Music Biz's File-Sharing Dilemma

The music industry will have to make some very tough choices within the next week about file sharer Jammie Thomas-Rasset.

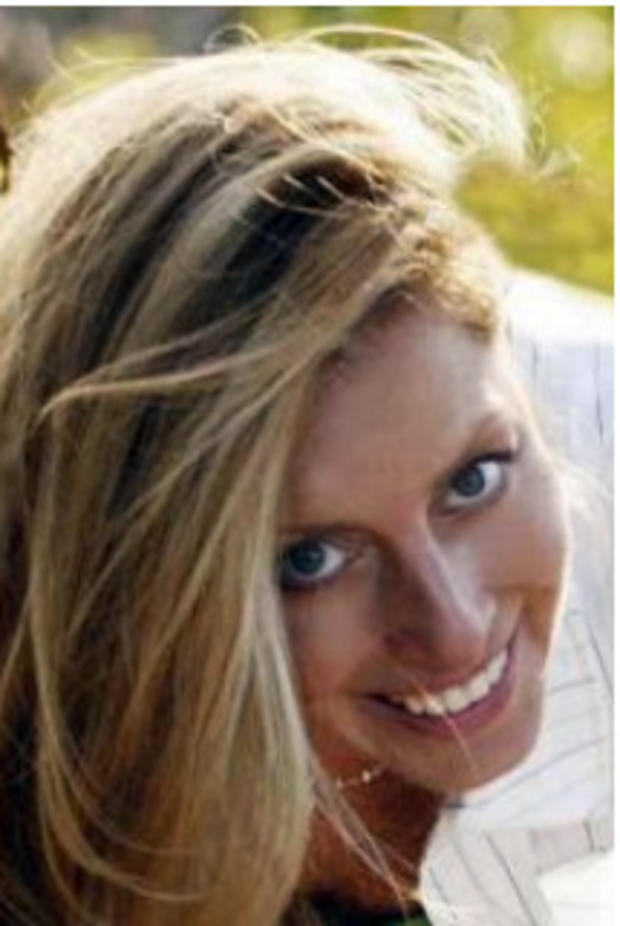

The Recording Industry Association of America wants to put the Thomas-Rasset affair behind it. The Brainerd, Minn., mother--who refused to settle with the RIAA for $5,000 over copyright infringement allegations, instead fighting it out in court--has been found liable of willful copyright infringement by two different juries and was ordered to pay damages of

On Friday, Michael Davis, chief judge for the U.S. District Court for the District of Minnesota, made what some legal experts say is

Davis has given the music industry seven days to decide whether to challenge his decision and schedule a trial on the damages. To figure out how to proceed, RIAA leaders and lawyers huddled on Monday, according to my music industry sources. An RIAA spokesman declined to comment.

Plenty of people within the RIAA, the trade group representing the four major recording companies, don't want to pursue the matter any further, the sources said. Some in the music industry believe that when it comes to deterrent value, Thomas-Rasset has served her purpose. They know that the strategy of filing lawsuits against those accused of illegal file sharing hurt the industry's image. That's one reason the group

Sometime this week, the RIAA could notify the judge that the group will not oppose his ruling. Some in the trade group's ranks hope that would put an end to the Thomas-Rasset case.

But hold everything: Thomas-Rasset's attorneys have challenged the constitutionality of even the minimum amount of statutory damages. Kiwi Camara, one of her attorneys, wrote at Copyrights and Campaigns, the blog operated by entertainment lawyer Ben Sheffner, that Thomas-Rasset plans to challenge even $1 in damages.

"This means that the RIAA cannot avoid the constitutional issue, even if (it accepts the latest ruling on the reduced damages)," Camara wrote.

Davis made some decisions in both trials that are unfavorable to copyright owners. Denise Howell, a Silicon Valley-based attorney, said Davis' district court rulings aren't binding in any other court but could be powerful precedents.

"There's some interesting language in (Davis' decision)," Howell said. "The constitutional nature of statutory damages comes up over and over again. If you're in any kind of copyright case, and you've gotten a very high damage award entered against you, you're going to want to bring this up and use Judge Davis' reasoning. I know a few folks in other copyright cases that have nothing to do with P2P file sharing but think this is quite an interesting development."

Davis' ruling reduced a jury award that was well within the dollar range set by Congress. The jury believed that Thomas-Rasset should pay $80,000 for each of the 24 songs she was accused of illegally sharing. That may have sounded "monstrous" to Davis, but that was less than the $150,000 per violation that Congress set as the maximum award.

The obvious question here for copyright owners is, what good are statutory damages, if any judge can come in and set his or her own range? Copyright attorney Sheffner says he sees plenty of room for the record labels to appeal.

"As far as I am aware, Judge Davis' decision is without precedent," Sheffner wrote on his blog, also noting that Davis did not cite precedents for his decision. "It stands alone as the first and only decision ever to reduce an award of copyright statutory damages."

Howell agreed that Davis' decision likely broke new ground.

"I could certainly see a court being persuaded that this shouldn't be the judge's decision," Howell said. "If the jury had awarded something above the range, then I think the decision would be ironclad. But that's not what happened. The judge looked at this and said, 'You know what? Even within this range, this amount is out of whack for what the actual damages might have been.'"

In addition to Davis' decision on damages, his "making available" ruling spooked the music industry, according to my sources.

In Thomas-Rasset's first trial, Judge Davis told the jury that "the act of making copyrighted sound recordings available for electronic distribution on a peer-to-peer network without license from the copyright owners violates the copyright owners' exclusive right of distribution, regardless of whether actual distribution has been shown."

Davis later said he erred in giving the jury those instructions because "it absolved the plaintiffs of proving 'actual dissemination' of their works," and he tossed the jury's decision and allowed Thomas-Rasset a retrial because of it.

The RIAA hasn't forgotten about that. The group's lawyers asked Davis to issue the same jury instructions in the second trial, and according to Sheffner, that was done to "preserve the issue for appeal."

Because the legal issues are complicated, and the RIAA must weigh a variety of concerns, the trade group likely will ask Davis for an extension beyond the seven days. We'll keep you updated throughout the week.

By Greg Sandoval