CBS News analysis: Voting changes get mixed reviews; many voters of color worry restrictions make things harder

Coming off a year of record turnout, we know most people are generally resistant to change, but what about some of the specific changes being debated in legislatures now, like voter ID, or what to do with mail ballot rules, drop boxes and voting times? So we asked people — and paired their views with their actual voting experiences last year.

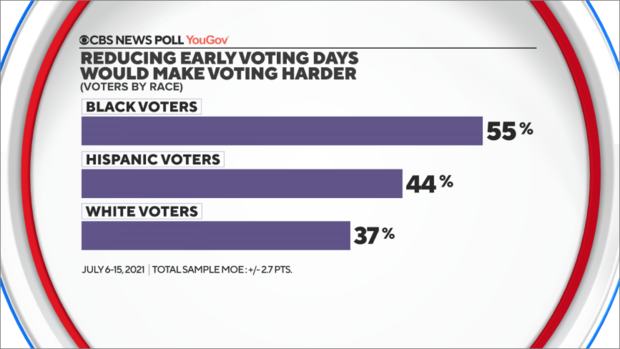

There's opposition to some, though not all, of the proposed voting changes, and the opposition isn't just based on principle — it's personal for many. Some voters of color feel their own voting experience will become harder. Many of them voted early and used drop boxes in 2020, and our analysis of public records and voter file data lends credence to their concerns.

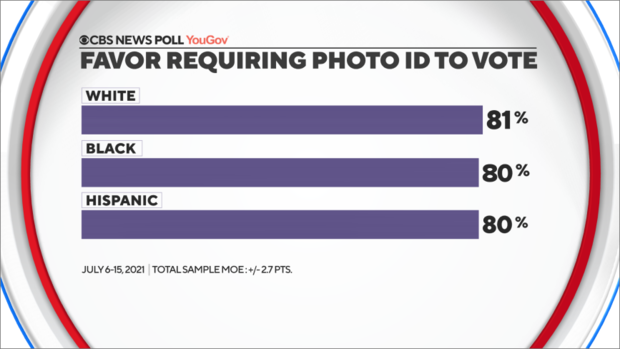

On the other hand, there are other items like voter ID that do find widespread support, from voters of color as well as White voters, and across party lines, too.

Overall, most 2020 voters already call their last experience "very easy" or "easy," which may explain their general resistance to change. All our survey findings come from data that includes validated voters, meaning public records show they actually turned out.

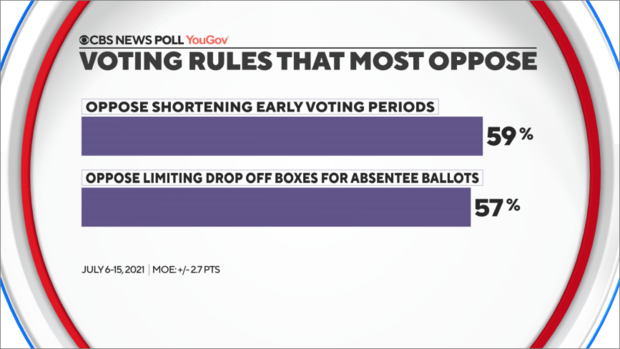

Most oppose restricting early voting

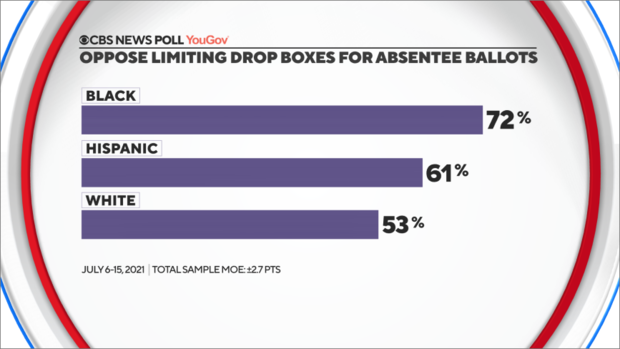

A record number of people voted before Election Day in 2020, and most don't want to see early voting rules more restricted. Majorities oppose both shortening early voting periods and limiting the number of drop boxes for absentee ballots, which some state legislatures have done.

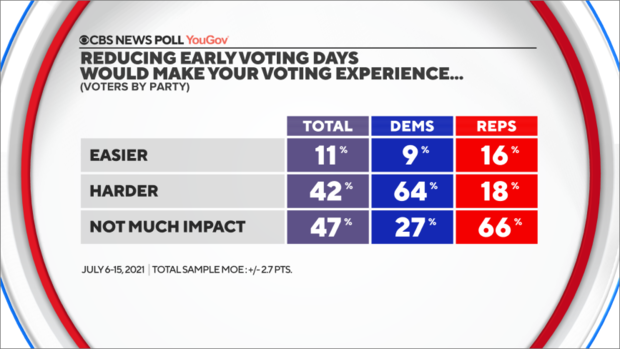

In 2020, Democrats and Republicans voted early in-person in similar numbers, but Democrats are more likely to say their voting experience would be made harder if early voting days were cut down. While most Republicans support these measures, Republicans who voted early in 2020 are less supportive.

