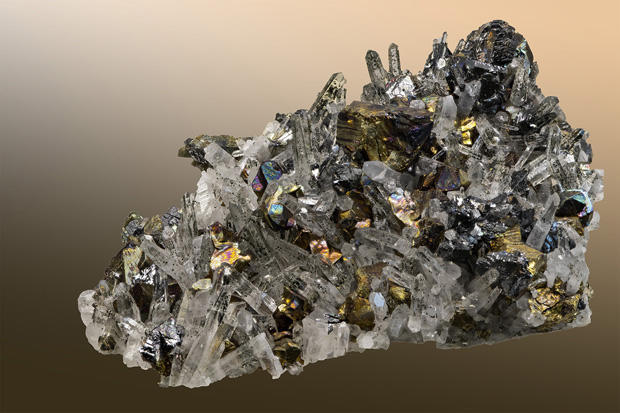

Many of the crystals in the mineral museum collection were formed in the Earth hydrothermally. The variation of mineral mixtures in the water, as well as temperature, generates most of the 5,000 or so different minerals.

Which minerals are deposited depend on how deep in the Earth they formed and how hot the water was. Quartz, fluorite, topaz, gold, galena, pyrite and chalcopyrite formed deep in the Earth at temperatures between 300 and 500 degrees Celsius. Slightly cooler temperatures, between 200 and 300 degrees C, also produce pyrite and quartz, as well as calcite, opal and some carbonate minerals. At shallow depths and water temperatures (between 50 and 200 C), quartz is again deposited, such as silica in petrified wood, along with cinnabar, dolomite and fluorite.

The Socorro, New Mexico region is famous for the Smithsonite found around Magdalena Mountain, a towering formation west of town. Some of the minerals we saw so many years ago on our mine tour, in the Magdalena District, are on display in the museum, including several color variations of Smithsonite.

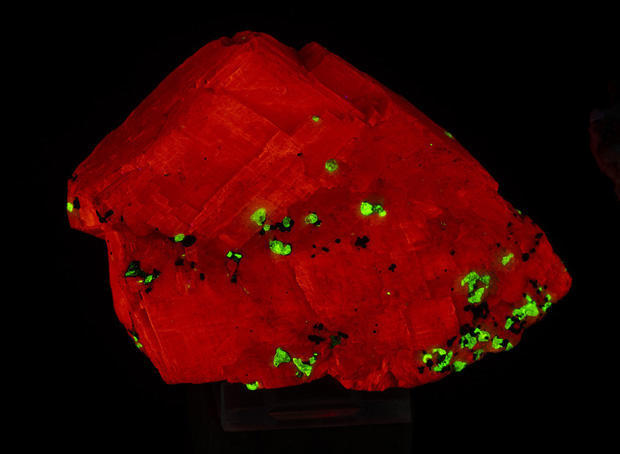

Some minerals can absorb light at one wavelength, such as short-wave ultraviolet light, and reemit it as visible light. Shining a UV light on these minerals produces a vivid array of orange, red and green light in return. As soon as the UV is turned off, the visible light disappears as well. Other compounds are phosphorescent. Once they are irradiated with UV, the light can be turned off and they will continue to give off visible colors for a while. Electrons in the elements are excited by UV light, jump to a higher energy state, then give off visible light as the electrons slowly drop back to their original ground state. Examples of phosphorescent mineral include calcite, fluorite, willemite and sphalerite.

The museum is open Monday to Friday, 9 a.m. to 5 p.m., and on Saturday and Sunday from 10 a.m. to 3 p.m. More information is available on their website, at geoinfo.nmt.edu. (A special thank you to museum curator Kelsey McNamara for arranging my tour.)

Judy Lehmberg is a former college biology teacher who now shoots nature videos.

See also:

- Judy Lehmberg (Official site)

- Judy Lehmberg's YouTube Channel

To watch extended "Sunday Morning" Nature videos click here!