Military vehicle training accidents, many fatal, reveal faulty equipment, poor training

Last month, two Marines were killed and 17 injured – not in war, but in transit: their truck flipped over on a highway outside of Camp Lejeune, North Carolina. And it's not as uncommon as you'd think. We found that as a parent or partner of someone in the military, you're far likelier to get that dreaded "call" and learn your loved one was killed in an accident, rather than in combat. And many - far too many - of the accidents involve armored vehicles during training.

First Lieutenant Conor McDowell, a platoon leader in the Marines, was out on a training mission in a light armored vehicle at Camp Pendleton, California, in May 2019, when he hit an unmarked ditch covered in brush.

Lesley Stahl: Describe what happened.

Susan Flanigan: He called out to his men, "rollover, rollover, rollover" pushed his gunner in the turret next to him down under the armor but he couldn't get himself down in time and it careened into that ditch, rolled over, and crushed him.

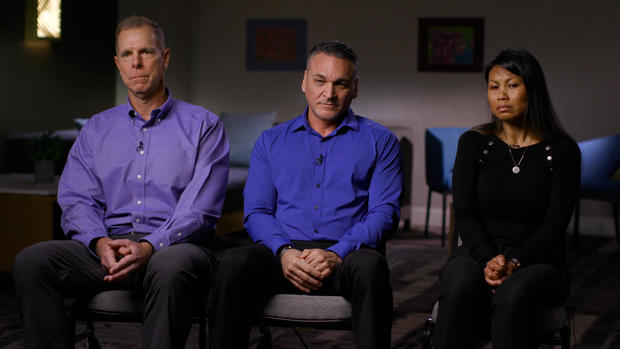

Conor was Susan Flanigan and Michael McDowell's only child.

Michael McDowell: At first I thought that this was what happens when you train like you mean to fight. But when we went to San Diego to bring him back I had a couple of idle moments in the hotel. And I Googled "rollover" and "military." And I discovered that at Pendleton a month before, a Marine raider had died in a rollover. So I Googled further back, "the Army," et cetera. And suddenly I saw a whole series of deaths in rollovers of military vehicles, all kinds: Humvees, Light-Armored Vehicles, Bradley Fighting Vehicles. And then I realized this is not a single incident. This is a systemic problem.

Lesley Stahl: During training?

Michael McDowell: During training. I can accept people dying in combat. But if you're training in your own country and you're dying needlessly in preventable accidents, this is a massive problem which has to be fixed.

To fix it, McDowell kept digging and what he uncovered, he says, was so serious and yet so routinely neglected that it led to a scathing report by the Government Accountability Office: the GAO found close to 4,000 of these accidents in the Army and Marine Corps from 2010 to 2019, resulting in 123 deaths, nearly two-thirds of which involved rollovers. And shockingly: most occured in daylight, on regular roads, even in parking lots.

Michael McDowell: It's the tragedy of low expectations. That it's expected people will die in training.

Lesley Stahl: Are you saying that, that they expect this? What are you saying?

Michael McDowell: It's regarded as that's the price of being a soldier or a Marine.

Lesley Stahl: In training?

Michael McDowell: Yes.

Lesley Stahl: They expect–

Michael McDowell: "Training is dangerous. These things happen."

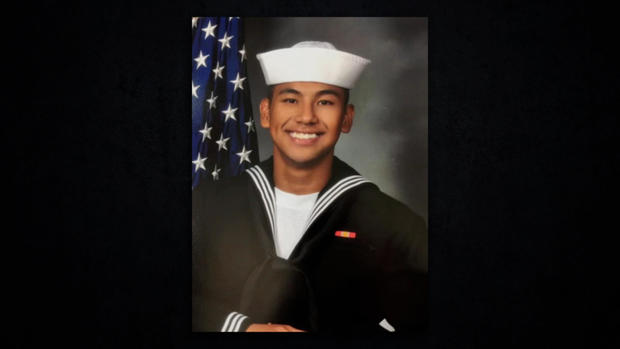

But they don't just "happen." The GAO concluded there was often "improper supervision". That drivers were poorly trained and vehicles - inadequately inspected. Some accidents involved multiple factors, as was the case with Christopher-Bobby Gnem, a Navy sailor.

There were screams of joy from Bobby's mom, Nancy, when he surprised her one Christmas.

A year and a half later, in the summer of 2020, he and 15 Marines were training off Camp Pendleton in Amphibious Assault Vehicles – or AAVs – giant armored vessels Marines used on both land and sea. His stepdad, Peter Vienna, says the Marines had no business sending out the AAVs used in his son's drill.

Peter Vienna: They're 40 years old and they were in terrible condition. And instead of asking for better condition AAVs, which there were-- there were plenty of them. they had gotten these, all of them that were in poor condition.

Peter Ostrovsky: So they're sitting in a parking lot on Camp Pendleton baking in the sun. They're deteriorating.

Peter Ostrovsky's son, Jack Ryan, was also on that mission.

Peter Ostrovsky: A week prior to the mission, we were speaking on the telephone. And he made the comment that "AAVs sink all the time." They've called them, and he called it a "floating coffin."

Lesley Stahl: Do you think he was worried?

Peter Ostrovsky: Oh, absolutely.

Two AAVs broke down and their sons' designated vehicle sprang an engine leak. And yet the mission was not aborted.

Lesley Stahl: What was the drive to go forward with faulty equipment?

Peter Ostrovsky: They're trying to keep a schedule. [To] stay on time.

Peter Vienna: The safety of our sons took a second place to completing a training mission. This isn't combat. This isn't "got to do it right now." This is training. There should have been an all stop at many points.

