Making ideas into reality at MIT's 'Future Factory'

Back in the 1980's a laboratory of misfits foresaw our future. Touch screens, automated driving instructions, wearable technology and electronic ink were all developed at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in a place they call the Media Lab. It's a research lab and graduate school program that long ago outgrew its name. Today it's creating technologies to grow food in the desert, control our dreams and connect the human brain to the internet. Come have a look at what we found in a place you could call-- the Future Factory.

"The Media Lab is this glorious mixture, this renaissance, where we break down these formal disciplines and we mix it all up and we see what pops out."

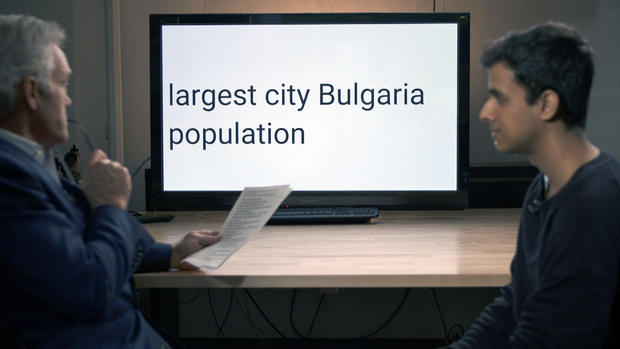

To Arnav Kapur, a graduate student in the Media Lab, the future is silent. He's developed a system to surf the internet with his mind.

Arnav Kapur: What happens is when you're reading or when you're talking to yourself, your brain transmits electrical signals to your vocal cords. You can actually pick these signals up and you can get certain clues as to what the person intends to speak.

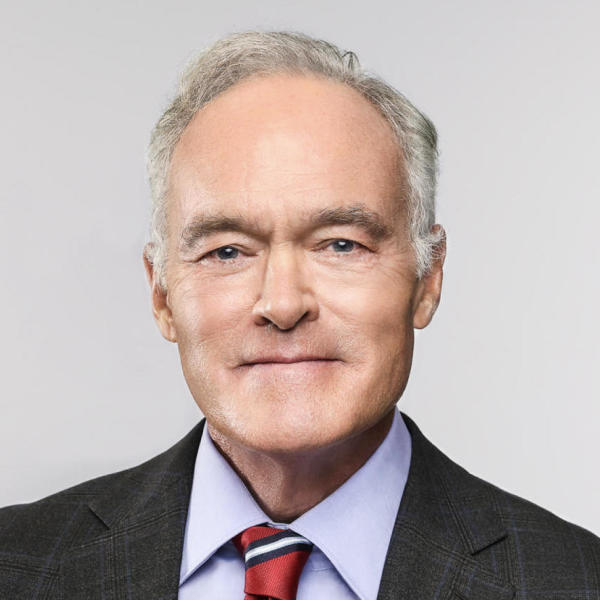

Scott Pelley: So the brain is sending an electrical signal for a word that you would normally speak but your device is intercepting that signal?

Arnav Kapur: It is

Scott Pelley: So instead of speaking the word, your device is sending it into a computer.

Arnav Kapur: That's correct.

Scott Pelley: That's unbelievable. Let's see how this works.

So we tried him.

Scott Pelley: What is 45,689 divided by 67?

Arnav Kapur: Sure.

He silently asks the computer and then hears the answer through vibrations transmitted through his skull and into his inner ear.

Arnav Kapur: Six eight one point nine two five.

Exactly right.

Scott Pelley: One more. What's the largest city in Bulgaria and what is the population?

The screen shows how long it takes the computer to read the words that he's saying to himself.

Arnav Kapur: Sofia, 1.21 million.

Scott Pelley: That is correct. You just Googled that.

Arnav Kapur: I did.

Scott Pelley: You could be an expert in any subject. You have the entire internet in your head.

Arnav Kapur: That's the idea.

Ideas are the currency of MIT's Media Lab. The lab is a six-story tower of Babel where 230 graduate students speak dialects of art, engineering, biology, physics and coding, all translated into innovation.

