Mountains on Pluto, chasms on Charon thrill scientists

Post-flyby images from NASA's New Horizons probe show Pluto is a surprisingly active world in the deep freeze of the outer solar system, with jagged 11,000-foot-high mountains of frozen water dusted with a veneer of nitrogen, methane and carbon monoxide ice amid smooth plains and jumbled terrain that defies easy explanation, scientists reported Wednesday.

A distinct paucity of impact craters implies processes at work now or in the geologically recent past that have resurfaced large areas of Pluto, smoothing out the pockmarks so familiar on other small bodies. What powers that resurfacing is not yet known, but scientists are hopeful New Horizons eventually will provide the answer.

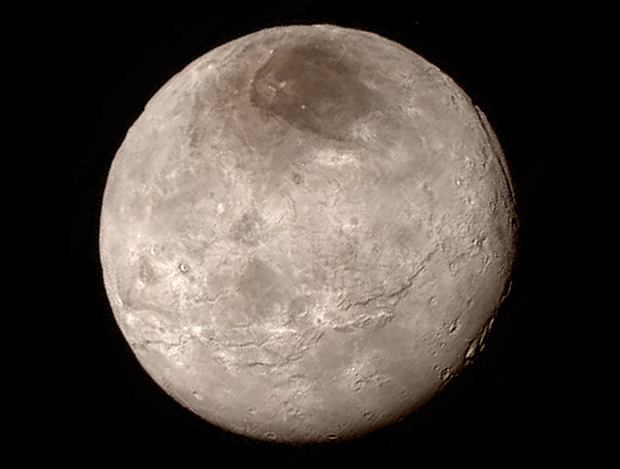

And what of Pluto's large, Texas-size moon Charon? A higher-resolution close-up photo unveiled Wednesday shows huge cliffs and troughs stretching hundreds of miles, deep chasms in the frozen crust and intriguing hints of structure in the moon's dark polar cap. Like on Pluto, craters are relatively few and far between.

NASA also showed the first photo of one of Pluto's four smaller satellites, Hydra, a pixelated image with a brightness corresponding to the presence of more water ice covering an irregular banana-shaped body.

New Horizons carried out its historic flyby Tuesday in radio silence, aiming its instruments at Pluto, Charon and the dwarf planet's other four satellites and storing the data on board until there was time to turn back toward Earth to transmit high-priority first-look data.

Alan Stern, the $720 million mission's principal investigator, said he was thrilled with the initial results.

"I had a pretty good day yesterday, how about you?" he joked before a cheering crowd of supporters on hand for the first post-flyby news conference. "We have big news," he continued. "From the first resolved image of Hydra, Pluto's outermost moon, to the discovery that Charon has been active. And there are mountains in the Kuiper Belt."

He was referring to the vast realm beyond Neptune where countless small bodies and larger worlds orbit, remnants of the formation of the solar system 4.5 billion years ago. Pluto, famously demoted from planethood shortly after New Horizons was launched in 2006, is the most famous member of the Kuiper Belt and the first such body to be visited by a spacecraft.

Charon is half the size of Pluto and the two make up what scientists call a binary planet. The two orbit a common center of mass well above Pluto's surface, circling each other in gravitational lockstep every 6.4 days.

Charon's first closeup from New Horizons revealed a baffling landscape with a surprising lack of impact craters.

"Originally, I thought Charon might be an ancient terrain covered in craters," said Cathy Olkin, New Horizons deputy project scientist. "And so, Charon just blew our socks off when we had the new image today. We've just been thrilled. All morning, the team has just been abuzz, 'look at this, look at that, oh my God that's amazing!'"

The dark reddish polar region, seen in earlier photographs taken farther out, shows more detail in the closeup view, with distinct regions that feature different shades. Olkin said the science team had nicknamed the area Mordor, the realm of the evil sorcerer Sauron in the "Lord of the Rings" trilogy.

Olkin pointed out a series of troughs and cliffs extending about 600 miles across the moon's surface and a huge chasm that cuts deep into the crust.

"That canyon is really quite deep, it's about four to six miles deep," Olkin said. "I find that fascinating. It's a small world, with deep canyons, troughs, cliffs, dark regions that are still slightly mysterious to us. There's another canyon ... and that one is about three miles deep. There is so much interesting science in this one image alone!"

