It's been a record 11 years since the last increase in U.S. minimum wage

It's been 11 years since the last federal minimum wage hike, the longest span the baseline wage has gone without an increase since it began in 1938.

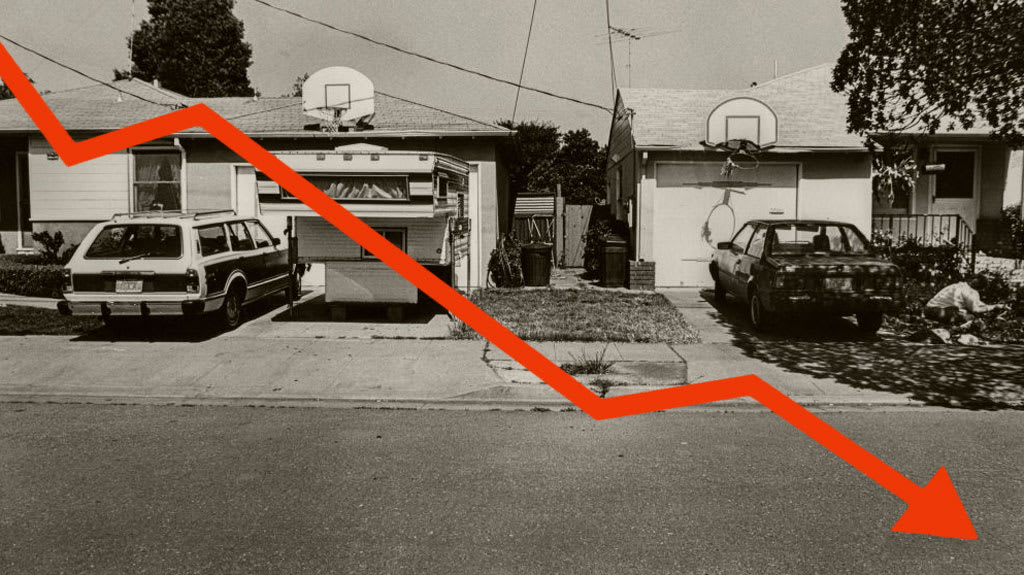

Since the last federal minimum wage hike — to $7.25 an hour, starting July 24, 2009 — the cost of living has increased 20%, while the price of essentials such as housing and health care have increased even faster. That left many low-wage workers with little financial flexibility or savings as pandemic hit the nation this year and swiftly resulted in a recession and double-digit unemployment.

The average rent back in 2009 was about $1,132, adjusted for inflation. But housing costs have soared in the past decade, pushing the average rent to almost $1,470 in February — or almost 30% higher than the typical rent in 2009, according to the latest RENTCafe report.

Today, a worker must earn almost $20 an hour to afford a modest one-bedroom apartment, according to a July study from the National Low Income Housing Coalition.

The push for a higher federal minimum wage may have been shoved to the backburner amid the widespread impact of the coronavirus pandemic, with lawmakers focused on the next stimulus bill and extending $600 a week in extra federal unemployment benefits for 25 million out-of-work adults. But advocates for a higher minimum wage say it's time for a bump in the federal baseline wage, given the struggles that lower-income workers are facing in the crisis.

"Even in these tough times, I wouldn't consider lowering wages, because my talented employees are at the heart of my business success and I can't afford to lose them," Michael O'Connor, the owner of barber shops in Philadelphia and Jenkintown, Pennsylvania, and a member of the advocacy group Business for a Fair Minimum Wage, said in an emailed statement. "People can't spend money at local businesses like mine if they don't have it, which is why raising the minimum wage is all the more important now."

Income losses

About 6 of 10 workers who earn less than $25,000 a year have suffered a loss of income since March, according to the Census household pulse survey. By comparison about 3 in 10 people who earn more than $200,000 have lost income since the pandemic began.

To be sure, it may seem counterintuitive to raise the minimum wage during an economic crisis, but Holly Sklar, the CEO of Business for a Fair Minimum Wage, pointed out that the minimum wage was "enacted to help our country recover from the Great Depression by lifting insufficient wages and boosting the consumer buying power that businesses depend on to survive and grow."

During the past several years, dozens of states and municipalities have passed local laws to boost their baseline wages. But 21 states have either no minimum wage law or baseline wages that match the federal $7.25 an hour, according to the U.S. Department of Labor.

The longest span without an increase before the current one was in the 1980s, when the minimum wage remained at $3.35 an hour from 1981 until 1990.

The extra $600 in unemployment benefits, enacted by the CARES Act to help workers laid off due to the coronavirus crisis, has refocused the debate about wages.

Many Republican lawmakers argue that the extra benefit is too high, in some cases paying people more than they earned while working. Their argument: Lower-paid workers won't want to return to their jobs because they can make more on unemployment.

But that doesn't appear to be the case, according to a recent study from Yale economists. Instead, workers receiving the extra $600 per week "have returned to their previous jobs over time at similar rates as others," the noted.