NASA studies adding crew to super rocket test flight

NASA managers said Friday they hope to know within a month or so whether it might be feasible -- or advisable -- to put two astronauts on board the first test flight of a huge 322-foot-tall Space Launch System super booster scheduled for its maiden launch late next year.

The study, requested by the Trump administration, already is underway, but William Hill, deputy associate administrator for Exploration Systems Development at NASA Headquarters, said major technical challenges will need to be resolved, and the agency will need more money to make it happen.

“It’s going to take a significant amount of money, and money that will be required fairly quickly to implement what we need to do,” he told reporters. “So it’s a question of how we refine the funding levels and the phasing of the funding for the next three years and see where it comes out.”

If the feasibility study doesn’t pan out, he said, “we still have a very exciting mission.”

The current plan calls for launching a “Block 1” SLS rocket in late 2018 -- Exploration Mission 1, or EM-1 -- to boost an unpiloted Orion capsule on a three-week flight beyond the moon and back to a high-speed re-entry and splashdown.

EM-2, featuring an astronaut crew, would be launched atop a Block 1B SLS rocket in the late 2021 timeframe. Unlike the EM-1 rocket, the Block 1B version of the SLS would feature a more powerful, human-rated “exploration upper stage,” or EUS.

The long-range plan, with its roots in the Obama administration, is to use the SLS to send astronauts beyond the moon in the mid-2020s, first to rendezvous with a robotically retrieved asteroid, or chunk of an asteroid, and then to orbit Mars in the 2030s.

The long gap between the SLS’ initial test flight and the piloted EM-2 mission, driven in large part by NASA’s budget and a variety of technical hurdles, has raised concerns in some quarters about maintaining public and congressional support in a program with years between flights and competing demands on agency funding.

President Trump’s transition team asked NASA to look into the possibility of either moving EM-2 earlier or adding astronauts to EM-1. Hill said the latter option was more realistic than the former because of major infrastructure modifications that will be needed to support the larger Block 1B SLS.

But there are major technical challenges with speeding up Orion development for an earlier-than-panned human mission.

“We know there are certain systems that needed to be added to EM-1 to add crew,” said Bill Gerstenmaier, director of space operations at NASA Headquarters, including a life support system, a waste management system, operational cockpit displays and an operational abort system, all big-ticket items.

In addition, the interim upper stage used by the Block 1 SLS is not certified for human flights. While a similar stage has flown flawlessly atop Delta 4 rockets, additional tests would be required and procedures put in place to ensure crew safety if a malfunction occurs.

“So we have a good, crisp list of all the things we would physically have to change from a hardware standpoint,” Gerstenmaier said. “Then we asked the team to take a look at what additional tests would be needed to add crew, what the additional risk would be, and then we also wanted the teams to talk about the benefits of having crew on the first flight.”

The risk-benefit trade will be a crucial element of the review. NASA’s Aerospace Advisory Panel met Thursday, and in a statement, chairwoman Patricia Sanders cautioned the agency not to pursue an early piloted mission without strong technical justification.

“NASA should provide a compelling rationale, in terms of benefits gained in return for accepting additional risk, and fully and transparently acknowledge the tradeoffs being made,” she said. “If the benefits warrant assumption of additional risk, we expect NASA to clearly and openly articulate their decision process and rationale.”

In a Feb. 17 memo to agency employees, acting Administrator Robert Lightfoot raised the possibility of adding astronauts to Exploration Mission-1.

“I know the challenges associated with such a proposition, like reviewing the technical feasibility, additional resources needed, and clearly the extra work would require a different launch date,” he wrote. “That said, I also want to hear about the opportunities it could present to accelerate the effort of the first crewed flight and what it would take to accomplish that first step of pushing humans farther into space.”

The SLS-Orion missions, “coupled with those promised from record levels of private investment in space, will help put NASA and America in a position to ... ensure this nation’s world preeminence in exploring the cosmos,” he wrote.

