In Mississippi, a local race with national stakes

To many voters words like "establishment" or "populist" are just labels, at best. They're frustrated with everyone in Washington and don't much like either party, period. But contests like the Mississippi Republican Senate primary runoff Tuesday help define what the parties are in the first place: their direction - and response to that gridlock - isn't set by dictate from central headquarters (much as they sometimes try) but rather by one candidate in one race at a time.

Sen. Thad Cochran and state Sen. Chris McDaniel are both conservatives by just about any objective

measure, but the proxy fight here is whether tea party or traditional ("establishment") conservatives hold more sway over the Republicans.

Tuesday's runoff is happening only because McDaniel failed to secure the GOP nomination during the June 3 primary by scoring under 50 percent of the vote, forcing Tuesday's second vote. Cochran held McDaniel to only 49.5 percent of the vote (Cochran received 49.o percent and "lost" by less than 1,400 votes, out of over 313,000 votes cast).

Cochran is running as the establishment candidate; though Washington is unpopular there's really no choice for him but to embrace a tenure that stretches back to 1978 - and to remind voters that his seniority helps channel needed resources to Mississippi specifically. He's got heavy financial backing from traditional Republican groups like the Chamber of Commerce as well as high-profile endorsements from prominent Mississippians.

If Cochran wins, the conventional wisdom will collectively and knowingly nod that politics is still local, and chalk up another win for establishment pushback in a year when all the sitting Republican senators have easily beaten back challenges.

If he loses, we'll say those endorsements and spending only reminded voters of the entrenched politics that McDaniel decries. For McDaniel, his tea party-oriented campaign elicits more national focus, an opposition to federal spending more generally, and is as much about Washington as as about Cochran. In that sense, it hews to the tea party and movement conservatives' broader approach we've seen in other races, with candidates campaigning on a legislative style that would look to staunchly oppose Democrats at every turn, and less willing to cut deals. In either case, the race will probably serve as a referendum on both the local-versus-national dynamic, and that approach to governance.

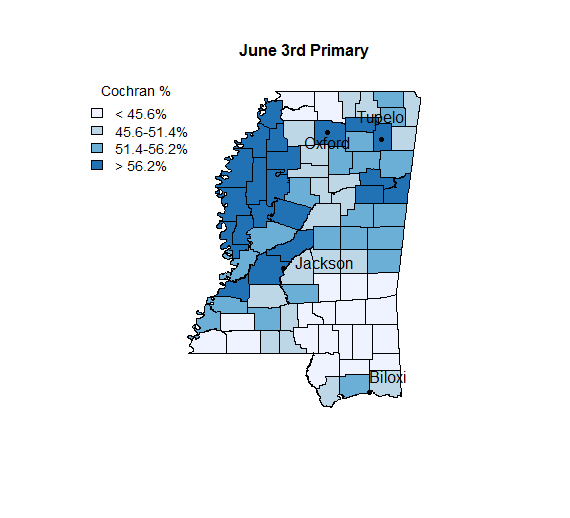

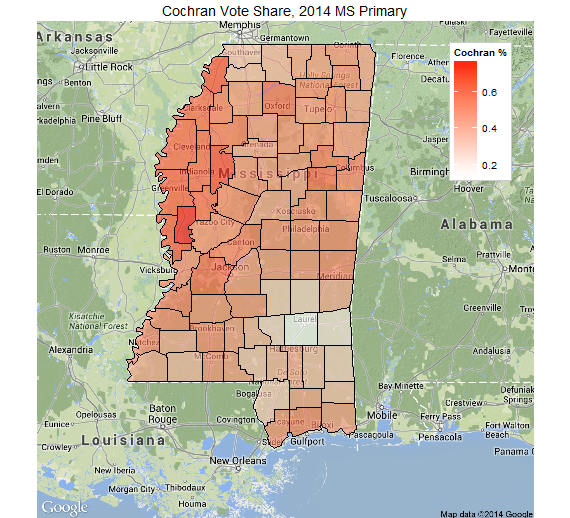

As votes come in Tuesday night, one way to watch this is to keep an eye on the cities. Cochran needs to do well around Jackson, the state capital. Also watch Hinds, Rankin and Madison counties, the largest and therefore among the most important to him. Lee County, up around Tupelo, is also critical.

Without margins in these places, he'll be in trouble; though the pattern is better described as necessary but not sufficient. Cochran carried four of the five counties casting the largest number of votes three weeks ago; but only one of the next five largest.

To a lesser extent, watch the Mississippi Delta (Washington County and then Warren County, or the city of Vicksburg) which tilted toward Cochran in the initial primary, though many in the region are smaller counties that aren't enough alone to carry the state.

