NASA begins search for ancient life on Mars after arrival of Perseverance, Ingenuity spacecrafts

It's been a year since the tiny helicopter Ingenuity and the one-ton rover Perseverance left planet Earth, and they've come a very long way since then. In February, they landed in a hazardous and previously unexplored part of Mars called the Jezero Crater, where Perseverance will be looking for signs of ancient life. In April, Ingenuity disconnected from Perseverance's belly and made history -- performing the first flights ever in the atmosphere of another planet. It's hard to imagine, but worth remembering as you watch this story we first broadcast in May, that this all happened millions of miles away, in outer space.

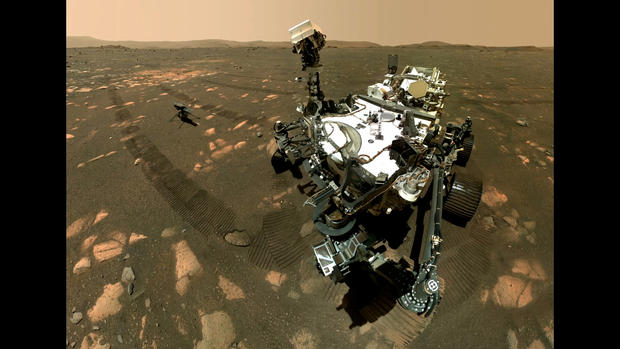

On April 6, in this desolate Martian crater, 170 million miles from Earth, Perseverance posed for a selfie with Ingenuity, the little helicopter it had just dropped off. Two weeks later, the rover's cameras recorded Ingenuity's historic first flight, hovering ten feet off the ground for 30 seconds. It may not look like much, but for those who'd worked so long to make it happen it was a reason to rejoice.

Project manager Mimi Aung led the team at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in California that's been working on Ingenuity for six years.

Anderson Cooper: How hard is it to fly a helicopter on Mars?

Mimi Aung: Very, very, very (LAUGHTER) hard. We really-- truly started with the question of, "Is it possible?"

Anderson Cooper: A lot of people thought it-- it could not be done?

Mimi Aung: Because it's really counter-intuitive. I mean, you need atmosphere for the blades to push atmosphere to get lift. And the--

Anderson Cooper: The atmosphere on Mars is completely different

Mimi Aung: The atmosphere--on Mars is so thin. I mean, the room we're in, right, it's-- compared to that, it was 1% of the atmospheric density over there. So, the question of, really, can you generate enough lift, you know, to really build-- to lift up anything, that was the fundamental question.

In subsequent flights, Ingenuity has gone higher and farther, traveling more than a mile in all, over the surface of Mars. It is a triumph not only for NASA but for its partners in the private sector who helped make various parts of the helicopter.

Matt Keennon has a history of making unusual things that can fly. He's an engineer at a company called AeroVironment, which produces drones for military and civilian use.

Anderson Cooper: I mean that's incredible.

Ten years ago, for a military research project, Keennon and his team created this robotic hummingbird, which has a tiny camera onboard.

Anderson Cooper: Whoa (LAUGH)

Matt Keennon: There it is.

Anderson Cooper: Oh, my God. That's amazing.

Keennon and engineer Ben Pipenberg led the aerovironment team that created Ingenuity's rotors, motors, and landing gear.

Anderson Cooper: Why was this so challenging?

Ben Pipenberg: Because it has to be a spacecraft as well as an aircraft. And-- and flying it as a-- as an aircraft on Mars is pretty challenging because of the density of the air. It's similar to about Earth at 100,000 feet.

Anderson Cooper: How do you go about it?

Ben Pipenberg: Well, so building everything extremely lightweight is-- really, really critical.

The helicopter's blades, for example, are made of a styrofoam-like material coated with carbon fiber.

They're stiff and strong.

Ben Pipenberg: You get a sense of how lightweight and stiff that is.

Anderson Cooper: It weighs nothing.

Ben Pipenberg: Yeah, it weighs nothing.

…but incredibly light.

Matt Keennon: Here we go, taking off.

This is the first time they've shown an outsider this version of Ingenuity, which they plan to use for education and research. They call it "Terry."

Here on Earth, Terry's blades are spinning at about 400 revolutions per minute. On Mars, in the thin atmosphere, they'd have to spin six times faster to generate the same lift.

Ingenuity cost $85 million dollars to build and operate, "Terry" a lot less. But it's still nerve-wracking to be handed its controls.

Matt Keennon: All right, go ahead. You've got it. Slide it right. You can push it all the way to the right if you want. Slide left.

Anderson Cooper: Wow.

Matt Keennon: I'll bring it up a little bit. Now stop.

The joysticks we used to fly Terry are of no use on Mars. Radio signals take too long to get there.

Even someone as good at flying drones -- and hummingbirds -- as Matt Keennon couldn't fly a helicopter on Mars. Here's what happened in 2014 in a test chamber that replicated the atmosphere on Mars when Keennon tried to use a joystick to fly an early version of Ingenuity.

