Families separated by Trump administration at the border still waiting for reunification

It's been 35 years since Congress last passed a sweeping overhaul of the immigration system. So, president after president has careened from crisis to crisis at the border. President Biden is no different.

His administration is struggling to deal with one of the largest surges of migrants at the southern border in 20 years while, at the same time, trying to clean up another immigration mess you might think was already fixed.

Remember the stories of migrant children being intentionally separated from their parents at the border in 2018? The practice sparked widespread, bipartisan outrage and forced President Trump to order an end to the separations. Soon after, a federal judge ordered the government to reunite the families.

But three years later, at least a thousand children have not been returned to their parents.

We went to southern Indiana to meet two of those children from El Salvador. Jaime is 13. His brother Adonis is 9. In 2017, the boys and their mother crossed this bridge that links Mexico to the United States. The boys don't remember much about the trip, but Jaime has a vivid memory of when U.S. border officers took his mother away.

Sharyn Alfonsi: When they took your mom away, do you remember what she said to you?

Jaime: Yeah, she told me to be a strong brother, to help my brother and everything, to never feel bad… don't worry about what happened, worry about your brother.

Jaime and Adonis were among the first of nearly 4,000 children to be intentionally separated from their parents at the border as part of the Trump administration's zero-tolerance immigration policy. A federal judge ordered the government to reunite the families within 30 days. That was in 2018.

Sharyn Alfonsi: I think a lot of people will say to themselves, like, "How can they not have reunited these families already? There's parents and there's a kid, and you've gotta get them together." Why is it so difficult?

Michelle Brane: It's been three-plus years for a lot of these families. They have moved to different places. So they're no longer at the addresses we may have last had for them. They-- in many cases, these children are with sponsors who they now call mommy and daddy, right? And so it's not as simple as just saying, "Gonna put you on a plane, and reunify you, and then we're done."

Michelle Brane leads the family reunification task force formed by President Biden in the first weeks of his presidency. Four federal agencies are working on it, but despite their power and reach, in seven months, they've only reunited 52 families.

Michelle Brane: We estimate that over 1,000, somewhere between 1,000, 1,500 maybe more remain separated. It's very hard to know because there's no record.

Sharyn Alfonsi: How do you separate a child from their parents, and there's no documentation?

Michelle Brane: It is shocking. And really, what happened was that there was no system in place for documenting separations. So there's nowhere to go to find out who was separated or not. It really is case-by-case detective work.

A federal investigation described the government's record-keeping during child separations as "ad-hoc." One border station "used a basic whiteboard" to keep track of the children. Phone numbers, addresses and names for parents were missing. The federal judge who ordered the U.S. government in 2018 to reunite the families wrote, "migrant children are not accounted for with the same efficiency and accuracy as property."

Lee Gelernt: When I began investigating this did I think that, in 2021, I'd be sitting here in El Salvador, still looking for families, not in a million years. Looking back, maybe I was naïve.

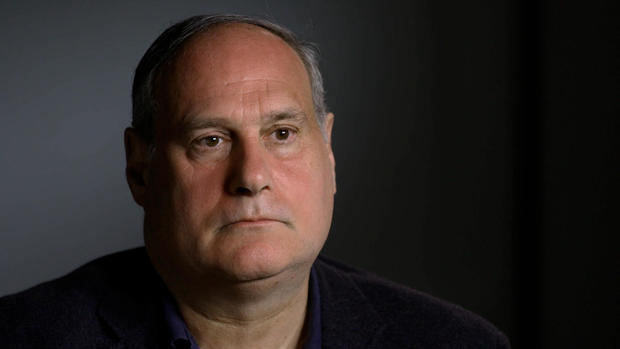

Lee Gelernt is a lawyer with the American Civil Liberties Union. We met him in Central America. Gelernt led the lawsuit to stop the practice of family separation.

For two years, he's been working with local teams to help find the parents that were separated from their children and then deported.

Lee Gelernt: When we got the first list of children and there were children under a year old, 6 months old, hundreds-- we were shocked. I mean, really shocked.

Sharyn Alfonsi: I think a lot of people might think, "If someone took my child and I was in El Salvador, I-- I'd be at the U.S. Embassy banging on the door to get my kid back." Why aren't they banging on the doors of the embassy, saying, "I want my child back?"

Lee Gelernt: One mother said to me, "I got up the courage to ask, 'Where are you taking my child?' And they said, 'Chicago.'" And she said, "I had no idea if that was a person, a place, a government agency. But I was too scared to ask a follow-up question."

One of the parents his search team found in El Salvador was this woman. Her name is Sulma and she is the mother of those two boys we met in Indiana.

