NASA awards nearly $1 billion in Artremis program moon lander contracts to SpaceX, Blue Origin and Dynetics

SpaceX and teams led by Dynetics and Blue Origin won NASA contracts Thursday totaling nearly $1 billion to develop lunar landers that could carry astronauts back to the moon as early as 2024 and support sustained, long-term operations by 2028 under the space agency's Artemis program.

"With these contract awards, America is moving forward with the final step needed to land astronauts on the moon by 2024, including the incredible moment when we will see the first woman set foot on the lunar surface," NASA Administrator Jim Bridenstine said in a statement.

"This is the first time since the Apollo era that NASA has direct funding for a human landing system, and now we have companies on contract to do the work for the Artemis program."

After two unpiloted test flights of Boeing's gargantuan Space Launch System (SLS) heavy-lift booster in 2021 and the 2022-23 timeframe, NASA plans to launch the first Artemis crew to the moon aboard a Lockheed Martin Orion capsule atop an SLS booster by the end of 2024.

Once in orbit around the moon, the astronauts will rendezvous with a lander, move aboard, undock and descend to the surface. They will land near the moon's south polar region where ice — a potential future source of propellants, oxygen and water — may be present in permanently shadowed craters.

The landing craft then will blast off, rendezvous with the Orion capsule in lunar orbit and head back to Earth.

Pulling that off by the end of 2024 is considered an extraordinarily difficult challenge given budget uncertainties and the sheer amount of new development required. Of more immediate concern, work slowdowns and stoppages across NASA in the wake of the coronavirus pandemic likely will force downstream delays.

But Bridenstine said congressional support remains strong and that he is committed to the Trump administration's fast-track schedule.

"We need to get to the moon soon," he told reporters during an afternoon teleconference. "The reason we go fast is because it enables the program to be successful. We've tried to go to the moon before, it takes too long, it costs too much money and it gets canceled. Going fast reduces the political risk."

But speed is just one part of the equation, he said. The other objective is long-term sustainability.

"We need to be able to go and be able to go again and again and again," he said. "The challenge with Apollo is that it ended. We want to make sure that this program, the Artemis program, goes on for generations to come."

A key to sustainability, Bridenstine said, is a small space station called Gateway that NASA plans to build in a high lunar orbit to serve as a staging base for landing at different sites around the moon. But the initial 2024 landing does not require Gateway, which may or may not be finished by then.

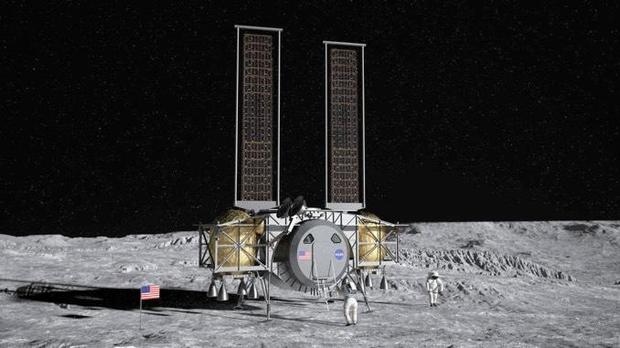

Blue Origin, a company owned by Amazon founder Jeff Bezos, was reportedly awarded $579 million to develop a lander with partners Lockheed Martin, Northrop Grumman and Draper Labs. Made up of three stages, the Blue Origin lander, capable of docking with the Gateway station, would be launched on the company's New Glenn rocket or a United Launch Alliance Vulcan booster.

Dynetics, partnering with Sierra Nevada, won a reported $253 million contract and would launch a two-stage, re-fuelable lander atop a Vulcan. It, too, would be capable of using the Gateway station. SpaceX was awarded about $135 million for a proposal built around the company's "lunar-optimized" Starship rocket. Much larger than its competitors, the Starship would not need to dock with Gateway to pick up supplies or other equipment.

The base period of the contracts, totaling $967 million, runs 10 months through next February. During that period, NASA will evaluate the proposals in detail and determine what sort of tests will be needed to certify them for human spaceflight. After that, NASA plans to award follow-on contracts to at least two teams.

NASA's source selection statement, listing the strengths and weaknesses of each company's proposal, shows Dynetics with "very good" management and technical ratings, the highest of all three. Concerns included a complex power and propulsion system that "relies upon technologies that are at relatively low maturity levels or that have yet to be developed ... but would need to be developed at a speed that does not align with historical experience."

Blue Origin received a "very good" management rating and an "acceptable" technical rating. Concerns listed were the complexity of the descent stage's propulsion system, Blue's lack of flight experience and "multiple relatively low technology readiness level systems that will be challenging to manufacture, integrate, and test."

"Technically, the design appears to be sound, but this design can only come to fruition as a result of a very significant amount of development work that must proceed precisely according to Blue Origin's plan, including occurring on what appears to be an aggressive timeline," according to the source selection statement.

SpaceX came in third with a rating of "acceptable" in both management and technical arenas. While the lunar variant of the Starship system offers numerous advantages, including two airlocks and the ability to carry 100 tons to the moon's surface, it's propulsion system is complex, according to the source selection statement, and the system "requires numerous, highly complex launch, rendezvous and fueling operations which all must succeed in quick succession in order to successfully execute on its approach."

"These development and operational risks, in the aggregate, threaten the schedule viability of a successful 2024 demonstration mission," the statement said.

But all three proposals were praised for innovative strategies that will "undoubtedly result in a multitude of scientific, technical and exploration advancements, including significant advancements that are as-yet unforeseen. NASA, its international partners and the commercial spaceflight industry stand to realize considerable benefits if these three offerors are awarded HLS (human landing system) contracts."

Building a new lunar lander from scratch in less than five years is considered the most challenging element in NASA's new new moon program, and not just from a technical perspective. The space agency will require significant new funding to make the Trump administration's 2024 landing target a reality.

The administration is requesting $25.2 billion for NASA in fiscal 2021, a 12% increase that includes $3.3 billion to kickstart development of a human-rated lander for the Artemis moon program. Nearly half of the budget request, $12.3 billion, is devoted to new and ongoing projects focused on the return to the moon and eventual flights to Mars.

NASA documents indicate it will cost about $35 billion to fund the Artemis moon program through the first landing of a man and woman on the lunar surface in 2024. To make that happen, the budget request says NASA will need $25.2 billion in fiscal 2021, $27.2 billion in 2022, $28.6 billion in 2023, $28.1 billion in 2024 and $26.3 billion in 2025.

Whether a generally supportive Congress will go along with that level of spending in the wake of the coronavirus financial setback and ongoing bipartisan conflict remains to be seen.