Monty Python's Terry Jones: An appreciation of a comic zealot

He was a joyful actor who played both the argumentative mother of the man who was not Jesus Christ, and an obscenely obese man who explodes after eating just a little too much. British writer, director and actor Terry Jones, a founding member of the comic troupe Monty Python, was more than happy to put on a woman's dress (or, as in the case of his Nude Organist, nothing at all) in the pursuit of the absolutely silliest comic ideas. His willingness to go to extremes knew no bounds.

Jones' specialty as a writer was a nonsensical premise presented as if it were totally ordinary, even mundane. The Spanish Inquisition (which nobody ever expects) suddenly pops up in people's houses and they don't bat an eye. And why wouldn't a café offer nothing on the menu except Spam, enjoyed by singing Vikings?

And the characters he played could be exquisitely silly, from a government cabinet official who delivers an address while strip-teasing, to a mousey little man whose every utterance, even contemplations of suicide, causes people to collapse in fits of laughter. He was also comfortable in the director's chair, having helmed the Pythons' last two films, "Life of Brian" and "The Meaning of Life," perhaps the only person who could wrangle the group's myriad comic sensibilities.

And while he was the last to want to let go of Python when the group ceased producing television shows and films, it turned out that Jones' solo pursuits put him leagues ahead of the others in terms of his breadth. He directed the non-Python films "Erik the Viking," "Mr. Toad's Wild Ride," and "Personal Services," and an episode of "The Young Indiana Jones Chronicles."

And it was not just about getting laughs: He published books of his research on history and literature, including an academic treatise on Chaucer. He presented TV documentaries about the Crusades and medieval history, silent films, cartography, and economics (this one told with puppets). And he wrote political and anti-war op-eds for newspapers. "He's got the widest spread of all of us," fellow Python John Cleese has said.

Jones died Tuesday at age 77, four years after he was diagnosed with frontotemporal dementia (FTD), a condition that robbed his loquacious, boisterous and inquisitive personality of speech. It was not unlike Beethoven losing his hearing, a defining part of his personality and gifts. It was a tragic turn of events for one whose entire life was the pursuit not just of laughs but of human engagement.

Eric Idle, another founding member of Python, told CBS News, "It hit me harder than I expected even though we were expecting it. There's no simple way to say how much I loved him. All those years. Funny and honorable. Since 1963. Too sad."

Terence Graham Parry Jones was born on February 1, 1942 in Colwyn Bay, Wales. Though his family later moved to Claygate in the English county of Surrey, his Welsh temperament never strayed far (as evidenced by his arguments with the very British Cleese over the minutest tangents of comedy). He attended Oxford, studying history, and it was there that he began writing and performing in comedy revues with future writing partner Michael Palin. After graduation, the two began contributing to David Frost's BBC comedy series, "The Frost Report," where they came into contact with Cambridge graduates John Cleese, Graham Chapman and Eric Idle.

During the 1960s Palin and Jones wrote for several comedians, including Marty Feldman, and were sometimes shocked at how their material would be changed, ruining the comedic effect. That fueled their desire to perform their own work. They wrote and starred in the parody "The Complete and Utter History of Britain," and (with Idle) "Do Not Adjust Your Set." But even then, Jones was dissatisfied with how directors often framed or edited their sketches, which prompted him to take courses in directing at the BBC.

In 1969 Jones, Palin, Idle and American Terry Gilliam (who contributed cartoons and animation to "Do Not Adjust Your Set") teamed with Cleese and Chapman to produce their own BBC series. Inspired by "Goon Show" creator Spike Milligan, whose '60s TV series "Q" had broken more than a few barriers in storytelling and presentation, Jones wanted to bring a stream-of-consciousness style to their show, so that explosions of humorous ideas wouldn't be constrained by situation comedy characters or a sketch show straitjacket of "set-up followed by punchline." It wouldn't be a musical/variety format with guest stars, either. It would be its own thing, and as TV viewers soon learned, "Monty Python's Flying Circus" wasn't like anything else.

The "Spam" sketch from "Monty Python's Flying Circus":

Perhaps Jones' greatest contribution to the TV show (apart from his willingness to dress up as rather unflattering, dowdy women) was his undying passion and enthusiasm for comedy. This would often lead to fights with Cleese — whose writing partnership with Chapman resulted in aggressive/absurd material that was quite different from Palin and Jones' silly/absurd material — about what was funny. It was his willingness to argue for the ridiculous, and to maintain a high quality in filming and editing, that drove the train that was Python, and it was his energy and enthusiasm, his eagerness to insert himself into the editing process, and his passion for fighting battles (and re-fighting them) about material, that kept the group together as long as they were.

Ever protective of their work, he was even responsible for having a line added to the Pythons' initial contract with the BBC that would, years later, result in the group owning their own shows — a rarity in TV.

After two seasons of "Monty Python's Flying Circus," Cleese was already angling to leave the show, fearing they were beginning to repeat themselves, but Jones argued for another year. By the time of the show's fourth series, in 1974, Cleese bowed out of performing, but kept with the group to appear in the film "Monty Python and the Holy Grail." And it was in the films that Jones' contributions shined the brightest.

