Climbing Mount Everest: once lonely, now crowded, but always treacherous

When the British mountain climber George Mallory was asked, nearly a century ago, why he wanted to climb Mount Everest, he famously replied, "Because it's there."

Mallory died on his third attempt.

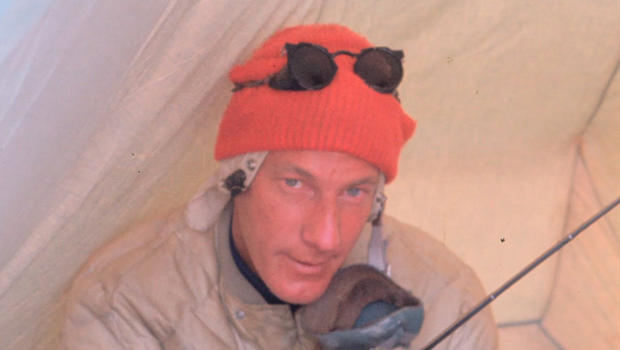

Jim Whittaker also tried - and made it. In 1963, Whittaker was the first American to reach the summit. He says he was lucky to survive.

"We're at 27,500 feet, we crawl out of the tent and the winds are 50 miles an hour and it's 35 below zero," he recalled.

CBS News interviewed Whittaker last year on the 50th anniversary of his historic climb.

Back then, climbing Everest was extremely treacherous and lonely. It's still treacherous, but far from lonely.

Conrad Anker, one of the world's most accomplished mountaineers, said climbing Everest was "very much a commercial business."

"When Jim Whittaker climbed Everest in 1963, he was the ninth person to the summit, and this year there's 300 plus permitted climbers and probably 400 climbing Sherpas in support of those climbers," he said.

Last year alone 658 climbers and guides reached the summit. It took 41 years -- from 1953 to 1994 -- for the first 658.

The percentage who reaches the summit is also climbing, from 24 percent in 2000 to 64 percent in 2013. That's due mainly to better gear, better guides and improved weather forecasting.

"If you're a good climber, you can make it to the summit within your safety parameters, but you're all equal when you're walking through that ballroom of death," he said.

The "ballroom of death" is what some climbers call those areas where avalanches are most likely and where they say the difference between life and death is not training or natural ability -- it's luck.

To help the Sherpas and their families in the wake of the recent avalanche, visit SherpaEdFund.org and JuniperFund.org.