Is it time to end this beloved tax break?

Every year, millions of Americans use the mortgage interest deduction as a way to save on their taxes. Less clear, however, is whether this perk actually spurs homeownership and benefits the middle-class.

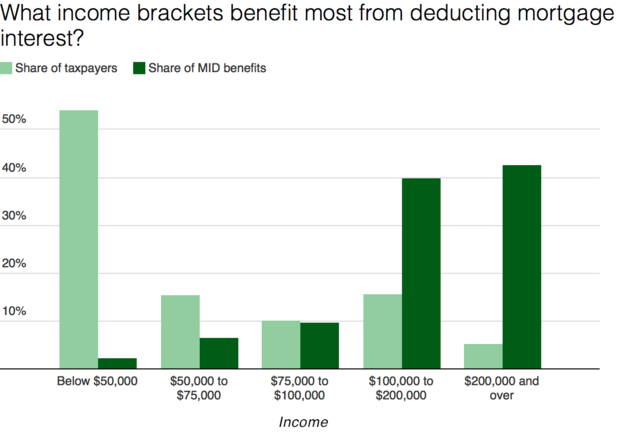

While it's well-known that this cherished tax deduction predominantly favors upper-income earners, especially those who live in expensive coastal states, experts are increasingly questioning the tax break's fairness in an economy where lower-income families are struggling with rising rent burdens. To put it in perspective, taxpayers subsidize well-heeled homeowners to the tune of $70 billion annually, yet spend less than $30 billion per year on the Section 8 rental voucher program for low-income families.

The mortgage interest deduction (MID) is often said to serve as an incentive for people to buy homes. Yet some research suggests otherwise. The tax break has "zero effect" on homeownership, according to a recent study from MIT economist Jonathan Gruber and two co-authors. The biggest barrier to purchasing a home is saving for a downpayment and affording the transaction costs, which aren't issues the MID addresses. At the same time, wealthier Americans who can afford to buy a home are given preferential tax treatment compared with renters.

"We rarely see tax expenditures as handouts. If it's a tax credit, you are working, you aren't on the dole, so you earn your tax benefit. The mortgage interest deduction is seen as a reward for playing by the rules," said Doug Ryan, director of affordable homeownership at Prosperity Now, a non-profit that advocates for economic opportunity for low-income families. "But if you are receiving Section 8 or are in public housing, you're seen as not holding your share of the bargain."

He added, "But it doesn't make sense to look at them differently, because they are both housing policies that cost the government billions a year."

Higher-income families in the U.S. tend get the better end of the deal, however. Households that earn more than $200,000 per year receive federal benefits of more than $6,000 annually, or four times the roughly $1,500 received by households earning less than $20,000, according to the Center for Budget and Policy Priorities, based on 2015 data.

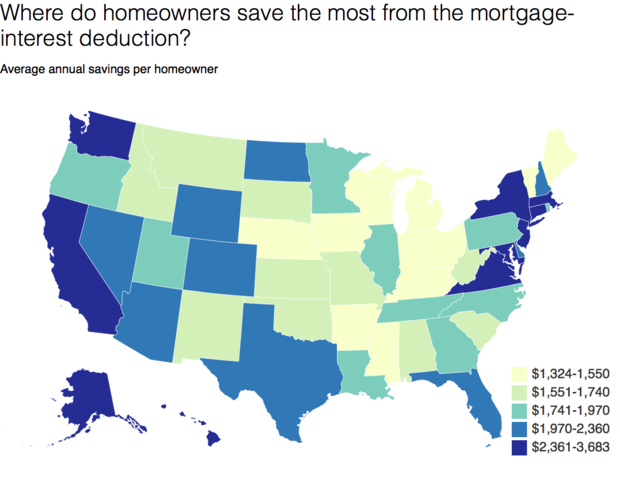

Households in mid-Atlantic, New England and Western states such as California benefit the most, according to a report published earlier this year from the Congressional Budget Office. On a per-capita basis, residents of Washington, D.C. receive the biggest boost, with a per person tax expenditure estimate of $436. The states receiving fewer benefits are primarily in the South and Midwest.

The post-recession economy has lifted the fortunes of the top 1 percent of American earners, while middle-class and low-income Americans have struggled with stagnant income. While pay hasn't yet caught up to its pre-recession levels, housing costs have soared, especially in many big cities where jobs are plentiful. Affordable housing, though, is increasingly out of reach.

About four of 10 Americans rent their homes, a rate that represents a 50-year high, according to a report from Harvard University's Joint Center for Housing Studies. It's not only millennials who are swelling the ranks of renters -- Americans over the age of 55 represent the largest growth in renters.

About 11 million renter households are paying at least half their incomes toward housing, an issue that's particular acute for lower-income families living in expensive cities like San Francisco and New York, the report said. Builders aren't adding enough new housing stock to keep up with demand, and post-recession housing has tended to skew to higher-end properties.

Eliminating the mortgage interest deduction would help put renters on an even footing with homeowners from a tax code perspective, according to the nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office.

"It's important that our tax expenditures, like the mortgage interest deduction, are doing what we want them to do and making sure they are well targeted to folks at the bottom and the middle of the income distribution," said Ryan Nunn, policy director for The Hamilton Project, an economic research group. "We should think about whether we can promote homeownership in a way that it doesn't accrue to those with disproportionately high income."

President Donald Trump's tax reform proposal takes a step toward weakening the appeal of the mortgage interest deduction. Because his plan would double the standard deduction to $12,000 for individuals and $24,000 for a married couple, fewer homeowners would need to itemize deductions.

The flip side: The MID would be skewed even more to the rich, with real estate firm Zillow estimating that it would be worth taking for only the top 5 percent of homes, or those worth more than $801,000. Almost 60 percent of San Francisco homeowners would still take the deduction, while fewer than 1 percent of Pittsburgh homeowners would do so, the real estate services firm calculated.

Instead, policy experts say there are a number of other levers the federal government could pull to encourage homeownership and help middle- and low-income families.

"The mortgage interest deduction doesn't work as an equalizer," Ryan said. "We are at a point where we should be very much concerned about this generation and the next generation or two of adults. Will homeownership still be on the table for them? We know we have the tools to make this work."

Below are some of the proposals from policy experts to reform the mortgage interest deduction.

Eliminate it. Getting rid of the MID would make the tax code not only fairer, but also would provide an increase in federal revenue, which would improve the U.S. budget or free up money for other programs, some experts say. However, given its beloved status among Americans and support from groups like the National Association of Realtors, many feel this is an unlikely scenario.

Cap and reshape it. Others support tweaks to the deduction, such as limiting the amount that can be deducted. Currently, the MID can be claimed on interest paid on up to as much as $1 million in mortgage debt, and also can be used for second homes. Capping the benefit to homes worth no more than $500,000 is one idea, as well as excluding second homes from the tax break or limiting the amount of interest that can be deducted.

Replace it. Some policy experts suggest creating an entirely new plan that would more broadly encourage homeownership. One such idea from the American Enterprise Institute's Alan Viard, who wants to replace the MID with a 15 percent refundable tax credit that would be available to all homeowners, even those who claim the standard deduction. That would preserve an incentive for property ownership, while making it more equitable, he wrote in a 2013 paper.