Mimi Aung: Surprise.

Anderson Cooper: Wow. (LAUGH) So much for that vehicle…

Anderson Cooper: So, this very quick demonstration must have showed you a human being can't respond quickly enough to control it.

Mimi Aung: Exactly.

So engineers at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory equipped Ingenuity with a computerized system that allows it to stabilize itself and navigate on its own. In 2016, the new system aced the chamber test…

Mimi Aung: The blades are being commanded, you know, 400 or 500 times per second.

They proved it could fly. But Ingenuity still had to weigh under four pounds and fit in the belly of Perseverance.

And it had to be tough enough to survive the journey to Mars.

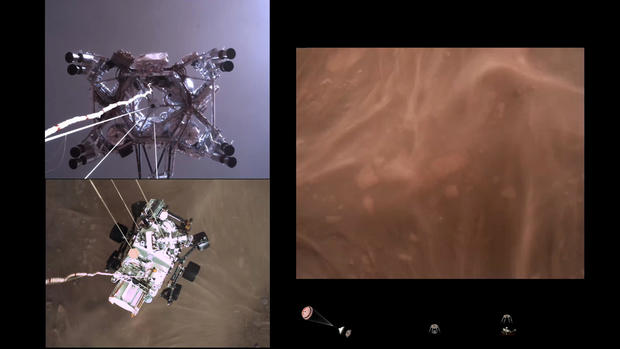

On July 30, 2020, Perseverance and Ingenuity took off from Cape Canaveral.

Nearly seven months later, as this simulation shows, the spacecraft's heat shield hit the Martian atmosphere going 12,000 miles per hour.

As he sat in the control room, Al Chen, the leader of the landing team, had absolutely no control. Radio signals would take about 11 minutes to travel from Earth to Mars. The spacecraft was pre-programmed to descend, maneuver, and pick a landing site on its own. All the work his colleagues hoped to do on Mars would be impossible if his part of the mission failed.

Anderson Cooper: How long have you been working on this mission?

Al Chen: Coming up on nine years, or so.

Anderson Cooper: Really? That's a lot of work for seven minutes of--

Al Chen: Yep. Nine--

Anderson Cooper: --terror.

Al Chen: -- nine years of work, seven minutes of terror. (LAUGH)

Anderson Cooper: It's done if the parachute doesn't work.

Al Chen: That's right. You know, no one wants to be that-- the guy the drops the baton.

No landing by a spacecraft has ever been recorded as well as this one. There were six cameras capturing it all from different angles. The parachute deployed. Then the heat shield fell away like a lens cap, and Perseverance got its first look at the ground. This is not a simulation. This is what it looks like to parachute onto Mars.

Anderson Cooper: How fast is it moving at this point?

Al Chen: Yeah, we're still going about 350 miles an hour, and still slowing down

Anderson Cooper: So it looks gentle here, but in fact you're-- the-- it's falling at more than 300 miles an hour.

Al Chen: That's right. We're heading straight down at-- at near-racecar speeds.

Below lay a series of safe landing spots. But the wind was blowing the spacecraft towards more treacherous territory to the east. And Perseverance sent a message to Earth saying the thrusters it needed to slow down might not be working properly.

Anderson Cooper: So you get a reading saying the jets that are going to help it slow down and control the landing, that they're not working?

Al Chen: The stopping power.

Anderson Cooper: So what do you do?

Al Chen: There's nothing you can do, right? Everything already happened. That's the mind-bending part of this, right?

Anderson Cooper: You are sweating now, you were just talking about it.

Al Chen: Yeah, exactly, I'm right back there again. (LAUGHTER). So, ah, yeah.

To Al Chen's relief, Perseverance's computerized landing system did what it was designed to do: it found a suitable landing spot even in rocky terrain. And despite the warning, the thrusters worked. You can see them kicking up dust as they fire to slow the spacecraft down.

The descent stage known as the "skycrane" lowered Perseverance to the ground. It hovered for a moment, then flew off to crash a safe distance away.

Al Chen: And there goes the descent stage.

Anderson Cooper: Wow.

Al Chen: At that point, big sigh of relief-- you know? I almost-- collapsed over this console.

For two months after the landing on the red planet, a team of engineers, programmers and scientists here on Earth were living on Mars time. It's their job to monitor the rover's health and tell it where to go and how to search for signs of life. While Perseverance slept to conserve energy during the freezing Martian nights, the team on earth analyzed the photographs and instrument readings it had sent back. They then prepared a list of things for it to do the following morning when it woke up.

Matt Wallace: And so it's just after midnight on Mars. The vehicle's asleep.

Project manager Matt Wallace explained that a day on Mars is 40 minutes longer than on Earth. The team's schedule was constantly changing.

Anderson Cooper: So people here are-- are Mars night shift workers.

Matt Wallace: (LAUGH) Yeah, that's a good way to think of it.

