Doctors in Congress urge border officials to offer migrants flu shots

Three physicians serving in Congress are urging the Trump administration to scrap longstanding policy and ensure that detained migrant families, children and single adults can receive flu vaccinations while they're in Border Patrol custody.

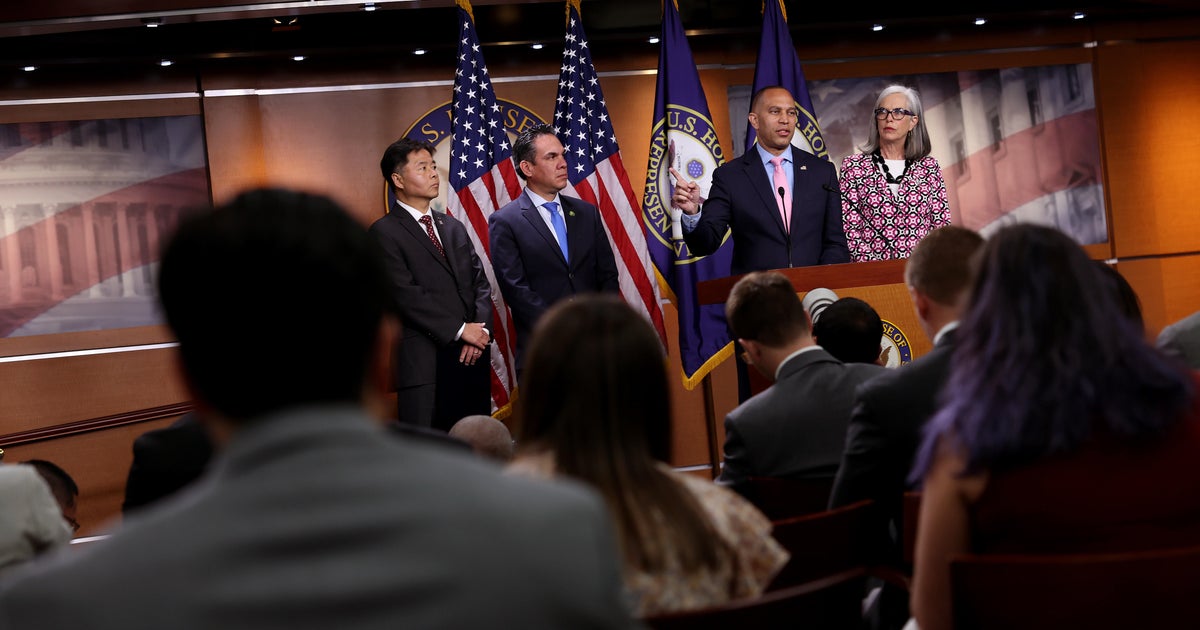

In a letter to Acting Homeland Security Secretary Kevin McAleenan and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention director Robert Redfield, Representatives Kim Schrier, Ami Bera and Raul Ruiz — the three doctors in the House Democratic Caucus — denounced the current policy of not providing vaccines to migrants detained by Border Patrol agents as "dangerous" and "shortsighted."

The trio of Democratic lawmakers said they are particularly concerned about the Customs and Border Protection (CBP) policy because at least three migrant children in U.S. custody have died of influenza infections in recent months. Autopsies revealed that 16-year-old Carlos Hernandez Vásquez, 8-year-old Felipe Gómez Alonzo and 2-year-old Wilmer Josué Ramírez Vásquez all died because of health complications due to the flu and other bacterial infections.

"Vulnerable populations, like children, the elderly and those who are chronically ill, are more susceptible to complications from the flu," they wrote. "And for a respiratory infection like influenza, risk increases when people are located within close quarters. That's why administering flu vaccines for people in contained areas is the gold standard to prevent complications and save lives."

Citing recommendations by the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP), the three lawmakers asked CBP and its medical contractors to provide flu vaccines to all migrants six months and older during their initial health screening.

Vaccinating detained migrants has never been a codified practice at CBP, an agency official told CBS News. The agency said this has been the case because of the "complexities of operating vaccination programs" and because Border Patrol agents, under both internal policy and U.S. law, try to detain migrants — especially children — for no more than three days before transferring them to other government agencies or releasing them.

"As a law enforcement agency, and due to the short term nature of CBP holding and other logistical challenges, operating a vaccine program is not feasible," the CBP official added.

But the official conceded that on some occasions, especially during upticks in families and children crossing the southern border, the agency has not been able to limit the detention of migrants in its custody to 72 hours.

For much of this year, a months-long surge of Central American families and children journeying to the U.S.-Mexico border led to reports of overcrowding and squalid conditions in facilities operated by CBP. Since a 13-year monthly high in May, border apprehensions have declined consistently during the subsequent months, reaching approximately 51,000 in August.

But Schrier, Bera and Ruiz said they are worried that another surge in the flow migrants could lead to more overcrowding in detention facilities and increase the chances of an outbreak.

"Given the overcrowded conditions at many CBP facilities, and the prolonged length of time that people are kept in these facilities, we urge you to follow these recommendations this flu season," they wrote.

CBP has maintained that agencies like Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) and the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) are better equipped to provide vaccinations, since they oversee more long-term detention of migrants.

If they are not released, most migrant families with children and single adults are transferred to ICE after being apprehended by Border Patrol. Under U.S. law, unaccompanied migrant children are supposed to be transferred to the care of HHS within three days of their apprehension by CBP.

An ICE official told CBS News that the agency does not routinely vaccinate everyone its custody but that it does offer vaccines against measles, mumps, the flu, varicella and other diseases upon request.

Because many of the migrants lack medical records and come from countries with different health standards than those in the U.S., the ICE official said it is difficult for the agency to determine who in its custody needs a vaccine.

"ICE has no way of knowing what medical issues a person may have or what illnesses they may have been exposed to prior to coming into custody, which is why each detainee is given an initial medical screening within 12 hours of arrival into ICE custody, followed by a comprehensive medical examination within 14 days," the official added.

The Office of Refugee Resettlement (ORR), the agency within HHS that takes care of unaccompanied migrant children, has a robust medical screening and care system in place. According to an HHS official, all children must receive a medical examination within two days of their admission into the agency's care. During the examinations, medical staff "assess general health, administer vaccinations in keeping with U.S. standards, identify health conditions that require further attention, and detect contagious diseases, such as influenza or tuberculosis."

Children who lack vaccination records or whose records are not current receive all vaccinations approved by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the HHS official said. Seasonal influenza vaccines are also administered to children who are in the agency's care for months.

Migrants who have the flu while in Border Patrol custody are either diagnosed and treated in the facility where they are detained or transported to a local clinic or hospital for treatment, the CBP official said. The agency said it makes "concerted efforts" to separate those who have the flu from other detainees.

Although it does not offer vaccinations, CBP said it has been expanding its team of medical contractors near the U.S.-Mexico border and currently has about 200 personnel. The agency said the team is prepared to provide care to pregnant women, children and other detained migrants.