NASA blames moon rocket engine shutdown on hydraulic system software

Software in place to monitor hydraulic systems during a test firing of NASA's Space Launch System moon rocket was to blame for an early engine shutdown Saturday, not an actual problem with the booster's shuttle-heritage engines or its complex propulsion system, NASA said Tuesday.

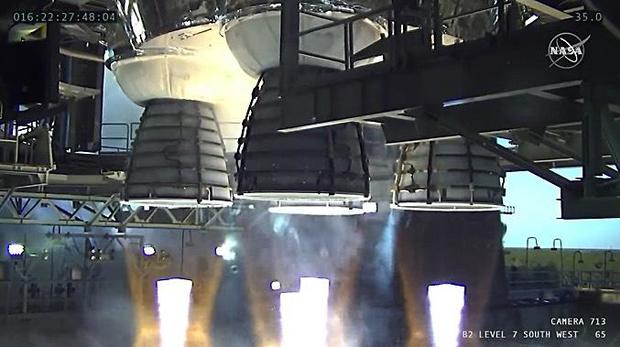

All four of the Aerojet Rocketdyne RS-25 engines operated normally throughout the test and while an instrumentation glitch with engine No. 4 was called out near the end of the run, it was unrelated to the shutdown. NASA said the huge rocket was not damaged and otherwise performed normally.

Engineers are still assessing the test results to determine if another hot-fire test is needed at the Stennis Space Center in Mississippi where the rocket remains in place atop a massive test stand. It may even be possible to forego another test and press ahead with launch before the end of 2021 as originally planned.

But engineers must complete a detailed review of the test data before any such decisions can be made. One factor in the discussion: the rocket is certified for nine fuelings with super-cold liquid oxygen and hydrogen propellants and two complete cycles have already been carried out, one for a "wet" dress rehearsal and one for the actual hot fire test.

Either way, said Kathy Lueders, chief of NASA space flight operations, "we are still shooting for a launch this year."

But, she added, "we're not going to make the decision based on whether we can get a launch this year. We're going to make the decision based on what data do we need to ensure that when we get to our launch this year, we know we can execute it

Wayne Hale, former space shuttle program manager and veteran ascent flight director, said in a tweet "my advice would be to retest and get complete data." While a retest at Stennis would take additional time, "schedule is secondary."

The Space Launch System rocket will be the most powerful ever built, generating a staggering 8.8 million pounds of thrust at liftoff -- 7.2 million pounds from two strap-on solid-fuel boosters and 1.6 million pounds from the four RS-25 engines at the base of the core stage.

NASA managers had planned to ship the Boeing-managed core stage to the Kennedy Space Center in February for a planned maiden flight before the end of the year to send an unpiloted Orion crew capsule on a long test flight beyond the moon and back.

The "green run" test firing was intended to last a full eight minutes, mirroring an actual climb to space. The engine start sequence went normally and all four RS-25s fired at full power for the first minute of the test run as planned.

An engine steering test was planned about one minute into the firing, using core stage auxiliary power units, or CAPUs, to hydraulically push and pull the engine nozzles to different positions as required.

But NASA said in a blog post that software limits put in place for the ground firing were exceeded and the rocket's computer system dutifully ordered a shutdown. The test firing lasted 67.2 seconds.

"During gimballing, the hydraulic system associated with the core stage's power unit for engine 2, also known as engine E2056, exceeded the pre-set test limits that had been established," NASA said. "As they were programmed to do, the flight computers automatically ended the test.

"The specific logic that stopped the test is unique to the ground test when the core stage is mounted in the B-2 test stand at Stennis. If this scenario occurred during a flight, the rocket would have continued to fly using the remaining CAPUs to power the thrust vector control systems for the engines."

The blog post said the rocket successfully transferred power to a redundant hydraulic system before the shutdown, adding that the engine gimbal test "was an intentionally stressing case for the system that was intended to exercise the capabilities of the system."

"The data is being assessed as part of the process of finalizing the pre-set test limits prior to the next usage of the core stage," the post said.

Observers initially heard a call on the control room audio channel referring to an "MCF," or major component failure, on engine No. 4 just before the shutdown. That led observers so suspect engine No. 4 caused the abort.

But NASA says the MCF call was the result of an instrumentation glitch unrelated to the shutdown and that the control system still had "sufficient redundancy to ensure safe engine operation during the test." Engineers expect to resolve the issue before the next use of the stage.

During a post-test news conference Saturday, John Honeycutt, NASA's SLS program manager, said an unusual "flash" was observed at or near insulation blankets protecting the interface between the four engine nozzles and the base of the rocket. NASA says some charring is evident, "but was anticipated due to their proximity to engine and CAPU exhaust."

"Data analysis is continuing to help the team determine if a second hot fire test is required," NASA said. "The team can make slight adjustments to the thrust vector control parameters and prevent an automatic shut down if they decide to conduct another test with the core stage mounted in the B-2 stand."