The stories of separated families are rarely simple and neither is theirs. Sulma told us she first sought asylum in the U.S. in 2014 with her two daughters because they were threatened by a gang leader. But a year later, she returned to El Salvador because she says her estranged husband failed to care for her two boys and the gangs were now targeting them. Sulma decided to flee to the U.S. again, this time with Adonis and Jaime - who were 5 and 9 years old.

Sharyn Alfonsi: So, what happened when you presented yourself to the border agents?

Sulma (Translation): When I got across with the kids, they saw my file and they said I was trafficking people and those children were not mine. That the birth certificates that I showed were not originals and that I had made them up.

Sharyn Alfonsi: How long after you crossed the border were you separated from your sons?

Sulma (Translation): I spent maybe 4 hours with them.

Sharyn Alfonsi: Did you get to say goodbye?

Sulma (Translation): Yes, a little because it was close to midnight, so they were asleep when they came in to say they were taking them away.

A report filed by U.S. Customs and Border Protection supports her story. It says the family crossed legally at the bridge and Sulma told officers she was afraid to return to her country and requested asylum. But U.S. border officers took her boys from her. What Sulma had no way of knowing is that the Trump administration had already started quietly separating children from their parents at the border. The practice wouldn't become public for another five months.

Sharyn Alfonsi: When they said they were going to deport you, did you say, "I want my kids to come back with me"?

Sulma (Translation): Yes, with me. Yes, I told them and they said no and that I couldn't do anything because I had brought them and turned them into immigration.

Sulma says an immigration judge warned her if she tried to cross the border again, she'd be banned from the United States for life.

She was deported back to El Salvador on one of the jets chartered by U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement. Each flight costs U.S. taxpayers about $64,000.

Sharyn Alfonsi: When you look back on it, do you regret trying to cross the border with your boys?

Sulma (Translation): Yes, my whole life, yes all the way. That's what hurts the most, what I carry the longest in my heart, that deep regret. If I could go back, I never would have left.

Jaime and Adonis were sent to New York where they spent five months in a group home before they were ultimately sent to Indiana to live with their sister, Katherine.

She was one of the daughters Sulma brought to the U.S. seven years ago and is still waiting for her own asylum claim to be resolved.

Even though Sulma and her sons spoke constantly by phone, they somehow were lost in the system. Because of that shoddy government record-keeping within U.S. Immigration, their names didn't appear on any of the lists given to search teams. So for two years, they were separated and no one was trying to get them back together. When their file was finally discovered, it was incomplete. There was no phone number or address for Sulma or her boys in Indiana. It took the ACLU and the team in El Salvador three months to track her down through relatives and friends.

This summer, the U.S. government brought the parents of 42 of the children into the country to be reunited. Sulma was one of them. She whispered a prayer of thanks as she made her way to the arrivals area at the Indianapolis airport and into the arms of her sons, for the first time in three and a half years.

It was also the first time she'd been with her oldest daughter in six years. The first time she held her granddaughter. And the first time she could thank Jaime in person for taking care of his little brother. We heard her say again and again, "I'm sorry."

Sharyn Alfonsi: When you got off the plane, you apologized to the kids.

Sulma: Yes.

Sharyn Alfonsi: Why did you do that?

Sulma (Translation): Because I felt like it was my fault that everything had happened and so I felt guilty and when I saw him I had to ask him for forgiveness.

Sharyn Alfonsi: And what's it been like, now that you're all together?

Jaime: Amazing.

Sharyn Alfonsi: Amazing?

Jaime: Yeah.

But it's not the end of their story. When we checked in with Sulma last week, she told us she had job prospects, but could not start because she was still waiting for her work papers. Sulma's permission to stay here expires in three years.

The future is also murky for her sons. According to government statistics, less than 10% of migrant children are granted asylum. The ACLU's Lee Gelernt wants Congress to step in and give the separated families a permanent home in the United States.

Lee Gelernt: Whatever else is going on at the border, and there are a lot of challenges at the border, this is a distinct group of families who were brutalized by our government and deserve relief from our government.

Sharyn Alfonsi: You wanna see this group set aside from everything that's happening at the border right now.

Lee Gelernt: We do. There's a lot of problems at the border. And they need the Biden administration's attention. But I would hate to see the larger border issues affect how we-- deal with these families.

But startling images last month from Texas show an immigration system already overwhelmed. The U.S. has expelled more than 7,000 Haitians in the last three weeks and more migrants are on the way.

The Department of Homeland Security says it is committed to picking up the pace and reunifying more families like Sulma and her boys. Late last week, the task force told us they've identified 82 families they believe will be reunified while at least one thousand children remain separated from their parents.

Produced by Guy Campanile, Lucy Hatcher and Tony Cavin. Broadcast associate, Elizabeth Germino. Edited by Joe Schanzer.