A year after the military's violent takeover in Myanmar, a quiet battle to reclaim democracy simmers on

Bangkok — The lush Thai countryside just across the river from Myanmar shelters refugees from a fight they didn't pick. Some days, Myanmar military offensives are so close to the border that stray bullets ricochet over to the Thai side.

CBS News Asia correspondent Elizabeth Palmer says that's where tens of thousands of people — from Buddhist monks to political activists and everything in between — have taken refuge from the army, which seized power in Myanmar exactly one year ago on Tuesday.

The generals ousted the democratically elected civilian government, arrested its leaders and sent the army into the streets to take control on February 1, 2021. If they didn't anticipate any resistance, they were wrong. The protests that followed were huge and furious.

Thousands of Myanmar's people came out to denounce the ruling junta, ready to defend the fragile democracy that had only just begun to take root in their country.

But it was a rout: The army opened fire on the protesters, and hundreds were killed.

Kyaw Zay Y was there.

"At the time they were shooting at anyone," he told Palmer.

Zay Y wasn't shot, but he was among thousands of people arrested during the persistent street protests. He said security forces whipped him with an electrical cable before they released him, 10 days later.

As soon as he could, he fled.

Zay Y is now settled into a new home — a safe house across the river in the Thai border town of Mae Sot — with his family, including his brother-in-law, Myat Thu. Until a few months ago, he was a captain in Myanmar's army. In the fall, he decided to desert.

"I couldn't serve anymore," he told Palmer, because part of his job had become hurting civilians.

The United Nations human rights office said on Tuesday that at least 1,500 people have been killed in the protests against the coup over the last year. The junta's security forces have unlawfully detained almost 12,000 people in that period, more than 8,700 of whom remain in custody, according to U.N. human rights spokesperson Ravina Shamdasani.

Since the coup, some democracy activists have turned to violence. There have been hundreds of bomb attacks against the junta and its security forces. In the northern jungle, young people are volunteering for military training with Myanmar's armed ethnic groups.

On the Thai side of the river, former army captain Thu is pitching in — teaching military tactics online.

Also sheltering in Mae Sot are politicians, including former lawyer and activist Kyaw Ni. He's been designated Deputy Minister of Labor in the exiled National Unity Government of Myanmar, which is pressing the international community to recognize its legitimacy.

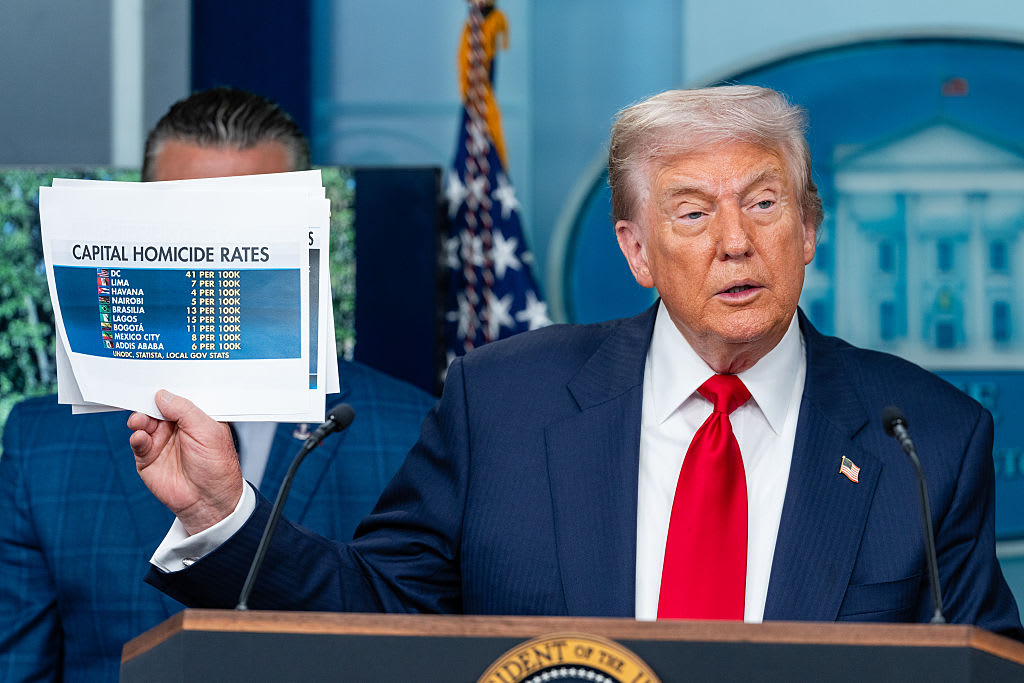

Crucially, the exiled government wants access to some of the roughly $1 billion in Myanmar government funds that has been frozen by the Biden administration.

"There are a lot of things we need the money for," Ni told Palmer. "A lot of our members are struggling in exile, and we need to support the civil disobedience movement inside Myanmar, and to help the people who are stuck in jail."

Aung San Suu Kyi, Myanmar's elected leader, was arrested by the generals and is now on trial on numerous charges that are widely views as spurious. It's very possible that she will spend the rest of her life in prison.

But the wider struggle is not dead.

One year on, Myanmar's democracy is definitely down. But millions of brave citizens are trying to make sure it's not out.