Monster galaxy swallowed another, smaller galaxy

The galaxy Messier 87 has quite an appetite.

New observations by astronomers at Max Planck Institute for Extraterrestrial Physics and other institutes have revealed that the giant elliptical galaxy swallowed an entire medium-sized galaxy over the last billion years.

It was not an unexpected finding since scientists believe it is in the DNA of galaxies to gobble up one another. Still, it is incredibly difficult to confirm that a galaxy merged with another because the culprit usually leaves no trace of its misdeeds.

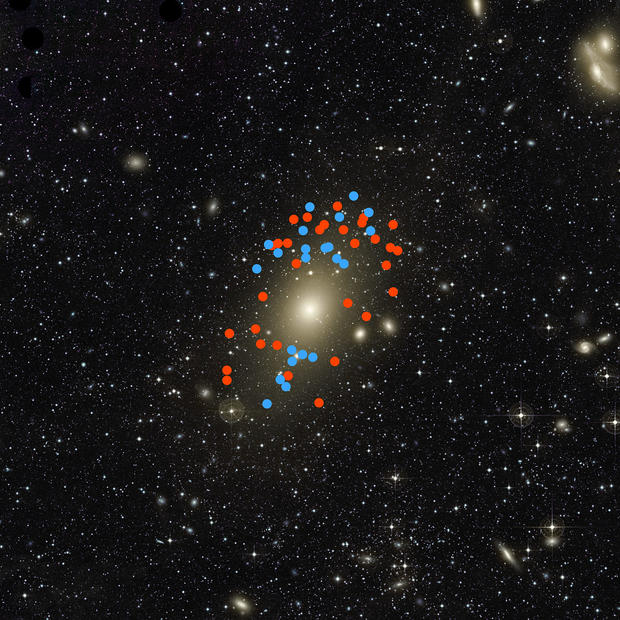

To confirm this indeed happened in the case of Messier 87, astronomers tracked the motions of 300 glowing, planetary nebulae. In addition, they found evidence of excess light coming from the remains of the smaller galaxy.

"This result shows directly that large, luminous structures in the universe are still growing in a substantial way - galaxies are not finished yet," Alessia Longobardi, a doctoral student at Max Planck and who led the study, said. "A large sector of Messier 87's outer halo now appears twice as bright as it would if the collision had not taken place."

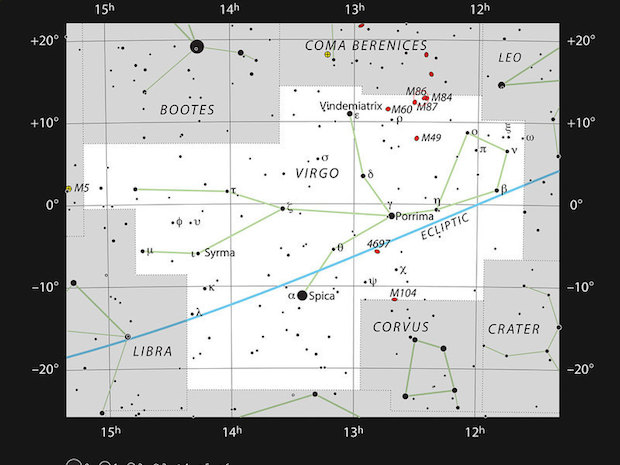

Messier 87, which lies at the centre of the Virgo Cluster of galaxies, is a vast ball of stars with a total mass of more than a million, million times that of the sun, at a distance of about 50 million light-years.

With it being impractical to study that many stars, the team chose to examine planetary nebulae, the glowing shells around aging stars. Because these objects shine very brightly in a specific hue of aquamarine green, they can be distinguished from the surrounding stars - showing their location and the velocity they are traveling.

But their brightness alone is not enough - after all the light emitted by a typical planetary nebula in the halo of the Messier 87 galaxy is equivalent to two 60-watt light bulbs on Venus as seen from Earth.

So the team also had to study their motions through careful observation of the light from the nebulae using the FLAMES spectrograph on the Very Large Telescope.

"We are witnessing a single recent accretion event where a medium-sized galaxy fell through the center of Messier 87, and as a consequence of the enormous gravitational tidal forces, its stars are now scattered over a region that is 100 times larger than the original galaxy," Ortwin Gerhard, head of the dynamics group at Max Planck Institute for Extraterrestrial Physics and co-author of the new study, said.

The team also looked very carefully at the light distribution in the outer parts of Messier 87 and found evidence of extra light coming from the stars in the galaxy that had been pulled in and disrupted. These observations also demonstrated that the disrupted galaxy has added younger, bluer stars to Messier 87. So, it was probably a star-forming spiral galaxy before its merger.

"It is very exciting to be able to identify stars that have been scattered around hundreds of thousands of light-years in the halo of this galaxy - but still to be able to see from their velocities that they belong to a common structure, " Magda Arnaboldi, another co-author from the European Southern Observatory said. "The green planetary nebulae are the needles in a haystack of red stars. But these rare needles hold the clues to what happened to the stars."