Having worked under director Ian MacNaughton on their 1971 movie "And Now for Something Completely Different," a compilation of "Flying Circus" sketches aimed at the American market, Jones and Gilliam opted to co-direct "Holy Grail," with each bringing their own particular bent — Jones, a love of performing and of medieval history; Gilliam, a love of stark visuals and earthy textures — to a knockabout farce involving King Arthur and his Knights of the Round Table. The film was a hit and remains perhaps the most authentic-looking depiction of medieval life, even if what was being depicted was remarkably silly. In addition to directing, Jones played Sir Bedevere, Prince Herbert (who only wants to sing!), and an old woman who argues with King Arthur about collectivism and the monarchy.

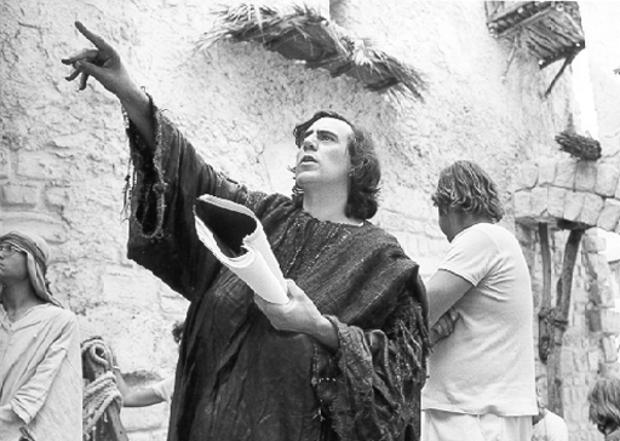

Having butted heads too often during the "Holy Grail" shoot, Jones and Gilliam decided it'd be best if Jones handled directing duties on their next film, "Life of Brian," himself. The Pythons' Bible-era story of a man mistaken for the Messiah would draw condemnation from evangelical groups who hadn't bothered to see the film, but it stands today as one of the greatest comedies ever made. Jones also starred as Mandy, the mother of Brian, who gets to admonish a crowd following her son, "He's not the Messiah; he's a very naughty boy!"

As the Pythons' collective output lessened, with each member pursuing their own solo projects, Jones seemed the most resistant to letting go of the group, as if he were not confident that he could have the same level of success on his own. He fought hardest for their last film together, "The Meaning of Life," which contained some of the group's most esoteric bits, and Jones' most memorable character, Mr. Creosote, a glutton who eats practically everything on the menu at a fancy restaurant, only to top off his meal with a "wafer-thin" mint, upon which he explodes. (It's safe to say it was the only film in history featuring projectile vomiting that won a top prize at the Cannes Film Festival.)

But after "Meaning of Life," which was released in 1983, Jones pursued projects that were extensions of his catholic interests in literature, history, science and film, including writing children's stories and a true-crime book, "Who Murdered Chaucer?" His fantasy book "Evil Machines" became the basis of an opera. And in 2008 he presented the BBC's annual April Fool's joke, as host of a nature film about flying penguins.

Financial hardships (the Pythons had lost a court case over royalties connected to the Broadway musical "Spamalot") led to their 2014 reunion. The five surviving members (Chapman had died in 1989) appeared in ten sold-out shows at London's O2 Arena, a performance beamed via satellite around the world. He performed the gang's immortal sketches with the same zeal, but memory issues began to become apparent. The following year, at an on-stage reunion in New York City at the Tribeca Film Festival, celebrating the 40th anniversary of "Holy Grail," Jones seemed disengaged and tongue-tied, an extremely unusual state for the voluble and effervescent man.

It was at that point in time — having just directed the film "Absolutely Anything" and the documentary "Boom Bust Boom" — that he was diagnosed with frontotemporal dementia, a condition that affects parts of the brain controlling language and social behavior. Jones grew increasingly inward, unable to speak, and even though he would attend business meetings with the Pythons, and participate in the Alzheimer Society's Memory Walks, he soon retreated from public life.

Palin spoke in 2018 of visiting his friend and longtime writing partner: "He'll smile every now and then, there'll be a little chuckle, but you're not quite sure what it's connected to, but it's still something to be treasured."

Jones leaves behind two children, Sally and Bill, from his 42-year marriage to Alison Telfer, and a daughter, Siri, born to Anna Soderstrom, a Swedish-born Oxford graduate who'd met Jones at a book signing. (The two married in 2012.)

In a statement, Palin said, "Terry was one of my closest, most valued friends. He was kind, generous, supportive and passionate about living life to the full. He was far more than one of the funniest writer performers of his generation; he was the complete Renaissance comedian — writer, director, presenter, historian, brilliant children's author, and the warmest, most wonderful company you could wish to have. I feel very fortunate to have shared so much of my life with him and my heart goes out to Anna, Alison and all his family."

Today Idle tweeted about memories of "So many laughs, moments of total hilarity onstage and off we have all shared with him."

Terry Gilliam tweeted "Terry was someone totally consumed with life ... a brilliant, constantly questioning, iconoclastic, righteously argumentative and angry but outrageously funny and generous and kind human being."

Cleese tweeted, "It feels strange that a man of so many talents and such endless enthusiasm, should have faded so gently away..."

CBS News senior producer David Morgan is author of "Monty Python Speaks."