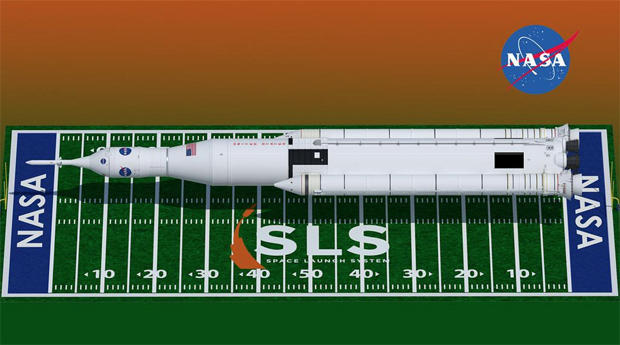

In its initial configuration, the SLS Block 1 rocket will be made up of two shuttle-heritage five-segment solid-fuel boosters provided by Orbital ATK and a huge first stage powered by four hydrogen-burning RS-25 space shuttle main engines built by Aerojet Rocketdyne.

The Block 1 version features an interim upper stage derived from Boeing’s Delta 4 rocket powered by a single hydrogen-fueled Aerojet Rocketdyne RL-10B2 engine.

Even in its initial configuration, the giant SLS rocket will generate a ground-shaking 8.8 million pounds of thrust -- 15 percent more than NASA’s legendary Saturn 5 moon rocket -- enough to boost the 5.75 million-pound rocket out of the dense lower atmosphere. Together with the second stage engine, the SLS Block 1 will be able to put 154,000 pounds into low-Earth orbit.

NASA eventually plans to build a Block 2 version of the SLS featuring advanced strap-on boosters with a liftoff thrust of 9.2 million pounds.

Gerstenmaier said the agency was not under any political pressure to put astronauts aboard EM-1, saying “this is something we’ll go evaluate and ... we’ll see what the results look like coming out the other side.”

But it will not be easy. To convert the EM-1 Orion into a piloted version, life support and other critical systems will be required, along with extensive testing, adding to the mission’s price tag and inevitably delaying the flight. The flight would be limited to two astronauts on a free-return trajectory around the moon lasting eight to nine days.

Gerstenmaier said if the study shows the Orion spacecraft cannot be prepared for flight before the end of 2019 it likely would make more sense to stick with the original timeline and fly EM-1 uncrewed.

NASA’s current deep space exploration program has its roots in presidential politics and agendas dating back to the shuttle Columbia’s destruction during re-entry in 2003.

In the wake of the disaster, the Bush administration directed NASA to finish the International Space Station and retire the shuttle by the end of the decade and to focus instead on building new rockets and spacecraft for a return to the moon in the early 2020s. Antarctica-style moon bases were envisioned as both a science initiative and as stepping stones to eventual flights to Mars.

NASA came up with the Constellation program and began designing a new Saturn 5-class super rocket to boost lunar modules and habitats to the moon, along with a smaller rocket to carry astronauts to low-Earth orbit. The crew capsule was called Orion and the plan was to link up with the lunar lander/habitat in Earth orbit and then head for the moon.

After the 2008 presidential campaign, President Obama ordered a review of NASA’s human space program. A presidential panel concluded Constellation was over budget and unsustainable, suggesting instead that NASA adopt a “flexible path” architecture, bypassing the moon in favor of a manned flight to an asteroid and an eventual flight to orbit Mars.

The Obama administration’s Office of Science and Technology Policy ultimately approved a two-tiered approach to human spaceflight. It retained the Constellation program’s Orion capsule, built by Lockheed Martin, and ordered NASA to build a single large rocket -- what became the Space Launch System -- for deep space exploration.

At the same time, the agency has awarded contracts to Boeing and SpaceX to develop piloted spacecraft, on a commercial basis, to ferry astronauts to and from the International Space Station. The idea is to encourage private industry to develop low-Earth orbit while NASA focuses on deep space exploration.

More recently, the Obama administration specified an asteroid retrieval mission to robotically haul a small asteroid, or part of one, back to the vicinity of the moon for hands-on exploration by astronauts aboard an Orion spacecraft. Such missions would set the stage for an Orion, attached to a habitation module of some sort, to make an eventual flight to orbit Mars or its moons.

NASA staged a successful uncrewed test flight of the Orion capsule using a Delta 4 rocket in December 2014. Known as Exploration Flight Test 1, or EFT-1, the heavily instrumented Orion capsule was boosted into an orbit with a high point of about 3,600 miles above the Earth. From there, the spacecraft plunged back to Earth, hitting the atmosphere at some 20,000 mph to test its heat shield and other safety systems.