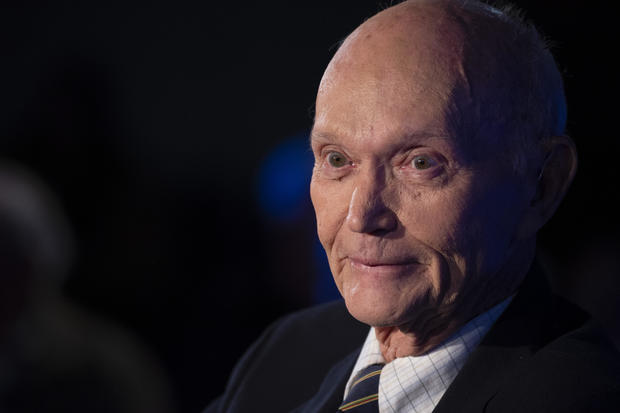

Michael Collins, Apollo 11 astronaut, has died at 90

Michael Collins, the man who stayed behind aboard the Apollo 11 command module while crewmates Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin descended to the moon and walked into history, died Wednesday after a battle with cancer, his family announced. He was 90.

"Mike always faced the challenges of life with grace and humility, and faced this, his final challenge, in the same way," his family said in a statement posted to Twitter. "We will miss him terribly. Yet we also know how lucky Mike felt to have lived the life he did. We will honor his wish for us to celebrate, not mourn, that life."

One of the most articulate astronauts to emerge in the early days of America's space program, Collins orbited the moon alone on July 20, 1969, when Armstrong and Aldrin touched down on the Sea of Tranquility, the first humans to set foot on another world.

"He may not have received equal glory, but he was an equal partner, reminding our nation about the importance of collaboration in service of great goals," President Biden said in a statement. "From his vantage point high above the Earth, he reminded us of the fragility of our own planet, and called on us to care for it like the treasure it is."

"Today the nation lost a true pioneer and lifelong advocate for exploration in astronaut Michael Collins," acting NASA Administrator Steve Jurczyk said. "As pilot of the Apollo 11 command module – some called him 'the loneliest man in history' – while his colleagues walked on the Moon for the first time, he helped our nation achieve a defining milestone. He also distinguished himself in the Gemini Program and as an Air Force pilot.

"Michael remained a tireless promoter of space. 'Exploration is not a choice, really, it's an imperative,' he said. Intensely thoughtful about his experience in orbit, he added, 'What would be worth recording is what kind of civilization we Earthlings created and whether or not we ventured out into other parts of the galaxy.'"

Collins was very candid about the technical challenges the crew faced, saying their lives depended on a long "daisy chain" of events that all had to work perfectly for the astronauts to make it home alive.

"The daisy chain, that's what worried me," he said in an interview with CBS News on the eve of the 50th anniversary of the Apollo 11 launch. "The idea that in order to have a successful moon landing, you had to have a series of relatively minor events, each one of which was successful. If one of 'em was unsuccessful, the whole scheme went down the drain."

Near the top of the list, perhaps, was the single engine that had to fire successfully to propel Armstrong and Aldrin from the lunar surface back to Collins in the Apollo command module. If that engine failed, Collins knew, he would have to return to Earth alone, leaving his friends behind.

"The lunar module ascent engine, that was it," he said. "It was a singular thing. There was one combustion chamber. It was not duplicated. That engine had to work perfectly. If it would fail to start for some reason, that was the end of them, they were dead, I was going home by myself. Those were the things that worried me."

But the mission was a resounding success, the first of six lunar landings signaling the end of the Cold War space race. While Armstrong and Aldrin got the credit for the first moon landing, Collins said he had no regrets about the role he played. He was thankful to have had it.

"Did I have the best seat on Apollo 11? No, but I was absolutely thrilled to have the seat that I did have," he said in the CBS interview. "It was a culmination of John F. Kennedy's mandate. And I was proud to be a part of that."

Andrew Chaikin, author of "A Man On the Moon: Voyages of the Apollo Astronauts," described Collins as "a delightful guy, just a pleasure to talk to, a great dry wit and of course the soul of a writer."

"He was clearly the best writer among the (astronauts), wrote the best book by an astronaut and had a bit of the poet in him," Chaikin said in an interview. "Very perceptive, very keen insights, a very balanced view of life. He did not enjoy fame at all. That wasn't what he was in this for."

With Collins' passing, Aldrin is the lone remaining member of NASA's most famous crew. Armstrong died on August 25, 2012.

The son of a career military officer, Collins was born October 31, 1930, in Rome, Italy. Following his father and older brother, he graduated from the U.S. Military Academy at West Point in 1952.

He subsequently joined the Air Force and went on to become a jet pilot, serving in various capacities until his admission to the fabled Air Force test pilot school at Edwards Air Force Base in 1960. Classmates included future astronauts Frank Borman, Jim Irwin and Tom Stafford.

After marveling at John Glenn's flight to orbit in a Mercury capsule in 1962, Collins applied to NASA to become an astronaut, only to be rejected. He applied again in 1963, and this time, he was accepted.

On July 18, 1966, Collins and commander John Young, who would later walk on the moon and command the first space shuttle mission, blasted off from Cape Canaveral in Florida in a cramped Gemini capsule atop a Titan rocket booster for the most complex space flight to date for the budding American space program.

Among the mission's accomplishments were the dual rendezvous with two Agena target satellites and a then world-record altitude of 475 miles. Collins also walked in space twice to become the third American astronaut to venture outside his spacecraft.

"My first impression (was) a feeling of awe at the wide visual field, a sense of release after the narrow restrictions of the tiny Gemini window," Collins wrote. "My God, the stars are everywhere.

"We are gliding across the world in total silence, with absolute smoothness; a motion of stately grace which makes me feel God-like as I stand erect in my sideways chariot, cruising the night sky."

Collins resigned from NASA shortly after the Apollo 11 mission and took a position at the State Department. But after little more than a year he left to become director of the Smithsonian Institution's new Air and Space Museum in Washington. After a stint in private industry, he retired to private life in 1985.

"I didn't find God on the moon, nor has my life changed dramatically in any other basic way," he wrote in "Carrying the Fire." "But although I may feel I am the same person, I also feel that I am different from other people. I have been places and done things you simply would not believe.

"I have seen the sun's true light, unfiltered by any planet's atmosphere. I have seen the ultimate black of infinity in a stillness undisturbed by any living thing. I have been pierced by cosmic rays on their endless journey from God's place to the limits of the universe, perhaps there to circle back on themselves and on my descendants."

Collins "really kept out of the limelight," Chaikin said. "People used to talk about Neil as a recluse, which he wasn't. Neil just rationed himself. ... Mike was even moreso. In many ways, Mike was even more averse to that kind of attention than Neil was and has in the last many years led a fairly quiet life, painting. He's quite a good artist, actually."

In the Air and Space Museum, the Apollo 11 command module sits on display, a monument to one of the nation's greatest triumphs. On the wall of the spacecraft's lower equipment bay, Collins had scribbled: "Spacecraft 107, alias Apollo 11, alias Columbia. The best ship to come down the line. God Bless Her. Michael Collins, CMP."

"We are a nation of explorers," he told reporters before the 20th anniversary of his flight. "We started on the East Coast, we went to the West Coast and then vertically. Starting with the Wright brothers, (Chuck) Yeager through the sound barrier, Armstrong and Aldrin on the moon, it's in our tradition, it's in our culture.

"It's a fundamental thing to want to go, to touch, to see, to smell, to learn and that, I think, will continue in the future."

Alex Sundby contributed reporting.