Hugh Herr: The Media Lab is this glorious mixture, this renaissance, where we break down these formal disciplines and we mix it all up and we see what pops out. That's the magic, that intellectual diversity.

Hugh Herr is a professor who leads an advanced prosthetics lab.

Scott Pelley: And what do you get from that?

Hugh Herr: You get this craziness. When you put, like, a toy designer next to a person that's thinking about what instruments will look like in the future next to someone like me, that's interfacing machines to the nervous system, you get really weird technologies. You get things that no one could've have conceived of.

"We really select for people who have a passion. We don't have to tell them to work hard. We have to tell them to work less hard and to get sleep, occasionally."

The Media Lab was conceived in a 1984 proposal. MIT's Nicholas Negroponte wrote "computers are media" that will lead to "interactive systems." He predicted the rise of flat panel displays, HD TVs and news "whenever you want it." Negroponte became co-founder of the lab and its director for 20 years.

Nicholas Negroponte: When we were demonstrating these things in, let's say, '85, '86, '87-- it was really considered new.

Scott Pelley: It looked like magic.

Nicholas Negroponte: Indistinguishable from magic.

In 1979 MIT developed "movie map" which predated Google street view by decades.

Now, notice what's so common today that you didn't even notice it. He's touching the screen. If you had seen that on 60 Minutes in the '80's, you would you have been amazed. And you might have been dazzled by one of the earliest flat screens.

Nicholas Negroponte: It was six inches by six inches, black and white it was a $500,000 piece of glass.

Scott Pelley: It cost a half a million dollars?

Nicholas Negroponte: It cost half a million dollars. I said, "that piece of glass will be six feet in diagonal with millions of pixels in full color.

In 1997, the lab also gave birth to the grandfather of Siri and Alexa.

And in 1989, it created turn-by-turn navigation that it called 'Back Seat Driver.'

Nicholas Negroponte: And the MIT patent lawyers looked at it and said, "This will never happen, never be done, because the insurance companies won't allow it so we're not gonna patent it."

Look through the glass walled labs today and you will witness 400 projects in the making. The lab is developing pacemaker batteries recharged by the beating of the heart, self-driving taxi tricycles that you summon with your phone, phones that do retinal eye exams and teaching robots.

Pattie Maes: So we think that the devices of tomorrow have an opportunity to do so much more and to fit better in our lives.

Professor Pattie Maes ran the graduate program's student admissions for more than a decade.

Pattie Maes: We really select for people who have a passion. We don't have to tell them to work hard. We have to tell them to work less hard and to get sleep, occasionally.

Scott Pelley: How often does a student come to you with an idea and you think, "We're not gonna do that?"

Pattie Maes: Actually, for us, the crazier the better.

Adam Haar-Horowitz' idea was so nutty he was one of 50 new students admitted last year out of 1,300 applications.

Adam Haar-Horowitz: I was really interested in a state of sleep where you start to dream before you're fully unconscious. Where you keep coming up with ideas right as you're about to go to sleep.

Haar-Horowitz' system plants ideas for dreams

Then records conversations with the dreamer during that semi-conscious moment before you fall asleep.

Her origami pyramid dream was influenced by the robot saying the word "mountain." It's long been believed that this is the moment when the mind is its most creative —Haar-Horowitz hopes to capture ideas that we often lose by the next morning.

Adam Haar-Horowitz: So it's basically like a conversation. You can ask, "Hey, Jibo, I'd like to dream about a rabbit tonight." It would watch for that trigger of unconsciousness. And then right as you're hitting the lip, it triggers you with the audio. it asks you what is it that you're thinking about. You record all that sleep talking. And then later, when you wake up fully, you can ask for those recordings.

Scott Pelley: And when he brought this idea to you, what did you think, really?

Pattie Maes: Crazy enough.

Nearby, in Hugh Herr's lab, Everett Lawson's brain is connected to his prosthetic foot—a replacement for the club foot he was born with.

Everett Lawson: The very definition of a leg, or a limb or ankle is gonna dramatically change with what they're doing. It isn't just whole, it's 150%.

Hugh Herr: You feel directly corrected?

