NASA's Kepler closing in on Earth-like exoplanets

Slowly but surely closing in on an answer to a fundamental question -- how common are Earth-like planets orbiting sun-like stars? -- NASA's Kepler space telescope has discovered the smallest worlds yet found orbiting in or near the habitable zones of two distant suns, researchers announced Thursday.

While all three planets are larger than Earth, they are the closest analogues yet found orbiting in the region around their parent stars where water could exist as a liquid, a critical necessity for the evolution of life as it is currently understood.

"We are on the verge of the discovery of so many very exciting planets that, in turn, will tell us so much more about how rocky planets work, how they can be diverse and we will then learn something as well for our own Earth," Lisa Kaltenegger a researcher with the Max Planck Institute for Astronomy and the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, told reporters.

In a statement, John Grunsfeld, NASA's associate administrator for space science, said "the discovery of these rocky planets in the habitable zone brings us a bit closer to finding a place like home."

"It is only a matter of time before we know if the galaxy is home to a multitude of planets like Earth, or if we are a rarity," he said.

The hunt for exoplanets is one of the hottest fields of astronomical research with international teams using ground-based telescopes and spacecraft to search for the subtle dimming of a star's light or the slight wobble that occurs as unseen planets swing around in their orbits.

Launched in 2009, the Kepler space telescope is equipped with a 95-megapixel camera that that continually monitors the light from more than 150,000 stars in a patch of sky in the constellation Lyra.

Planets passing in front of targeted stars cause a very slight, periodic dimming. By timing repeated cycles, computer analysis can ferret out new worlds, including potential Earth-like planets orbiting in a star's habitable zone where water can exist as a liquid.

Prior to Thursday's announcement, NASA's Exoplanet Archive listed 844 confirmed planets orbiting 658 stars, including 128 solar systems hosting multiple planets. The Kepler spacecraft had discovered 115 confirmed planets and 2,740 planet candidates requiring additional observation and analysis.

Up to this point, Kepler had found just two planets in the habitable zones of their parent stars and both of them were considerably larger than Earth.

But the spacecraft's latest discoveries include seven confirmed planets in two solar systems, including the smallest worlds yet found in a star's habitable zone.

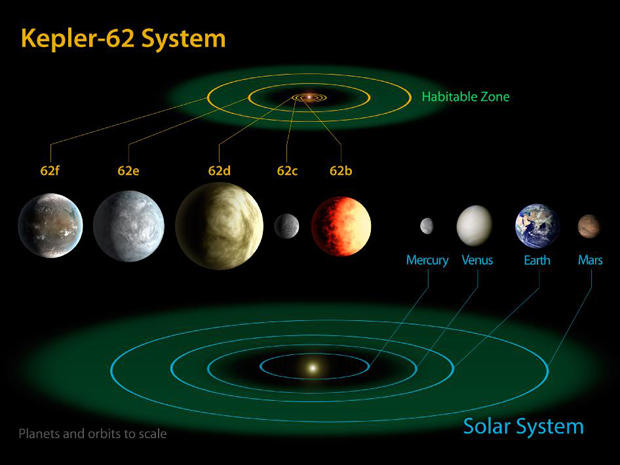

A star known as Kepler-62 hosts five known planets, including two that orbit in the habitable zone, while a star known as Kepler-69 hosts at least two worlds, including one on the inner edge of its habitable region.

Kepler-62, at a distance of 1,200 light years from Earth, is roughly two-thirds the size of the sun and only one-fifth as luminous. Two of its five planets -- Kepler-62e and Kepler-62f -- are so-called super-Earths with a radius of 1.6 and 1.4 times that of Earth respectively.

Kepler-62e orbits its sun every 122 days while Kepler-62f, just 40 percent larger than Earth, completes a year every 267 days.

"This appears to be the best example our team has found yet of Earth-like planets in the habitable zone of a Sun-like star," said Alan Boss, a Kepler researcher at the Carnegie Institution and a leading theorist in planetary evolution.

A star known as Kepler-69, located some 2,700 light years away, is 93 percent the size of the sun and 80 percent as luminous. It hosts two confirmed planets, Kepler-69c and Kepler-69b.

The former is 70 percent larger than Earth, but it orbits near the inner edge of the habitable zone, much like Venus in Earth's solar system, taking 242 days to complete a year. This is the smallest planet yet found in the habitable zone of a sun-like star.

Kepler-69b is more than twice as large as Earth and orbits so close to its sun that it completes a year every 13 days.

While the two solar systems do not precisely mirror Earth's, they illustrate a trend in the Kepler data -- with more and more observations, astronomers should be able to identify smaller, more Earth-like planets to determine how rare, or common, they might be.

"We only know of one star that hosts a planet with life, the sun," Thomas Barclay, a Kepler researcher, said in a statement. "Finding a planet in the habitable zone around a star like our sun is a significant milestone toward finding truly Earth-like planets."