MLB's Orlando Hudson: "White man's game" image endures

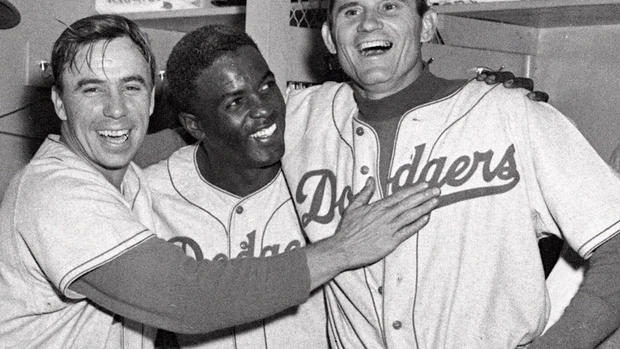

(CBS News) It's an ingrained narrative of America's pastime: When Jackie Robinson made his major league debut for the Brooklyn Dodgers on April 15, 1947, he paved the way for future generations of African-Americans to pursue their big league dreams.

But if Robinson were alive today, he may be dismayed by how the story has unfolded. As major league baseball commemorates the 65th anniversary of the Hall of Famer's milestone on Sunday, the league is seeing fewer and fewer African-Americans on the diamond. That downward trend and fading appreciation of Robinson's legacy doesn't sit well with San Diego Padres second baseman Orlando Hudson, one of a few dozen African Americans in the majors.

"I don't think the kids realize what Mr. Robinson had to go through, everything was against him, the skin color, (staying at) different hotels, (eating at) different restaurants, he overcame all that," Hudson told CBSNews.com. "Now so few blacks are playing baseball. How can this be? What happened?"

What happened is not easy to pinpoint but the numbers are hard to ignore. After Robinson's debut, major league baseball saw a steady rise in African-American players, peaking at 28 percent in the mid 70s. But the decades since have shown a dramatic decline. This season, only 8.8 percent of players on opening day major league rosters were African-American, according to an annual survey by the Institute for Diversity and Ethics in Sports.

Richard Lapchick, the institute's director, said he thinks major league baseball is committed to providing resources to reverse the trend. "But their programs will take time and we may have lost an entire generation before things can substantially change," he added.

Hudson, a two-time All-Star and four-time Gold Glove winner, said baseball has an image problem among black youth in America. While NBA and NFL stars like Derrick Rose, LeBron James and Michael Vick are ubiquitous on TV, baseball has very few high-profile African-American stars. Basketball and football also glamorize a "hip hop" culture that resonates with young African Americans, he said.

"They feel like baseball is a white man's game," Hudson said. "You go to a baseball game, they're not playing hip hop. They're playing Paul McCartney."

Baseball's relative lack of appeal is shaped by more than a soundtrack. Hudson, who's in his 11th MLB season, said that some aspiring African American athletes are also lured by the potentially quick path to the NFL and NBA. By contrast, even the top baseball prospects usually have to labor in the minors two or three years before making the big leagues.

But the underlying dynamics behind the dwindling numbers of homegrown black players in the major leagues have little to do with kids' quest for instant stardom or riches. Rich Berlin, the executive director of the Harlem chapter of Reviving Baseball in Inner Cities (RBI), said the lack of African-Americans playing baseball can be traced largely to geography and economics.

"Baseball requires space -- and in urban settings where many African-Americans live, that space just doesn't exist," Berlin said. "Also, MLB has obviously shifted their player development focus from American cities to Latin American countries as hubs for the development of athletes, where young people have space to play and develop at a much younger age. Not to mention that it costs less to do that in Latin America than in New York City or Los Angeles."

Indeed, the stats prove Berlin's observation. While major league baseball has seen a sharp drop in homegrown black talent over the past 20 years, it has seen a corresponding spike in Latino players. Last year, 38 percent of big league players hailed from Latin America.

Organizations like RBI, an initiative launched by MLB in 1989, have been successful in using baseball as a tool to engage inner-city kids. But Berlin is quick to point out that the program's ultimate goal is to foster teamwork among youths of all races and "develop happy, healthy and productive citizens" - not to produce the next major league superstar. Still, a handful of RBI alum have gone on to MLB stardom, including the Red Sox' Carl Crawford.

So it's perhaps no surprise that Hudson enlisted Crawford to help steer more African-American kids toward baseball. Each year, to honor Jackie Robinson, Hudson launches the Around the Mound Tour, which makes stops in major league cities from coast to coast. In addition to Crawford, Hudson has recruited other African-American stars like CC Sabathia, Torii Hunter, Juan Pierre and Ken Griffey, Jr. to help make the same pitch: encourage kids to play baseball and teach them to succeed on and off the field.

Hudson, an avid little leaguer growing up in Darlington, S.C., admits the first part of the message can be a tough sell. After all, for many young African Americans, baseball is neither accessible nor affordable when you can play basketball "for free at a rec center" down the street. But like the man who first trotted out on to Ebbets Field in 1947, Hudson says it only takes one person to make an impact.

"You're not gonna change everybody's minds, but if you can change one or two minds, at least you got something," he said. "We try to tell them: 'This is what Jackie Robinson stood for.'"