But 16 young men crowded into the AAV as seen in a video that one of the Marines sent his dad. It almost immediately started taking on water: ankle level; calf level; seat level, as one-by-one the AAV systems were failing.

Peter Vienna: The communication system was down. They were in the dark using their - the lights on their cell phones to try to see.

Lesley Stahl: Wait, wait, wait. The lights didn't work?

Peter Vienna: The safety lighting that's supposed to function - didn't function.

Lesley Stahl: Were there lifeboats?

Peter Vienna: No. So there's supposed to be two safety boats in the water. They went with none.

This is the AAV at the bottom of the ocean in underwater video we obtained through a freedom of information request. Seven men made it out alive. Nine did not. Turns out most had received little or no safety training on how to escape.

Lesley Stahl: It doesn't make sense.

Peter Vienna: There's so much of it that doesn't make sense. They were taking on water for 45 minutes yet they were still found at the bottom of the ocean with all their-- their gear still on, their body armor.

Lesley Stahl: And that-- they should not have—that should have come off?

Peter Vienna: They didn't know what to do. They were all looking at each other, like, "What does this mean, what do we do?"

Lesley Stahl: You know, the Marine Corps did its own investigation, and the Marine Corps concluded that this, and I'm going to use the direct quote, was "preventable."

Peter Ostrovsky: The top-down incompetence, the lack of readiness, Really the lack of duty of care for our sons-- it was shocking.

Lesley Stahl: Can you sue the military or the commanders for what happened?

Peter Vienna: There's the Feres doctrine - makes that impossible.

The Feres Doctrine prevents anyone from suing the military for anything that happens to service-members on the job, no matter how egregious.

Nancy Vienna: The biggest thing for me is, these boys were not protected. I have this vision in my head - nightmares of the AAV going down. What was his last word?

This was one of the worst training accidents in Marine Corps history. But accidents keep coming, and the GAO states less serious ones are likely under-reported. Christian Avila Taveras, an Army combat medic, was on a training drill in 2018 when one vehicle broke down so his vehicle had to tow it.

Christian Avila Taveras: This is around 1:30 a.m. maybe. It's dark, it's raining, it's muddy. The vehicle that we were towing just slid and hit us. And so we just rolled over. And I was expelled from the vehicle, and then the vehicle just landed on top of me, pinning me down from the waist down.

Lesley Stahl: So this giant monster vehicle rolls over on top of you?

Christian Avila Taveras: Yes. On top of me.

His left leg had to be amputated above the knee.The right leg was so badly damaged, he spent the next two years in rehab, learning how to walk again.

And we learned there was another rollover during training at that same place that same day as Avila Taveras's.

The Army told us there were fewer vehicle deaths last year, saying most are caused by human error and inexperience; nearly 1 in 5 enlistees join the Army with no driver's license.

The Pentagon and Marines declined our interview requests though the new defense budget mandates several new safety provisions, and AAVs will no longer be used in water drills.

But there are more steps the military could take that they haven't, involving relatively inexpensive upgrades to the vehicle involved in most accidents: the Humvee.

Test footage by IMMI, a safety system supplier, shows what can happen inside a Humvee in a rollover.

But watch: drivers could have a better chance when Humvees are retrofitted with IMMI's restraints and airbags.

One reason there are so many Humvee accidents is numbers: over 100,000 are used by the Army alone. Another cause is engineering: their high center of gravity makes them prone to flip-over.

And because humvees were easy targets for IEDs in Iraq and Afghanistan, the military added extra armor that made them even less stable.

We were invited by Ricardo Defense, a small military contractor, to suit up for a demo of how unstable these vehicles can be while making turns.

We were going less than 30 miles an hour. The two yellow bars were there to prevent us from actually tipping over.

Most Humvees do not have anti-lock brakes or electronic stability control that prevent rollovers. But eight years ago, Ricardo developed them for the Humvee. Ricardo's president is Chet Gryczan.

Chet Gryczan: Let's do the same thing with the system on, please?

With the system on: all wheels remained firmly on the ground.

The system works so well, it's now mandatory in all new Humvees. But what about Humvees already in use? Well, Ricardo came up with a safety kit that could be installed for about $16,000 per vehicle, in about 54,000 of the older Humvees.

You could make 10 or more old vehicles safer for the price of one new vehicle. And yet, the department of defense is asking for a lot of money for new Humvees, but only a fraction of what's needed to retrofit old ones.

Chet Gryczan: If the budget were to be approved today as the numbers stand, we would have enough funding for about 545 vehicles.

Lesley Stahl: 545 vehicles out of 54,000? That's it?

Chet Gryczan: That's it, yeah. So that's about 1% of the fleet. At that rate, it'll take 100 years to get the fleet fit.

Lesley Stahl: A recent letter to the Pentagon from several congressmen endorses your kit. They calculated that the difference in cost between putting your kit on and building a new vehicle is about $13 billion. It sounds like a no-brainer.

Chet Gryczan: Yeah. Why wouldn't you do it?

Chair of the Armed Services Subcommittee on Readiness, Congressman John Garamendi, told us that Congress and the Pentagon's preference for new over upgrades is "often predicated on keeping defense contractors fed."

Lesley Stahl: Have you made any move to say "nobody should be in a Humvee that doesn't have anti-lock brakes"?

Michael McDowell: We have tried and I have lobbied. We want to increase safety in training. Because people are dying needlessly in preventable accidents. It won't cost that much. But it's got to be done. And that's for the American people to press their members of Congress.

Produced by Shachar Bar-On. Associate producer, Jinsol Jung. Broadcast associate, Wren Woodson. Edited by Matthew Lev.