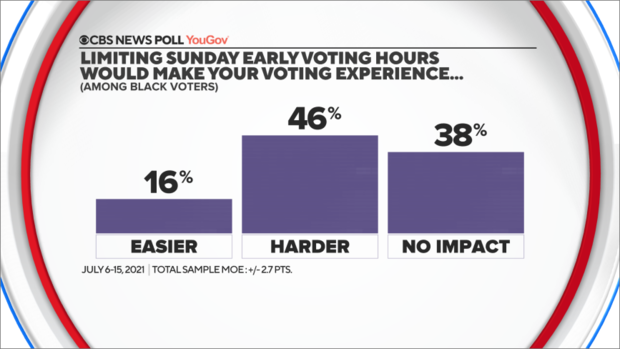

Early voting on Sunday in particular is popular among Black voters, a key Democratic voting group. And by about three to one, Black voters say if those voting hours were limited that would make it harder, not easier, for them to vote. In Texas, a provision that would have shortened the hours available for Sunday early voting has been omitted from the current bill under debate.

Impact of absentee voting rules

In fact, public records bear out the voting patterns that underlie these concerns in key states. For instance, an analysis of Georgia's voter file reveals that the state's 2020 absentee voters are 7 percentage points more likely to be Black than Election-Day voters are. Moreover, Black voters are especially at risk of having their ballots rejected, even before added requirements for voting by mail. About half of the rejected ballots were from Black voters, even though they make up just a third of the electorate.

Several states are reducing the number of ballot drop boxes available in ways that are likely to have a larger impact on more densely populated and Democratic leaning areas. Georgia's law mandates only one drop box per 100,000 voters. That would mean that populous Cobb County would go from 16 boxes last fall to just five, Fulton County from 38 to 8, and Metro Atlanta from 94 to 23. Millions used these boxes to vote early in 2020, including most absentee voters Cobb and Fulton, as well as over 1.5 million voters in Florida.

In Iowa, a new law limits counties to a single drop box each. This would mean the largest nine counties — which altogether accounted for about half of the state's votes in 2020 — would get the same number of drop boxes as the other 90 counties. In the first group, there would be over 90,000 voters per drop box. In the second, closer to 9,000.

Given this, it's not surprising that Black Americans nationwide express greater opposition to limiting drop boxes than White people do. Opposition also rises from just over half of those in the suburbs to about two-thirds in cities.

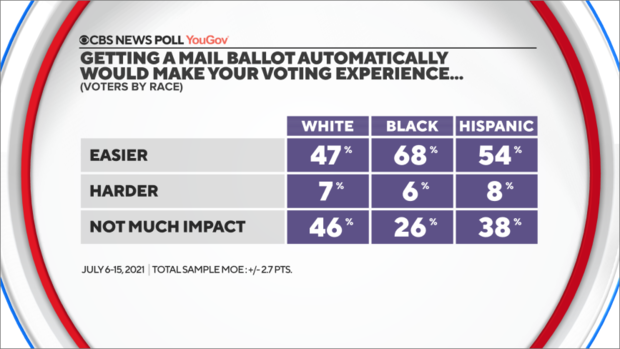

In some states and counties voters automatically received a mail ballot without requesting one. Some new measures would curtail that practice. Last year, mail ballots in general — whether mailed directly or requested — were used disproportionately by voters of color, and they are more likely than White voters to say that automatically receiving a mail ballot would make the process easier for them.

Partisanship is heavily connected to views on mail balloting, but so is personal experience. Republicans who voted by mail in 2020 are twice as likely as Republicans who voted in person to say automatically receiving a ballot would make voting easier for them.

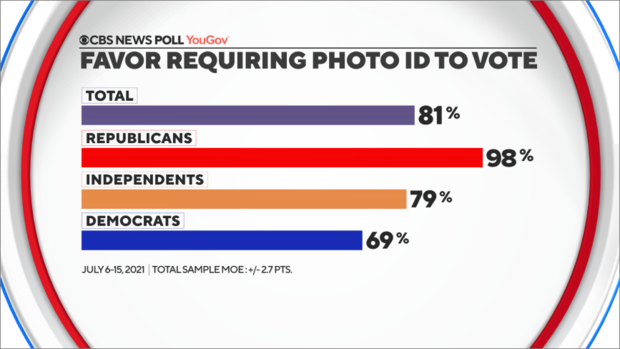

Widespread support for voter ID

Large majorities across political lines, age, and racial groups favor requiring photo ID to vote. One reason few see it as a barrier to participation is that 93% of American adults and 97% of registered voters report having valid photo identification, like a driver's license or U.S. passport.

