NASA is working with SpaceX and Blue Origin to land U.S. astronauts back on the moon

A small robotic lander built by a private company and carrying a scientific payload for NASA touched down near the south pole of the moon 11 days ago… and promptly tipped over on its side. Even so, it's the first American spacecraft to land on the moon in more than 50 years.

NASA has a much more ambitious lunar program - called Artemis – which aims to send people back to the moon, to establish an outpost at the south pole, and to push on from there to Mars.

We previewed Artemis here in 2021, but there are significant questions now about the program's costs and its timetable. In January NASA announced its new target for a manned landing - late 2026 - a year later than planned. but as we discovered, even that may be unrealistic.

When Artemis I soared into space in November of 2022, it was the beginning of a nearly flawless mission. In its first test flight, NASA's new space launch system rocket sent an empty Orion crew capsule on a 1.4 million mile flyby of the moon before a picture-perfect return to Earth.

The next flight – Artemis II - meant to carry four astronauts on a lunar flyby – was supposed to launch this year, and then a year later Artemis III would land the first woman and first person of color on the moon. It's not working out quite that way.

George Scott: I think it is safe to say, without significant reductions in cost, better cost controls, better planning, this Artemis program on its current trajectory is not sustainable.

George Scott is NASA's acting inspector general. Don't be misled by the 'acting'; he's been a top agency watchdog for more than five years. While NASA's engineers have their heads in the stars, it's his job to bring them back to Earth, particularly when it comes to costs.

George Scott: Right now, we're-- we're estimating that per launch-- the Artemis campaign will cost $4.2 billion per launch.

Bill Whitaker: Per launch?

George Scott: Per launch. That's an incredible amount of money per launch. A lot of that hardware is just going to end up in the ocean, never to be used again.

Bill Whitaker: The-- inspector general for NASA says that the costs for the Artemis program are simply unsustainable. Is he wrong?

Jim Free: We didn't necessarily agree with their conclusions. We, we feel like we've taken an affordable path to do these missions.

Jim Free is NASA's associate administrator, and directly in charge of Artemis. We met him at historic Launch Pad 39b, from which both Apollo and Artemis rockets have flown.

Jim Free: We believe that the rocket we have is best matched for the mission and frankly the only one in the world that can take crews to the moon.

But as George Scott said, most components of that SLS rocket end up in the ocean; they're not reusable. And with the goal of building an outpost on the moon, Artemis will need a lot of those $4.2 billion rockets!

Bill Whitaker: It's going to take launch after launch after launch to get all that stuff up there.

Jim Free: Yes. So the number of launches is daunting. But it's-- it's hard to get people to the moon.

When America sent Neil Armstrong and 11 more astronauts to the moon a half century ago, they got to the lunar surface aboard landers…owned and operated by NASA.

Bill Whitaker: You're taking a different approach this time than with Apollo. What's-- what's the difference this time?

Jim Free: The difference is we're buying it as a service. We're paying someone to take our crews down and take them up.

That someone is Elon Musk. In 2021, NASA signed a nearly $3 billion contract with his SpaceX to use its new Starship mega-rocket as the lunar lander for the first Artemis astronauts.

SpaceX is preparing for its third Starship launch atop its enormous super-heavy booster. The first two launches both ended in roughly the same way.

Announcer (during SpaceX broadcast): As you can see, the super-heavy booster has just experienced a rapid unscheduled disassembly.

"Rapid unscheduled disassembly" is SpaceX-speak for "our Starship rocket just blew up," again.

Bill Whitaker: And now you've seen some of the perils of relying on SpaceX.

Jim Free: We've seen some of the challenges they've had on Starship. We need them to launch several times-- to give us the confidence that we can put our crews on there.

Bill Whitaker: But right now, as we sit here today, you have no way of getting the astronauts to the surface of the moon because of these problems that SpaceX has faced?

Jim Free: Because they haven't-- they haven't hit the technical milestones.

SpaceX's stated plan is to first put its Starship lander into low earth orbit, then launch 10 more starship tankers to pump rocket fuel into the lander in space…

… before sending it onward to meet astronauts in lunar orbit.

Bill Whitaker: And this has never been done before?

Jim Free: There's been small-scale transfers in orbit, but not of this magnitude.

Bill Whitaker: It just sounds incredibly complicated.

Jim Free: It-- it is complicated. There's no doubt about that. It's d-- you don't-- you just-- just launch ten times kind of on a whim.

George Scott: If it's never been done before, chances are it's going to take longer than you think to do it, and to do it successfully, and-- and prove that technology before we trust putting humans on it. There is a long way to go.

NASA's contract with SpaceX requires the company to make an un-manned lunar landing with Starship before trying one with astronauts on board. But NASA still says the manned mission can happen in two and a half years.

Bill Whitaker: And that just seems like the time frame we're talking about, the end of 2026, seems ambitious to say the least.

Jim Free: What we're doing is ambitious And it's a great goal to have. To do that--

Bill Whitaker: Is the goal realistic?

Jim Free: I believe it is. I-- I believe it is.

Jim Free's optimism is based on SpaceX's track record with its smaller Falcon rocket.

Once it got the Falcon up and running, it demonstrated it can launch a lot – 96 times last year alone, with both commercial and government payloads. But so far Starship has yet to reach orbit even once.

Bill Whitaker: Does that concern you, that that's going to keep pushing that timeline back further--

Jim Free: Of course it absolutely concerns me because we need them to launch multiple times.