Anderson Cooper: But, I mean, working night shift is tough enough. But-- this is a night shift that's constantly shifting--

Matt Wallace: Constantly moving.

Anderson Cooper: Yeah--

Matt Wallace: That's right. Yeah.

On Perseverance's fourth day on Mars, it swiveled the powerful camera on its mast and took a look around. A space enthusiast named Sean Doran put the images together, set them to music, and posted the movie on YouTube.

Even one of the top scientists on the project was moved when he saw it.

Ken Farley: I went and got a beer and watched this thing scroll by. And that… that was the moment (CLICK) when I felt like I was there.

Ken Farley leads the science team that will direct Perseverance through the Jezero Crater. It's an area that scientists have long wanted to search for signs of ancient life that may be hidden in the rocks.

Ken Farley: The oldest evidence of life on Earth is about three and a half billion years old. Those rocks were deposited in a shallow sea. This crater that you see here was a lake three and a half billion years ago. So we are looking at the same environment in the same time period on two different planets.

Anderson Cooper: And if it's determined, however long in the future, that, "No, there was not ever life," what does that mean?

Ken Farley: The place where Perseverance landed, here in Jezero Crater-- is the most habitable time period of Mars and the most habitable environment that we know about. This is-- this is as good as it gets, at least with our current understanding of what Mars has to offer. And if we don't find life here, it does make us worry that perhaps it doesn't exist anywhere.

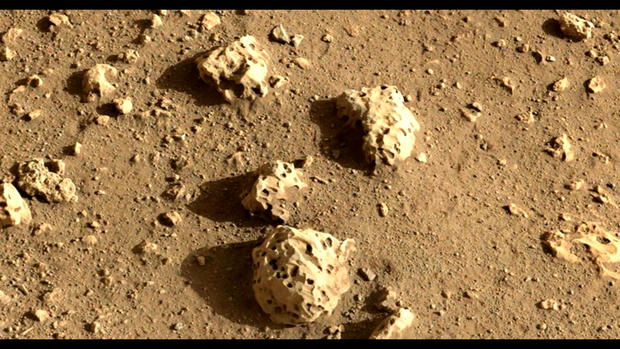

Perseverance hasn't strayed far from its landing site yet, but it's telescopic camera has already spotted a large number of boulders that Ken Farley says he didn't expect to see in the middle of an ancient lake.

Anderson Cooper: So this has surprised you.

Ken Farley: Absolutely, yeah.

Anderson Cooper: So what did those boulders tell you?

Ken Farley: The most reasonable interpretation is a flood. You don't have fast flowing water out in the middle of a lake. You get fast flowing water in a river. And so what that's telling us is: there was a river that was capable of transporting boulders that were this big.

Anderson Cooper: So what? The lake would have gone down perhaps and then later on there was a flood?

Ken Farley: Yeah. Exactly.

Perseverance was supposed to leave Ingenuity behind after a 30-day demonstration of its flying ability. But NASA officials decided to keep the duo together longer to explore how rovers and helicopters might work together in the future.

The fastest that Perseverance was designed to travel is a tenth of a mile per hour. Ingenuity has already gone 80 times faster, according to project manager Mimi Aung.

Mimi Aung: Adding an aerial vehicle, a flying vehicle for space exploration will be game changing.

Anderson Cooper: It frees you, in a way.

Mimi Aung: Absolutely, yes. So, a flying vehicle, a rotorcraft would allow us to get to places we simply can't access today, like sites of steep cliffs, you know, inside deep crevices.

After Perseverance explores the floor of Jezero Crater, it'll head towards what's believed to be the remnant of an ancient river delta, where billions of years ago conditions should have been ripe for microorganisms to exist. As this simulation shows, the rover's robotic arm can collect about 40 core samples of rock that'll be sealed in special tubes and left on the planet's surface. NASA plans to send another mission to Mars to retrieve the tubes and bring them back to Earth. In about ten years, Ken Farley says, scientists examining those samples may be confronted with a new and perplexing question.

Ken Farley: How do you look for life that may not be life as you know it? We've never had to do that before, we've never had to actually ask the question...

Anderson Cooper: "Is there a form of life that we can't even conceive of?"

Ken Farley: Yeah, we're gonna have to conceive of it. I think that's the whole point of this: We're gonna have to start conceiving of life as we don't know it.

If all goes according to plan, Perseverance will be making tracks on Mars for years to come. Since it's carrying the first working audio microphones on the red planet, we leave you with what it sounds like as the one-ton rover slowly moves across the vast, lonely expanses of Mars.

Since our story first aired, China landed its first rover on Mars – about a thousand miles away from where Perseverance is located. China's National Space Administration has said it too plans to collect samples of the Red Planet and bring them back to Earth.

Produced by Andy Court. Associate producer, Evie Salomon. Broadcast associate, Annabelle Hanflig. Edited by Richard Buddenhagen.