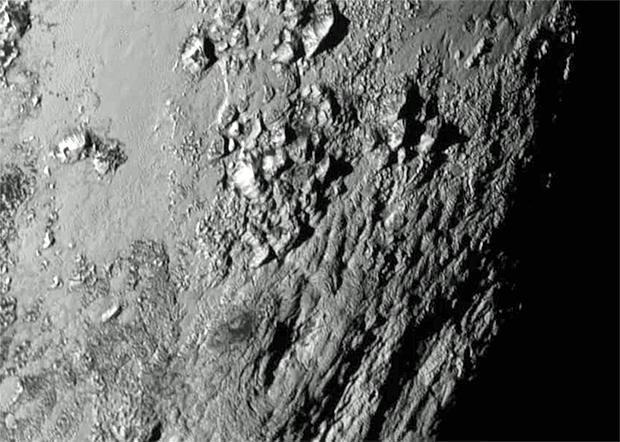

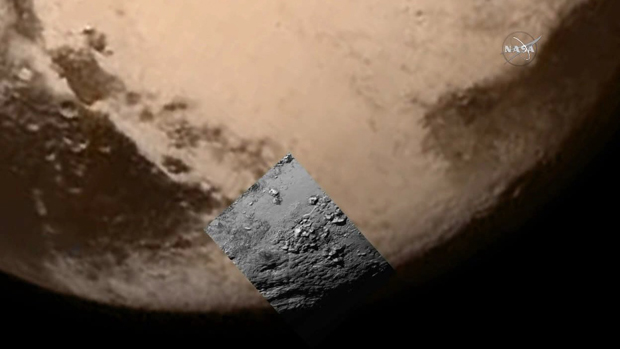

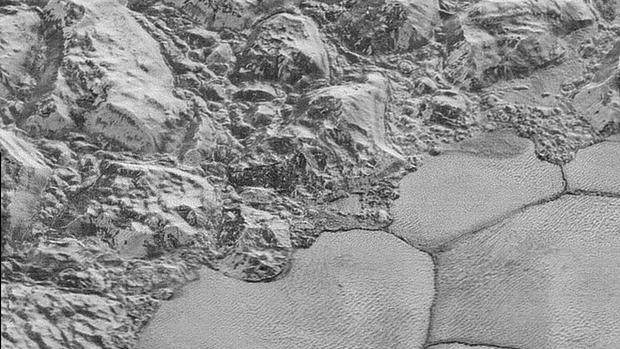

But the star of the show was the first close-up look at Pluto's surprisingly tortured surface, the first frame of what eventually will be a mosaic covering most of the dwarf-planet's day side. The area is near the bottom of a heart-shape region seen in earlier photographs.

"The most stunning thing about this image, the most striking geologically, is we have not yet found a single impact crater in this image," said co-investigator John Spencer. "This means this is a very young surface, because Pluto has been bombarded by other objects in the Kuiper Belt and craters happen.

"So, just eyeballing it, we think it has to be probably less than a hundred million years old, which is a small fraction of the four-and-a-half-billion year age of the solar system. It might be active right now. With no craters, you just can't put a lower limit on how active it might be."

Towering mountains can be seen, along with smooth plain-like areas and jumbled terrain Spencer could not immediately explain.

He described the mountains as "quite spectacular, these are up to 11,000 feet high, there may be higher ones elsewhere."

"Now we know the surface of Pluto is covered in a lot of nitrogen ice, methane ice, carbon monoxide ice," he said. "You can't make mountains out of that stuff. It's just too soft, it doesn't have the strength to make mountains. So we are seeing here the bedrock, or the bed-ice, of Pluto."

With a surface temperature of nearly 400 degrees below zero Fahrenheit, "water ice is strong enough ... to hold up big mountains, and that's what we think we are seeing here," Spencer said. "So the nitrogen and the methane are just a coating on top of this icy bedrock and we're seeing that here."

Pluto is the first ice dwarf ever studied that does not orbit a gas giant like Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus or Neptune. Bodies orbiting the gas giants experience gravity-driven tidal stresses, generating internal heat that can, in turn, drive geological activity.

Case in point: Neptune's moon Triton, believed to be a captured Kuiper Belt body, which feartures geyser-like plumes spotted by NASA's Voyager 2 probe during a 1989 flyby.

Charon is not nearly massive enough to generate tidal heating.

"That can't happen at Pluto, there's no giant body that can be deforming Pluto on an ongoing, regular basis to heat the interior," Spencer said. "So this is telling us you do not need tidal heating to power ongoing recent geological activity on icy worlds. That's a really important discovery that we made just this morning."

Said Stern: "We've settled the fact that these very small planets can be very active after a long time, and I think it's going to send a lot of geophysicists back to the drawing board to try to understand how exactly you do that."

He said cryo-volcanism or geysers like those seen on Triton may be pulling volatiles like nitrogen, methane and carbon monoxide up from below the surface. While no signs of any such activity has been spotted in the quick-look data, "this is very strong evidence that'll send us looking ... for evidence of exactly these phenomenon."

In the meantime, the science team has its hands full trying to understand what's going on in the initial photos of Pluto's surface.

"There's been erosion, there's been mountain building, there's been whatever produces lumpy terrain with grooves on it," Spencer marveled. "And it's baffling. It's baffling in a very interesting and wonderful way."