Heroism, terror heard in 911 calls about climber's death on Oregon mountain

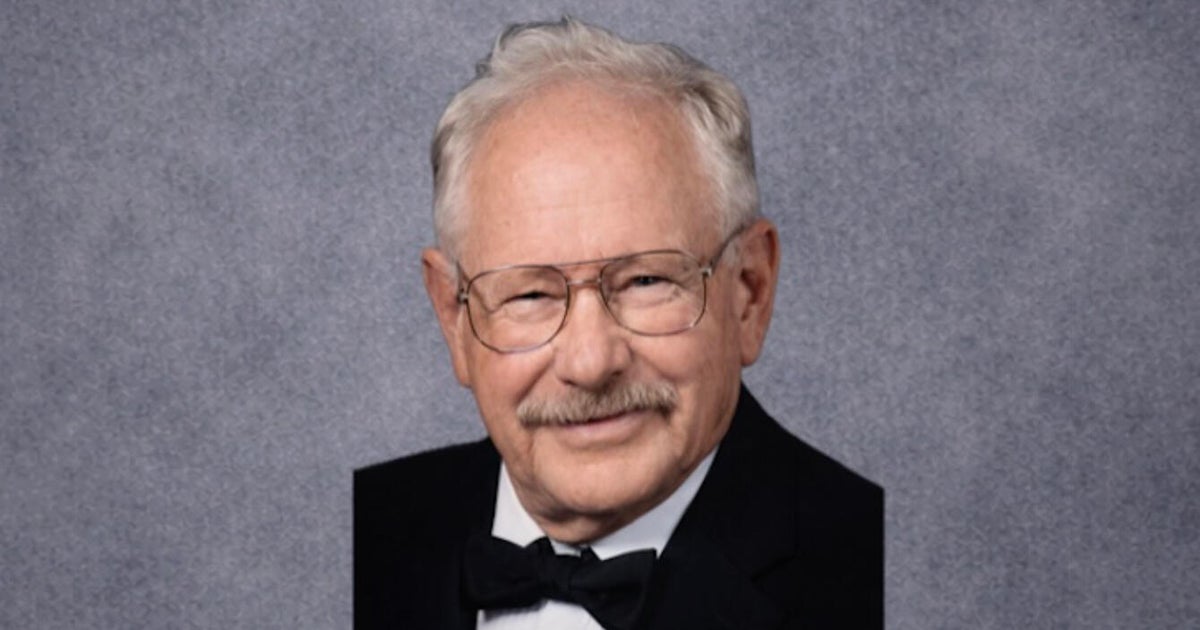

PORTLAND, Ore. -- The first thing that Braton Jurasevich noticed as he clambered down Mount Hood toward his fallen fellow mountain climber was the blood -- a lot of it. The critically injured climber, later identified as Miha Sumi, was sprawled with his feet above his head on an icy slope about 10,300 feet up the mountain.

Moments before, Sumi had slipped while descending from the summit and plummeted head over heels down a snowfield on Oregon's tallest peak -- his fall witnessed by nearly a half-dozen other climbers who called 911 as they watched helplessly.

Sumi would be pronounced dead at a Portland hospital later Tuesday after being airlifted off the slope. But when Jurasevich arrived, he was still alive.

"I'm the only one with eyes on the individual right now and I'm still 200 feet above the climber. He is not moving. I'm working my way down on a bad spot. I came across blood. There's a big blood trail," he tells the 911 dispatcher at the beginning of a call made public by the Clackamas County Sheriff's Office late Wednesday.

Sumi had come to rest in the shadow of a rocky outcropping known as Crater Rock, stuck in a chute that acted like a natural funnel for a barrage of rocks that slammed down the mountain as the sun warmed the ice and sent ice and rocks plummeting downhill.

As Jurasevich inched closer, those rocks careened past, making rumbling sounds in the background of the call. A terrified Jurasevich tells the operator he's not an experienced climber and doesn't know what he's doing, but will stay with Sumi until help arrives.

"Oh my God, a rock just went right by him. The sun's out and it's bad. The whole hill is falling apart," he says, breathing heavily into his mobile phone.

"We're still taking rocks and ice. ... Can you take a message for my mom for me? Tell her I love her," Jurasevich says a few moments later. "I'm in a bad spot."

The dramatic call is part of a release of three hours of 911 calls from the chaos on Mount Hood. While the 911 operator was on the line with Jurasevich, other climbers also called in to report seeing Sumi fall or to report that they were in trouble.

A woman who had been climbing with Sumi called 911 to report she and two others were stranded high up Mount Hood, pinned down by sheets of falling ice and tumbling rocks and unable to reach him.

"We just want to know what's going on with our friend," the woman, Kimberly Anderson, says to the dispatcher while crying.

Another shaken climber called moments after Sumi's fall to say he wanted to climb down to his friend but was in a perilous position.

"I'm not sure if I can get to him. It's far, it's really far," said the friend, Matt Zavortink. "I thought maybe I thought I saw him moving, but I can't tell. I'd expect severe injuries."

The unidentified female 911 operator stayed on the phone with Jurasevich for more than two hours as he tried to save Sumi, first by himself and then with the help of several other climbers who reached the scene.

The climbers first reported Sumi's pulse was 64 and he was breathing regularly, but they began rescue breaths and then CPR as his pulse faded and his breathing became erratic and then stopped. The callers continued CPR for 90 minutes until a rescue helicopter arrived, even though Sumi's pupils were fixed and dilated.

The call is punctuated by warning shouts about tumbling rocks. At one point, the climbers move their backpacks above Sumi's head to protect him.

"Hey Miha, if you can hear us, hang in there," Jurasevich can be heard saying. "You're looking good, you're doing good. We're going to get you a ride out of here."

Anderson, the female caller in Sumi's party, was evacuated from the mountain nearly seven hours later on a sled after she became unable to move for reasons that have not been explained by authorities.

The other climbers were either brought down by snow tractor or hiked out with rescuers.

It was unclear how Jurasevich and the other climbers who helped Sumi got off Mount Hood.

Jurasevich did not answer his phone Thursday and his voicemail was full.

About 10,000 people climb Mount Hood each year, making it one of the most popular snow-covered peaks in the U.S. Its proximity to Portland and its accessibility contribute to that popularity. But conditions on the peak, which has 11 active glaciers, can be dangerous.

More than 130 people have died on the 11,240-foot mountain, including seven school children and two teachers who froze to death in 1986 and several climbers whose bodies haven't been found.