Microsoft Windows at 25 (Already!)

When the first Windows operating system was introduced by Microsoft, Ronald Reagan was in the White House, John Hughes was introducing touching teen stereotypes in "The Breakfast Club," and a young singer named Madonna was hitting the road with "The Virgin Tour." Twenty five years later, Windows, Reagan, Hughes, and Madonna are still very much at the center of our tech, political, and pop culture discussions.

Since we are a technology site, however, let's take a moment to focus on the sheer breadth of Bill Gates' achievement with Windows and to ask: how long can this go on? Now in its seventh major version, Windows can be found on about 9 out of every 10 of the world PCs, its server version is on 70 percent of the world's servers, and, of course, Gates is the

But there are cracks in the Windows business, some self-made, some the result of too much success. As Microsoft watchers look back in amazement at the last 25 years, the old Chaucer expression "There is an end to everything" is starting to look more and more relevant to a company that for many years looked invulnerable.

Competitors like Apple that once seemed like a blip on the radar are now seeing huge growth in computer sales--computers that are not shipping with Windows. In fact, numbers from IDC

No, this is not a "sky is falling moment" for Microsoft, but it could be a defining one as it moves further from the leadership of Gates into the era of CEO Steve Ballmer: Microsoft must correct its miscues in the mobile market, and define just how it will keep customers as they move more applications to the "cloud" computing environment.

To understand why that market share number is in jeopardy over the next few years, one has to look at other challenges facing Windows as a platform. Moving 25 years of customers along to new things isn't easy, of course. Generations of old software must have some sort of upgrade path. In effect, the bigger you get, the more baggage you have to drag along. And the disappointment of Windows Vista didn't help matters.

But one of the most immediate threats is existential, the notion of what exactly is a personal computer. Is it a desktop or notebook device built around Intel's ubiquitous x86 semiconductor architecture that runs Windows software? Or is it something else? Is it a device as small as a smartphone? Or is it something more like the iPad? Or is it all of the above? Does it run on x86 or the increasingly popular ARM architecture? And how exactly does Microsoft maintain control of that heterogeneous world?

One spot where you can see some seeds of change is with Windows Phone 7, which Microsoft created to

In the case of Windows, it might just be difficult to want to make too big of a change. We have a product that was created for and continues to be steeped in a usage model that is defined by form factor. But as that idea changes, Windows has to as well. Microsoft's complete reboot of its mobile platform with Windows Phone 7 is certainly a sign that the company isn't afraid to make some big changes. The real question is how to do that with something like Windows, where one of the key attractions continues to be a large library of applications--something you don't just drop.

Therein lies another problem: with developers moving applications to the cloud, the reliance on what operating system you're using becomes less relevant. Microsoft continues to do well on the other side of the equation: licensing server software and its Windows Azure platform that powers those apps. But even so, that's only half of the solution. As a developer, do you continue to invest in a platform like Windows, or focus on the Web so that your product or service can be used from any platform?

The road to Windows 7

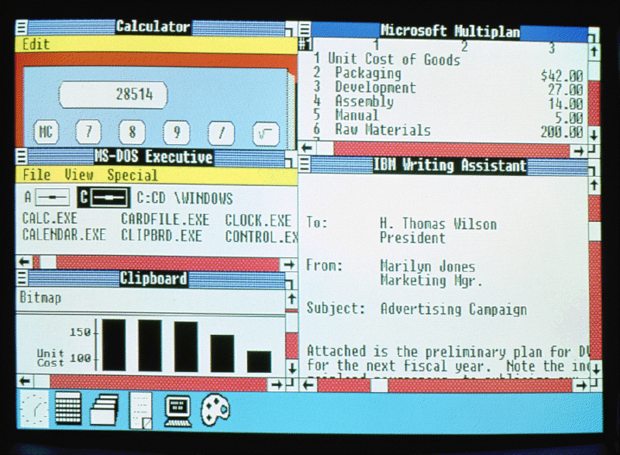

So how did we get here? On November 20, 1985, Microsoft shipped Windows 1.0 as a replacement for the DOS-prompt computing experience. The idea was that users would no longer have to remember commands to do things like browse through file directories, install programs, or simply launch programs. They could instead navigate with a keyboard and mouse. More importantly, the system brought multitasking, so users could run more than one application at a time.

While multitasking is something we now take for granted, at the time this was a killer productivity hook for computing. Even so, Windows didn't really catch on until its third iteration, some five years after the launch of the version 1.0. Windows 3's success, which can be measured in the 10 million copies it sold over two years, was based largely on the look and feel of the OS, along with backward compatibility for legacy software.

Following the Windows 3 era, the company went on to launch Windows 95, which included the start button and the task bar and a massive ad campaign featuring The Rolling Stones. This was followed by Windows 98, Windows 2000, Windows Millennium Edition, then XP--all within six years of each other. XP then lived a very successful, though what could be considered a longer than anticipated lifespan, due in large part to Windows Vista--XP's successor, which was released five years later.

Vista was met with a lukewarm reception both from consumers and companies alike, despite posting solid sales numbers. This was further complicated by Microsoft effectively conceding to device manufacturers, who were able to continue selling new computers

After Vista came Windows 7, which brings us up to now. Windows 7 has proven to be a big success for Microsoft, with the company having sold more than 240 million copies of the software since its launch last October. It's also been a faster seller than Vista, selling

Much of 7's success can be attributed to

Where does that leave us with Windows 8--or whatever Microsoft chooses to call it? Recent rumors have pegged it as having some serious virtualization prowess--enough to the point where much of the hard work that has driven the pace for the processor arms race and limited things like battery life and performance--could be done in the cloud. Such an architecture would give Microsoft and device manufacturers alike a little wiggle room to experiment with a wider variety of form factors and UI possibilities, as well as tack on new ways to deliver software and security updates. The real question then, is how to to keep that from being too jarring an experience for both developers and users alike.

Such a system may be delivered to us with that next version of Windows, but that still doesn't answer the question of the long term. What comes after that, and then again after that? And will Microsoft have the right people at the helm to guess that next step and plan ahead? The

One thing that's clear though is that Windows is a tough franchise--one that has gone through a constant cycle of refinement and re-evaluation. While it's easy to look back on some of the stumbles, it's always harder looking forward. It's also hard to argue at 25 years, with most of that being spent at the very top, that Microsoft isn't doing a lot of things right.

And who knows? Maybe one day Madonna will get tired of making new albums.

This story originally appeared on CNET