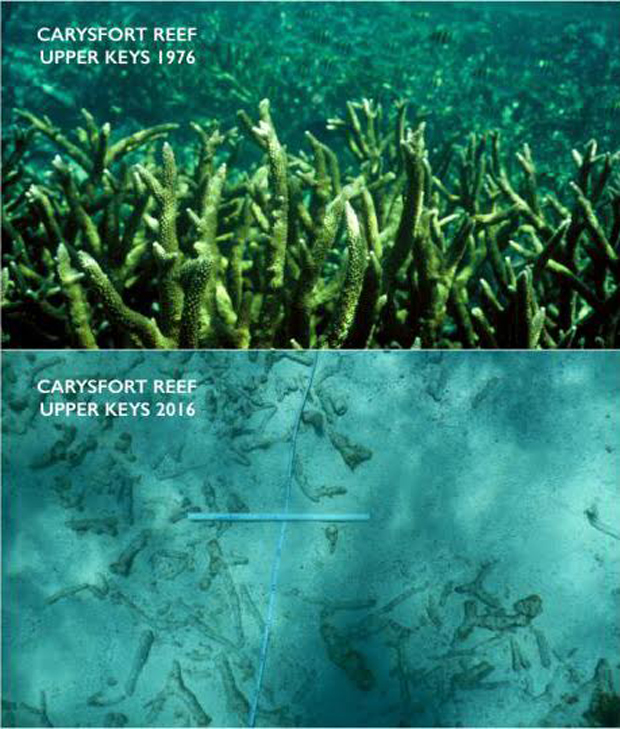

More acidic seawater eating away at Florida Keys reef

WASHINGTON -- Seawater, increasingly acidic due to global warming, is eating away a tiny part of the limestone framework for coral reef in the upper Florida Keys, according to a new study. It's something that scientists had expected, but not so soon.

This is one of the first times scientists have documented long-term effects of ocean acidification on the foundation of the reefs, said study author Chris Langdon, a biological oceanographer at the University of Miami.

"This is what I would call a leading indicator; it's telling us about something happening early on before it's a crisis," Langdon said. "By the time you observe the corals actually crumbling, disappearing, things have pretty much gone to hell by that point."

The northern part of the Florida Keys reef has lost about 14 pounds of limestone over the past six years, according to the study published in the journal Global Biogeochemical Cycles. The water eats away at the nooks and crannies of the limestone foundation, making them more porous and weaker, Langdon said.

So far the effect is subtle, not noticeable to the eye, and can only be detected by intricate chemical tests. But as ocean acidification increases, scientists expect more reefs to dissolve and become flatter, and that fish will leave, Langdon said. Also, increasing acidity eats away at the shells of the shellfish, making them easier prey for other fish and harder for humans to harvest.

Acidification occurs when oceans absorb more carbon dioxide from the air, altering seawater chemistry. Scientists expected limestone to dissolve, but not until the second half of this century. It's about 40 years early, Langdon said.

"This is another one of those cases where we're finding that we're underestimate the level of damage caused by excess carbon dioxide in the atmosphere," said National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration reef watch coordinator Mark Eakin, who wasn't part of the research.

Eakin and two other outside experts said the study made sense. But NOAA's Derek Manzello, a scientist in the ocean acidification program who studied the same area earlier, said it is difficult to blame the foundation loss just on ocean acidification, because long-term coral bleaching and death will also cause the limestone to dissolve.

There's a natural cycle of limestone production on reefs. Limestone generally grows faster in the summer as the water become less acidic and ocean life absorbs carbon from the ocean. But in the winter and fall, life dies off, carbon is released and the water becomes more acidic naturally, slowing or stopping limestone growth.

But "to actually see a negative was a big surprise," Langdon said. Extra, man-made carbon dioxide is being absorbed by the water and adding to its acidity. And it's worse in the northern parts of the Keys, because the colder the water, the more carbon dioxide dissolves into it, Langdon said.

Reefs provide $2.8 billion a year to the Florida economy, mostly from tourists who come to dive and fish but also from commercial fishing, Langdon said.