SpaceX ignored our multiple requests for an interview or comment. But in an interview with "The Daily Wire" in January, Elon Musk said this:

Elon Musk (in "Daily Wire" interview): We're hoping to have first humans on the moon in less than 5 years.

Jim Free: My view of that is we have a contract with SpaceX that says they're going to launch our crew in the end of 2026.

Why does it really matter when we get back to the moon? Here's why: China has said it plans to send its "taikonauts" to the moon by the end of the decade, and NASA Administrator Bill Nelson has publicly expressed concern.

Bill Nelson (during 8/8/23 briefing): Naturally, I don't want China to get to the South Pole first with humans and then say, "This is ours, stay out."

To ensure that the U.S. will plant its flag first, NASA signed a new $3 billion contract last year with Blue Origin, the space company owned by billionaire Jeff Bezos, to build another lunar lander. And Jim Free is crystal clear that he sees it as an option if SpaceX Starships keep blowing up.

Jim Free: If we have a problem with one-- we-- we'll have another one to rely on. If we have-- a dependency on a particular aspect in-- in SpaceX or Blue Origin and it doesn't work out, then we have another lander that can take our crews.

In this battle of the star-gazing billionaires, Bezos' Blue Origin has far fewer launches than Musk's SpaceX, and has been far quieter about its ambitions… until now.

John Couluris: So what we're looking to do is not only get to the moon and back, but make it reliable, and repeatable, and low cost.

John Couluris's title at Blue Origin is "senior vice president of lunar permanence," and it says a lot about the company's ambition.

John Couluris: The landers that Blue Origin's going to be building are reusable. We'll launch them to lunar orbit. And we'll leave them there. And we'll refuel them in orbit, so that-- multiple astronauts can use the same vehicle back and forth.

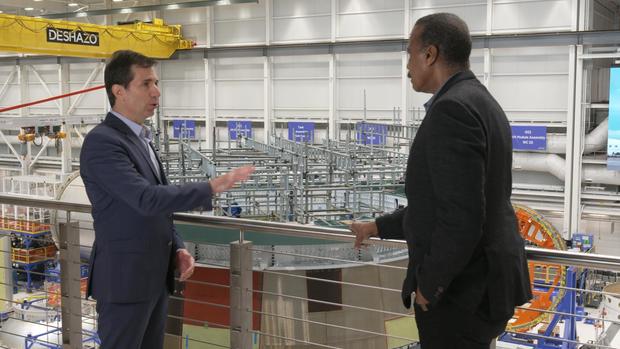

Our cameras were among the first to be allowed inside Blue Origin's huge complex in Florida, just next to Kennedy Space Center.

Bill Whitaker: This is where the future is being built.

John Couluris: That's right. This is the main factory floor for the New Glenn rocket.

New Glenn is Blue Origin's first heavy lift rocket. Its maiden launch will be sometime this year.

John Couluris: So you can see over here we have three different second stages already in build here.

The first New Glenn is already out at Blue Origin's launch complex. It's designed to carry all sorts of payloads, including the lunar lander being built for NASA.

John Couluris: So this is the Mark 1 lander. We call this our small lander.

Bill Whitaker: This is the small one?

John Couluris: Yes.

It's actually a mock-up of their cargo lander, in Blue Origin's Florida lobby. John Couluris used to work at SpaceX, and he came over to Blue to help speed things up.

Bill Whitaker: Is there a bit of a space race between you and SpaceX?

John Couluris: So the country needs competition. We need options. Competition brings innovation.

Bill Whitaker: But you haven't had anything close to the accomplishments that SpaceX has had at this point, have you?

John Couluris: SpaceX has done some amazing things. And they've changed the narrative for access to space. And Blue Origin's looking to do the same. This lander, we're expecting to land on the moon between 12 and 16 months from today.

Bill Whitaker: 12 and 16 months from today--

John Couluris: Yes. Yes. And I understand I'm saying that publicly. But that's what our team is aiming towards.

Bill Whitaker: But that's for, that's for the cargo lander. What about humans?

John Couluris: For humans, we're working with NASA on the Artemis V mission. That's planned for 2029.

That's not so different from Elon Musk's forecast of when SpaceX can land humans back on the moon… even if it doesn't match NASA's. Like the Starship, Blue Origin's lander will require in-space re-fueling, but Couluris insists that it and their rocket will help NASA trim costs.

John Couluris: Our New Glenn vehicle will be-- a reusable vehicle from its first mission. That lander for the astronauts is a reusable lander. So now you're not just taking the equipment and throwing it away. You're reusing it for the next mission.

Bill Whitaker: You do it again, and again, and again. Is that where the cost savings comes in?

John Couluris: Exactly. We are now building with NASA, the infrastructure to ensure lunar permanency.

Bill Whitaker: You have said that the Artemis program is the beginning, not the end. Tell me, what is the future you see?

Jim Free: I see us landing on Mars. Absolutely see us landing on Mars. But we have to work through the moon to get to mars.

Bill Whitaker: These are magnificent goals, you know, going back to the moon, going to Mars. Do we have the ability to do what we're dreaming of doing?

George Scott: You know, this is NASA. Right? This agency is destined to continue to do great things. There's no question about that. What we're telling the agency is, "Just be more realistic." There's nothing wrong with being optimistic. In fact, it's required. Right? In this business, optimism is required. The question is though, can you also be more realistic?

Produced by Rome Hartman. Associate producer, Sara Kuzmarov. Broadcast associate, Mariah B. Campbell. Edited by Craig Crawford.