Mind-guided robotic arm lets paralyzed man touch girlfriend

(CBS/AP) A paralyzed man from Pennsylvania put his new thought-controlled robotic arm through its paces recently, using it to reach out and touch his girlfriend's hand.

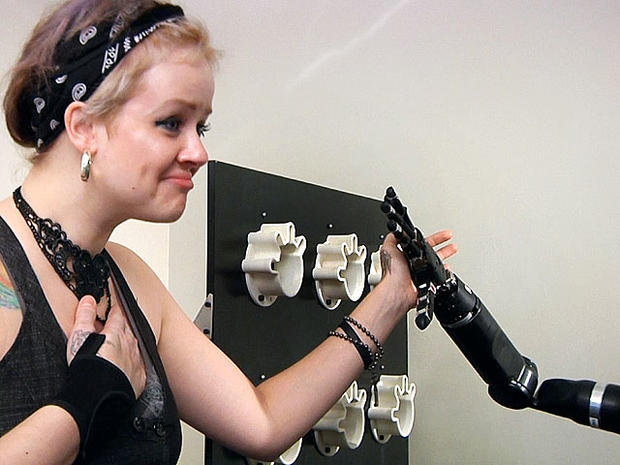

PICTURES: Robotic arm lets paralyzed man touch girlfriend

"It wasn't my arm but it was my brain, my thoughts. I was moving something," said Tim Hemmes, 30, who became a quadriplegic seven years ago after a motorcycle accident. "I don't have one single word to give you what I felt at that moment. That word doesn't exist."

Hemmes - whose emotional moment came during a month-long experiment at the University of Pittsburgh - is among the pioneers in an ambitious quest for thought-controlled prosthetics. The ultimate goal is to give paralyzed people greater independence - the ability to feed themselves, turn a doorknob, hug a loved one.

The robotic arm is considered the most humanlike bionic arm to date - even the fingers bend like real ones. It's controlled by electrical signals from tiny brain electrodes implanted into the brain.

The research is years away from commercial use, but numerous teams are investigating different methods. At Pittsburgh, monkeys learned to reward themselves with marshmallows by thinking a robot arm into motion. At Duke University, monkeys used their thoughts to move virtual arms on a computer and got feedback that let them distinguish the texture of what they "touched."

Through a project known as BrainGate and other research, a few paralyzed people outfitted with brain electrodes have used their minds to use computers and make simple movements with prosthetic arms.

But can these so-called neuroprosthetics ever provide the complex, rapid movements that people need for practical, everyday use?

"We really are at a tipping point now with this technology," says Michael McLoughlin of the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory, which developed the humanlike arm in a $100-million project for DARPA, the Pentagon's research agency.

Pittsburgh is helping to lead a series of government-funded studies over the next two years to try to find out. A handful of quadriplegic volunteers will train their brains to operate the DARPA arm in increasingly sophisticated ways, even using sensors implanted in its fingertips to feel what they touch, while scientists explore which electrodes work best.

Hemmes surprised researchers the day before the electrodes were removed. The robotic arm whirred as Hemmes' mind nudged it forward to hesitantly tap palms with a scientist. Then his girlfriend beckoned. The room abruptly fell silent as Hemmes painstakingly raised the black metal hand again and slowly rubbed its palm against hers.

"It was awesome," is how the normally reserved Dr. Michael Boninger, rehabilitation chief at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, described the moment. "To interact with a human that way. ... This is the beginning."