Everett Lawson: Yeah, when I fire a muscle really fast, it makes its full sweep.

Herr's team has electronically connected the computers in the robotic foot with the muscles and nerves in Lawson's leg.

Hugh Herr: He's not only able to control via his thoughts. He can actually feel the designed synthetic limb. He feels the joints moving as if the joints are made of skin and bone.

For Professor Herr, necessity was the mother of invention. He lost his legs to frostbite at age 17 after he was stranded by a winter storm while mountain climbing.

Hugh Herr: Through that recovery process, my limbs are amputated, I design my own limbs, I return to my sport of mountain climbing I was climbing better than I'd achieved with normal, biological limbs. That experience was so inspiring 'cause I realized the power of technology to heal, to rehabilitate, and even extend human capability beyond natural, physiological levels.

Scott Pelley: You developed the legs that you're wearing today?

Hugh Herr: Each leg has three computers, actually, and 12 sensors. And they run these computations based on the sensory information that's coming in. And then what's controlled is a motor system, like muscle, that drives me as I walk; enable me to walk at different speeds.

Scott Pelley: What will this mean for people with disabilities?

Hugh Herr: Technology is freeing. It removes the shackles of disability from humans. And the vision of the Media Lab is that one day, through advances in technologies, we will eliminate all disability.

The current director of the Media Lab is Joi Ito—a four-time college dropout—and one of those misfits that the lab prefers. After success in high tech venture capital, he came here to preside over the lab's 30 faculty and a $75 million annual budget.

Scott Pelley: How do you pay for all this?

Joi Ito: So we have 90 companies that pay us a membership fee to join the consortium. And then because it's all coming into one pot, I can distribute the funds to our faculty and students, and they don't have to write grant proposals, don't have to ask for permission. They just make things.

Scott Pelley: Do any of these companies lean on you from time to time, and say, "Hey, we need some product here."

Joi Ito: They do. I've fired companies for that.

Scott Pelley: You fired them.

Joi Ito: yeah, I've told companies, you're too bottom-line oriented. Maybe we're not right for you.

The sponsors which include Lego -- the toy maker, Toshiba, ExxonMobil and General Electric, get first crack at inventions. The lab holds 302 patents—and counting.

Caleb Harper's idea is so big it doesn't fit in the building. So MIT donated the site of an abandoned particle accelerator for this trained architect who is now building farms.

He calls these "food computers"-- farms where conditions are perfect.

Caleb Harper: They're all capable of controlling climate. So they make a recipe. This much CO2, this much O2, this temperature. So we create a world in a box. Most people understand if you say, oh, the tomatoes in Tuscany on the north slope taste so good, and you can't get 'em anywhere else. That's those genetics under those conditions that cause that beautiful tomato, so we study that inside of these boxes with sensors, and the ability to control climate.

Scott Pelley: Tuscany in a box.

Caleb Harper: Tuscany in a box, Napa in a box, Bordeaux in a box.

Scott Pelley: Now these are plants you're growing in air.

These basil plants grow, not in soil--but in air.

Caleb Harper: The plant is super happy.

Scott Pelley: No dirt.

Air saturated with a custom mix of moisture and nutrients. The food computers grow almost anything, anywhere.

Scott Pelley: What have you learned about cotton farming?

Caleb Harper: So cotton is actually a perennial plant, which mean it would grow, you know, the whole year-long but it's treated like an annual. We have a season. So in this environment, since it's perfect for cotton, we've had plants go 12 months.

Scott Pelley: So how many crops can you get in a controlled environment like this one?

Caleb Harper: You can crop up to four or five seasons. We're growing, on average, three to four times faster than they can grow in the field.

The uncommon growth of the Media Lab flows from its refusal to be bound to goals, contracts, or next quarter's profits. It is simply a ship of exploration going wherever a crazy idea may lead.

Hugh Herr: We get to think about the future. What does the world look like, 10 years, 20 years, 30 years? What should it look like? You know, the best way to predict the future is to invent it.

Produced by Katie Kerbstat. Associate producer, Alex Diamond.