McDaniel tended to do better across south central Mississippi and down toward the Gulf Coast. The latter region could be pivotal: this area was hit badly by Hurricane Katrina and Cochran's campaign has emphasized his efforts to get federal funding into the region, perhaps the most prominent example of that seniority-pays-off theme. If that finds resonance, it should be here, if anywhere.

In the initial primary Cochran won in the area immediately around the cities of Biloxi and Gulfport and Harrison County, but McDaniel carried Jackson County and most of the other smaller counties in the region.

Vote reporting in Mississippi has tended to happen well after the polls close at 8 p.m. ET - as late as 11 p.m. ET or later.

All elections are "about" turnout but summer primaries are especially so. You're asking voters to tune in once and then, in this case - having settled nothing - asking them to tune in and turn out again.

In one school of thought, the runoff system is a guard against a quirk or an unexpected upset, or makes sure a candidate has the most solid backing of their partisans. But it can also conceivably have the effect of giving the most committed and most ideological voters more sway, while less passionate ones stay home. The fact is we don't have a lot of examples and data to go on; it's not like there are a lot of these long-time-incumbent-forced-into-a-runoff stories. (The most recent comparable race we have is from Texas last cycle, but even that one isn't exact because there wasn't an incumbent, just an "establishment" favorite, which isn't the same thing. In that one, turnout did go down and Ted Cruz emerged the winner in what turned out to be a large show of leverage for the tea party.)

If relatively lower turnout skews toward the most-committed voters, who in turn tend to be the ones most fervently against anything they perceive as status quo, that in turn would probably favor McDaniel as the challenger here. Hence, you see the Cochran campaign trying to activate and motivate voters as much as possible.

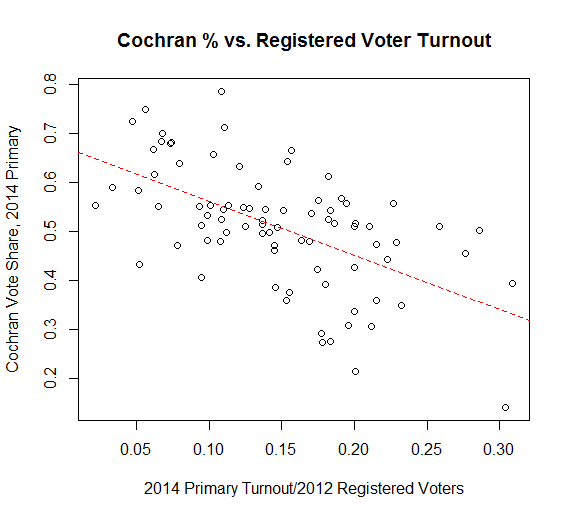

On the other hand, in the initial primary, Cochran's vote wasn't strongly correlated with turnout by county at all. To the extent there was any relationship, he may have done a little less well as turnout went up as a percent of registered voters. (Mississippi doesn't have partisan registration, which makes it harder to identify solid Republicans as well.)

The Polls

The publicly-released polls we've seen have it close; the initial primary was too so maybe that shouldn't surprise. The potential trouble with any polls at this time of year rests partly on the definition of likely voter. In high-turnout elections like presidential years, pinning down who is voting can be tricky enough, but because most registered voters do turn out for those, a pollster can err on the side of expected turnout and sometimes do okay. Low-turnout races like this one add difficulty because probably one-fifth or so of possible voters, at best, will really show up - perhaps well short of that, even, so making sure one accounts for just those voters - and no one else - gets harder still.

That's not necessarily a sampling issue, either, but one where "real life" gets in the way: in the summertime people have more going on; more activities with kids or family that run long, perhaps, more distractions that can turn a truly intentioned voter who answers a poll into a non-voter quickly, between the time they take the poll and Election Day.

Similarly, there's more room for campaigns to try to change the equation and persuade non-voters - of whom, there are many - to turn out after all. Finally, pollsters can often rely heavily on vote history to help guide them, because habitual voters tend to show up again and again. But vote history doesn't help predict as much when elections are rare, like this one; it isn't everyday a sitting senator ends up in a primary let alone a runoff.

The last three election cycles offer plenty of reminders of how much single-state races in spring- and summer- primaries like this one matter to national politics. Think again of Cruz - now nationally influential - winning the Republican nomination in a 2012 Texas runoff, or Rand Paul upsetting the "establishment" favorites in Kentucky in 2010. And of course, it all comes on the heels of House Majority Leader Eric Cantor's loss two weeks ago, which stunned the political world.

The implications tonight are indeed more about the Republicans than the state in November. In 2014, the narrative just weeks ago was that he "establishment" (meaning long-time incumbents and more business-backed conservatives) was on a winning streak pushing back against just this sort of thing: Sens. Mitch McConnell and Lindsey Graham easily beat back tea party insurgencies. Democrats would like to think that can happen here, too, but the state seems far safer territory for Republicans in the fall no matter what happens Tuesday night.