Testimony continues in hearing to determine whether Michigan school shooter gets life sentence

A teenager recalled Friday how she helped save a girl who was severely wounded during a Michigan school shooting in 2021, telling a judge that she moved her to an empty classroom, applied pressure to stop the bleeding and prayed with her.

"I asked her if she knew who God was. She said, 'Not really,'" Heidi Allen, 17, recalled.

"I think I'm supposed to be here right now," she said, describing how she felt at the time. "Because there's no other reason that I'm OK, that I'm in this hallway, completely untouched."

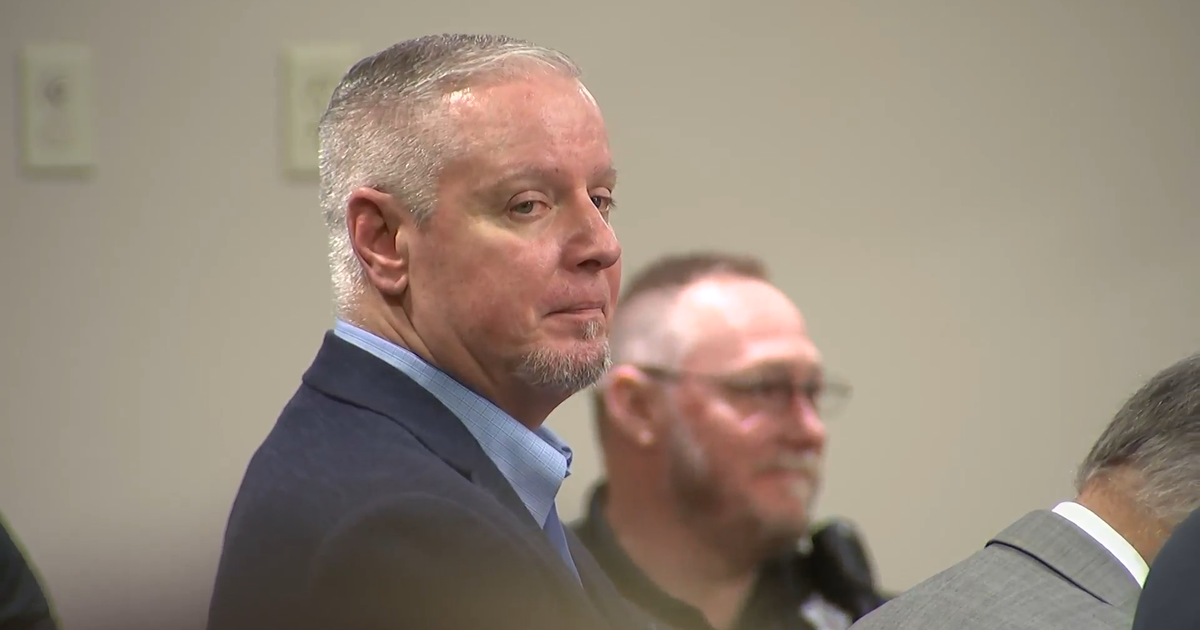

Heidi testified at a hearing to determine whether Ethan Crumbley, 17, will get a life prison sentence, or a shorter term with an opportunity for parole, for killing four students and wounding seven other people at Oxford High School.

If the shooter doesn't get a life sentence, he would be given a minimum prison sentence somewhere from 25 years to 40 years. He would then be eligible for parole, though the parole board has much discretion to keep a prisoner in custody.

Allen said she recognized him as soon as he exited a bathroom and brandished a gun.

"It fired," Allen recalled. "Everything kind of slowed down for me. It was all slow motion. I had covered my head. I dropped down. ... It sounded like a balloon popping or a locker slamming. It was very loud.

"I just prayed and covered my head," she said. "I didn't know if those were my last moments."

Allen wasn't shot, but others were. She said she took a girl into a classroom, installed a portable lock on the door and applied pressure to the girl's wounds. The victim survived.

"I just kept reassuring her she was going to be OK. She was crying," Heidi testified. "I don't fully remember what she was saying. I was trying to stay calm."

The shooter, who was 15 at the time, pleaded guilty to murder, terrorism and other crimes. But a life sentence for minors isn't automatic after a series of decisions by the U.S. Supreme Court and Michigan's top court.

Defense attorneys are arguing that he can be rehabilitated in prison and eventually released. They said the shooting followed years of a turbulent family life, grossly negligent parents and untreated mental illness.

A former warden, Ken Romanowski, testified about a variety of programs available in prison, such as mental health therapy, anger management, education and trade skills.

"Honestly, I think everybody has the potential for change. But he has to be the one who makes that choice," Romanowski said, appearing for the defense.

A psychiatrist, Dr. Fariha Qadir, said the shooter discussed having depression, hallucinations and hearing voices when they first met after his arrest. She has talked to him more than 100 times while in jail and prescribed medication for depression, mood and sleep.

James and Jennifer Crumbley are separately charged with involuntary manslaughter. They're accused of buying a gun for their son and ignoring his mental health needs.

Earlier Friday, Judge Kwame Rowe denied a request by the shooter's lawyers to stop students from testifying. They argued that it's irrelevant when applying key factors set by the U.S. Supreme Court when determining a sentence for a minor.

"I'm able to discern what's relevant to the...factors and what's not relevant," the judge said.

Prosecutors presented other witnesses Friday. An assistant principal, Kristy Gibson-Marshall, tearfully described how she tried to revive Tate Myre, a student whom she had known since he was 3 years old. He died.

"It was crushing. I had to help him," Gibson-Marshall testified. "I could feel the entrance wound in the back of his head. ... I just kept talking to him, that I love him, that I needed him to hang with me."

It took "months to get the taste of Tate's blood out of me," she said.

Gibson-Marshall also knew the shooter, who passed by but didn't harm her.

Separately, a 16-year-old boy explained how he hid in a bathroom with another student, Justin Shilling, who was killed by the shooter. Keegan Gregory said he suddenly found an opportunity to run behind the shooter's back and escape.

"I realized if I stayed I was going to die," said Keegan, who now has a tattoo to honor the victims. "I just kept running as fast as I could, making turns so if he chased me, I'd lose him."

The hearing will resume Tuesday.

There might have been opportunities to possibly prevent the shooting earlier that day. The boy and his parents met with school staff after a teacher was troubled by drawings that included a gun pointing at the words: "The thoughts won't stop. Help me."

The teen was allowed to stay in school, about 40 miles north of Detroit, though his backpack was not checked for weapons.