Mysterious case of Caribbean sea urchin die-off has been solved by scientists

There seemed to be a deadly plague lurking under the crystal blue waters of the Caribbean last year, killing sea urchins at a rate that hadn't been seen in decades. For months, no one knew what was causing it.

Now, scientists say they have identified the mysterious killer.

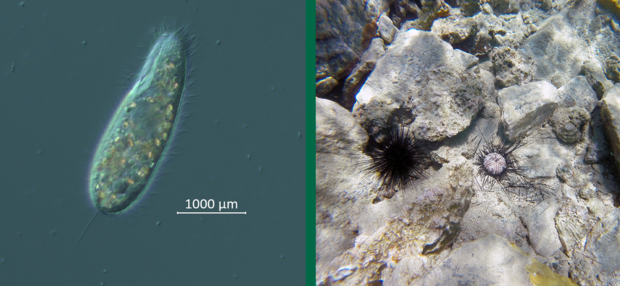

The giant issue was caused by none other than an organism so small, it's made up of only a single cell – a tiny parasite known as a ciliate.

A team of researchers uncovered the mystery, which saw long-spined sea urchins losing their spines in just a matter of days and dying in "droves," a press release from the University of South Florida said. Dive shops first started reporting the situation in February, but it's believed the "urchin graveyard," which covered thousands of miles between the U.S. Virgin Islands and the Caribbean to Florida's east coast, began a month earlier.

"This project in particular is a bit like a mystery novel, essentially whodunit? Who's killing off the urchins?" said Ian Hewson, Cornell microbiology professor and study co-author.

Scientists were immediately concerned about the event, as sea urchins – vital marine creatures that eat up the algae that would otherwise decimate coral reefs – were still recovering from another mass die-off in the area that had happened 40 years earlier. That event had killed off 98% of the long-spined sea urchin population in the region, scientists said. The cause for the early '80s die-off has yet to be determined.

"When urchins are removed from the ecosystem, essentially corals are not able to persist because they become overgrown by algae," Hewson said in the Cornell press release, an issue that is only increasingly important to address as global warming is expected to increase coral bleaching events so much so that the U.N. says it will be "catastrophic" for reef systems.

Mya Breitbart, the lead author of the study that was published in Science Advances on Wednesday, said her team is "beyond thrilled" but also "stunned" to have figured out what happened so quickly. What usually would take decades to determine, her team figured out in just four months.

"At the time we didn't know if this die-off was caused by pollution, stress, something else – we just didn't know," Hewson said in a USF release.

To solve the mystery, they looked at urchins from 23 different sites throughout the Caribbean. And there was a clear commonality between those that had been impacted by the event – ciliates. Ciliates are tiny organisms covered in cilia, which look like little hairs, that help them move around and eat.

"They are found almost anywhere there is water," a press release from the University of South Florida, where Breitbart works, says. "Most are not disease-causing agents, but this one is. It's a specific kind called scuticociliate."

The breed of ciliate has been linked to mass killings of other marine species, scientists said, but this is the first time it's been linked to the rampant decline of sea urchins.

Researchers were excited to figure out what the cause was, but even though they figured out who the culprit is of the mystery, they have yet to figure out how or why it started in the first place.

One theory is that the ciliate saw an "explosive growth," researchers said in their study. But more research is needed to determine whether that was a leading cause.

The finding could also help answer other questions happening underneath the waters nearby. Microbiologist Christina Kellogg said that there is some overlap between where the urchins were dying and where stony coral tissue loss disease was wreaking havoc on coral populations.

"Almost never are we able in a wildlife setting, at least in marine habitats, to prove that a microorganism is actually responsible for disease," Hewson said. "...Knowing the pathogen's identity may also help mitigate risk to untouched Diadema through such things as boat traffic, dive gear, or other ways it may be moved around."