Even among those who generally want to make voting easier, six in 10 support voter ID. Actual 2020 voters (96%) are somewhat likelier than non-voters (87%) to support the policy.

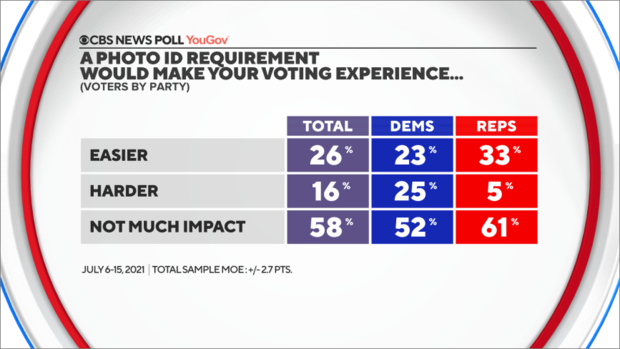

Compared to other proposals, like shortening early voting periods and limiting the availability of early voting hours on Sunday, fewer voters say showing photo ID to vote would personally make it harder for them to vote. Most say it wouldn't have much impact, with the remainder more likely to say it would make their experience easier than harder.

Scholarly studies find that while many voters are asked to provide ID at the polls, very few say they were subsequently denied a vote. A recent historical study looking at 2008-2018 finds that voter ID laws do not negatively impact registration or turnout — overall or within racial groups.

But some studies suggest the policy can still have a bigger effect on some people than others, even if the topline impact isn't sweeping. Studies show voters of color may be disproportionately affected. They are less likely than White voters to have government-issued photo identification, such as a valid driver's license or U.S. passport. Moreover, election poll workers have lots of discretion in enforcing these rules, often asking voters of color for more stringent identification.

It may also take more effort and resources for political campaigns or parties to navigate the new rules, and studies show they do try. This involves what's called counter-mobilization. That can happen when a policy elicits strong backlash and/or organizing efforts. The aforementioned historical study, for example, finds that when voter ID laws are enacted, voters of color are more likely to be contacted by political campaigns, which send out information and encouragement to vote.

Still, one in six registered voters nationwide feel that this requirement would make voting harder for them. Democrats and independents are much likelier than Republicans to say so, and younger voters likelier than older ones.

Other popular measures

And there is also majority support for policies such as automatic registration for eligible voters, sending all eligible voters a mail ballot, and allowing Election-Day registration — all of which are likely to boost participation if enacted in more states.

Research on the effects of automatic voter registration has shown that it increases registration and turnout rates, and implementing it in more states is projected to substantially increase registration, without clearly benefiting either party. Election-Day registration, also known as same day registration, also has a positive effect on turnout, especially among younger voters. And a recent study finds that all-mail voting in Colorado also increases turnout with bigger gains among low-propensity voters.

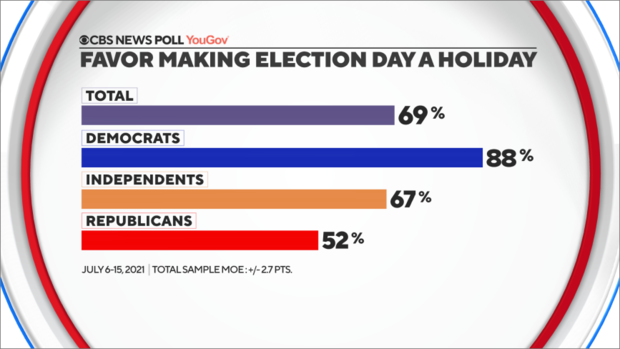

Another item tested that gets bipartisan support has little to do with the ins and outs of voting rules and procedures: most support making Election Day a federal holiday.

Most Democrats, independents and a slimmer majority of Republicans favor that. By more than 10 to 1, voters say if election day was a holiday it would make it easier, rather than harder, for them to vote.

This is part of a series of reports from a new CBS News study on America's elections and voting process. The study is based on several data sources: a national survey, voter file data, and certified election results. The survey includes an oversample of over 2,000 validated voters who were matched to voter files confirming their vote history. We also reference academic work and data journalism by other researchers on voting rights and election administration.

The survey was conducted by YouGov using a nationally representative sample of 2,664 U.S. residents interviewed between July 6-15, 2021. Of the 2,065 self-reported voters in the sample, 2,023 were matched to voter files and confirmed as having voted. The sample was weighted according to gender, age, race and education based on the American Community Survey, conducted by the U.S. Bureau of the Census, as well as the 2020 presidential vote and registration status. The margin of error is ±2.7 points for the total sample.