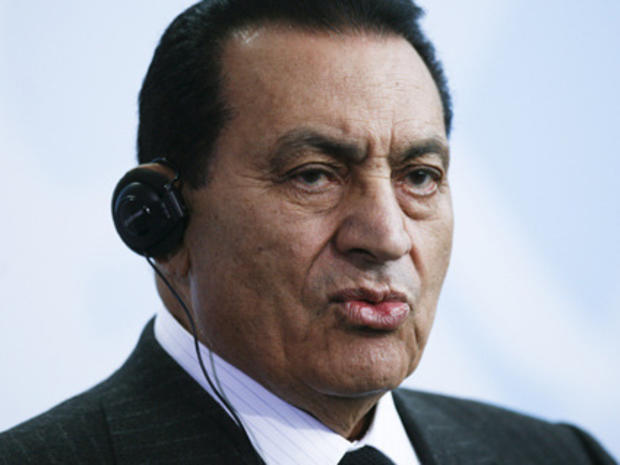

Mubarak Returns to Questions About Egypt's Future

Egyptian President Hosni Mubarak returns home later today after a "successful" surgery in Germany, but the long absence of the 81-year old longtime leader has fueled concerns over succession in the Arab world's most populous country.

Egyptians were set to see Mubarak on his feet for the first time in three weeks.

Last week, state television aired footage of the president for the first time since his gall bladder was removed on March 6, showing Mubarak — America's closest ally in the Middle East — sitting at a small table in a hospital room and talking to two doctors.

State media were careful to mention seven government officials in Cairo and two fellow Arab state leaders (including Syrian President Bashar Al-Assad) had a phone conversation with Mubarak and that he is back in business.

But despite the almost daily upbeat statements on the president's convalescence, there was no word when he would be discharged from the hospital, as anxiety over his health has amplified talk over the person actually running the country and who likely is to succeed the president.

Mubarak, president since 1981 — ever since the assassination of Anwar Sadat — has no vice president. He delegated authority to Prime Minister Ahmed Nazif temporarily and has said he will govern Egypt until his "last breath," which has raised speculation he may seek another presidential term next year, before passing the torch to his son, Gamal, the 46-year-old former investment banker.

Gamal has risen to a senior position in the ruling National Democratic Party and his allies dominate key economic portfolios in the cabinet. Father and son deny this speculation.

The founder of the Ghad Party, Ayman Nour, stood strongly against what he called Gamal's "inheritance of power," and called any move in this respect as an "insult" to political life in Egypt.

There are laws in the constitution intended to guide the transition of power.

But rules make it almost impossible for anyone not backed by Mubarak's ruling party to mount a real presidential challenge.

If the president dies in office or is declared incapacitated, powers will pass temporarily to the Speaker of Parliament, and an election must be held within 60 days. The first multi-candidate race was held in 2005, and Mubarak won easily.

By law, presidential candidates must secure the approval of 65 members of the People's Assembly, 25 members of the consultative Shura Council, and 10 members of municipal councils. As an alternative, candidates can be nominated if they have been leading members of parties that have been active for a minimum of five years before the election.

Under those terms, the decision-making on the next president is likely to happen in backroom dealings by those who wield power, not at the ballot box, according to analysts, who like others wanted to remain anonymous because of political sensitivities.

Cairo's cafes vibrate with theories around several scenarios. A rumor of Mubarak's demise a week ago, only a few hours before he appeared on TV, sent Egypt's stocks down, as the average per-capita income remains mired at about $1,800 a year.

"There are actually two scenarios," said Baha Ghorab, a journalist who works for international media. "Mubarak, the father, runs the election and wins and later transfers the power to his son for any reason. If Mubarak died, and this is the second scenario, I would say it would be almost impossible for Gamal to take over due to the old guards."

"Unlike all three presidents since the Egyptian monarchy was overthrown in 1952, Gamal has no military background. It will be tough for him to establish his authority," Ghorab, 27, says as he smoked an apple-flavored waterpipe shisha in a downtown cafe.

Several people have been discussed as successors, including the powerful head of intelligence, Omar Suleiman, sometimes called here Egypt's "shadow ruler."

Mohamed ElBaradei, one of Egypt's best-known figures abroad for having led the International Atomic Energy Agency until last year, is another possible candidate. After 30 years abroad, the 67-year-old returned to Egypt in February to a savior's welcome. He has stirred up debate by saying he might run, and has drawn tens of thousands of supporters on Facebook and other sites.

Still, many people, including Baher the journalist, doubt ElBaradei will have a chance to win in any elections.

"He ran an agency with a staff of about 2,000. Egypt's population exceeds 80 million. ElBaradei says he wants to amend the constitution, but what is next? We need to know more. Egyptians want to see reform, a raise in salaries, good food, good education," Ghorab said.

Some say the Muslim Brotherhood, whose members hold a fifth of the seats in Parliament (far more than any other opposition group), is the main challenger to the ruling National Democratic Party.

But the group is banned under a rule preventing religious parties, and its members are often detained in security sweeps, so a Brotherhood presidential candidate would have to run as an independent — an intimidating task under Egypt's election rules.

Egypt's Muslim Brotherhood chairman Mohamed Badie has extended warm wishes to Mubarak and a safe homecoming in comments published by the Brotherhood's English language website Ikhwanweb.

Kifaya, the protest movement, is weak and divided. It is true it gained some notoriety and influence before the 2005 elections but is now caught up in internal rows. The strikes that have become a fixture of Egyptian life focus on salary demands and are not banding together into a movement with political demands.

One thing is clear: Whether in the next few months or in the next year or two, the curtain is bound to fall on Mubarak's almost 30-year rule. Behind the scenes, there is already evidence of the start of a power struggle in Egypt.

By CBS News' George Baghdadi reporting from Cairo